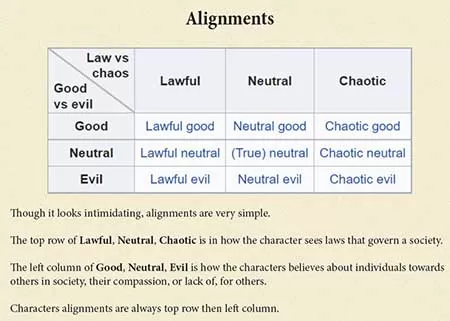

Good and evil were introduced into the game at a time when the whole concept of role-playing was much simpler. A typical campaign used to involve a dungeon full of horrible monsters and traps, and a nearby castle or town where supplies and rumors were readily available for those with the gold to buy them. Even players with cleric characters did not usually know the name or nature of the god they worshiped; they knew only that through prayer their PCs could obtain various spells to aid the party.

Motives of kings and churches were unimportant, unless they were offering bounties for particular monsters. War and politics were unknown; adventuring in dungeons was the major activity of the strong and bold, and all else revolved around adventuring. Needless to say, a character in such a campaign needed a reason to be making his living at killing things and taking their riches... . But to adventure and kill without meaning may be considered amoral.

Alignment gave characters a reason. A character could kill something with a clean conscience if he knew that it was evil and thus ready to wreak whatever havoc it possibly could on society until it was destroyed. A character whose job it was to destroy evil was quite obviously good, for he was the guardian of society.

Alignment had another benefit too: in the absence of actual laws and religious beliefs, it was nevertheless possible to tell a character when he was getting out of line. For instance, even though a certain merchant might have been a defenseless old man, and killing him might have been the cheapest way to get supplies from his shop, the players could not exploit the campaign in that way because their characters had morals to uphold.

At the most basic level of play, alignment is an indispensable part of the game. But this is not the only level of play. As they become comfortable with the idea of running characters, players begin to look deeper than the sort of clear-cut situations described above; they want to know how player-characters feel about other things, like poisoning their enemies or killing the monsters' young, and they want to know what the morals are that make the characters feel that way.

In the real world, good and evil are invented concepts. Societies label their own values as good, and those of the enemy (or the threatening or the unknown) as evil. In the simple campaign described above, this would not do; a character who makes his living by killing things wants to know that the enemy is truly evil, not just a perceived evil. So, realism had to be abandoned.

Alignment was approached in the same way that magic was handled; that is to say, as a thing common in literature and unknown in the real world. Each and every intelligent being would be motivated by some absolute cause which would be perceived by all as the same thing. Thus, a paladin not only would believe himself to be good, but would be seen as good even by his enemies.

The system that was chosen comes straight from the perceptions of the creators, and thus straight from twentieth-century America. While "life, relative freedom, and the prospect of happiness" might satisfy the typical modern gamer as being part of the framework of good, they would not satisfy most of the societies in a game universe. In fact, there is no system that could conceivably satisfy all the creatures in a gaming universe, because it is the differences in their views that put them at odds in the first place.

No one has ever decided that certain values are good, and then chosen to oppose them and be consciously evil, and there is no possible reason why any sane person ever would, even if he is just a character in a game.

No wonder the typical paladin hypocritically preaches respect for all life, while a value system he would more realistically possess, that of religious intolerance, determines his actions. Subconsciously, if not consciously, we know that a paladin is not good in the sense of the definition we have been given. But when a dilemma arises, we make the fair mistake of turning to the rules for an answer and find in retrospect that most of what our character does is wrong according to this supposedly absolute definition of good.

So where should we turn? To a new set of guidelines, invented with the paladins of the Middle Ages in mind? Unfortunately, this would not solve the problem, because it would still be based on a system of universal perceptions, where each character "knows" what good is, but some choose to turn their backs on it. A system invented for the paladin would fall apart when applied to his enemies.

If good and evil are not to be taken for granted, there must be another way for characters to choose and adhere to a system of beliefs. If there were not one readily available, the task at hand would be too enormous to even contemplate. But there is. Characters no longer worship intangible forces whose only purpose is to grant spells, and they no longer serve kings whose only purpose is to provide bounties and ransoms. The imagination of the DM can all provide gods who expect their followers to behave in a certain way. Kings and other people in positions of power also will expect certain behavior from their subjects - sometimes because of their own religious beliefs, and sometimes to promote their own selfish ends. The list of logical motivations that a character can have goes beyond that. He need not be pious or loyal to find a slot in this less absolute system, for he may well have selfish ends of his own.

The PC need never decide to be good or evil, lawful or chaotic. He will decide whether he is pacifistic or pugilistic, whether he craves or shuns material goods, whether he has a hot temper or a slow fuse, whether he is merciful or vengeful, or whatever else he thinks is important in understanding his character. (Sometimes these will be determined in part by the character's class). Unlike a traditional alignment, these guidelines need not be all saintly or all deplorable; a mix is entirely possible and will result in far more interesting and viable characters. A character need no longer be denied honesty and trustworthiness simply because he wishes to be materialistic and consider the slightest provocation an invitation to light. Also, unlike the standard alignment code, additions and changes can be made to the list whenever the player discovers the list to be incomplete in some way, or if some value turns out to be incompatible with the other ones.

Once alignment becomes a personal and tangible set of values instead of a rigid slot, characters are free to act as they truly should, in their capacity as servants to a king or a god, or in their desire to build an empire, gain a fortune, or free an enslaved people. Cause and effect are a character's motivation. If a being acts in the interests of a character or his superiors, it is a good being. If it opposes those interests, it is a bad being.

Breaking the shackles of alignment do give D&D possibilities that are endless, yet alignment gives guidance: to adventure and kill without meaning... .