Era Long Ago

In an era long forgotten, a time shrouded in mystery and wonder, there appeared a thousand curious chests, each marked with runes and symbols that spoke to ancient wisdom and hidden secrets. In the year 1974, they found their way into the homes of mortals, who, unsuspecting of the magic within, were drawn to their enigmatic presence.

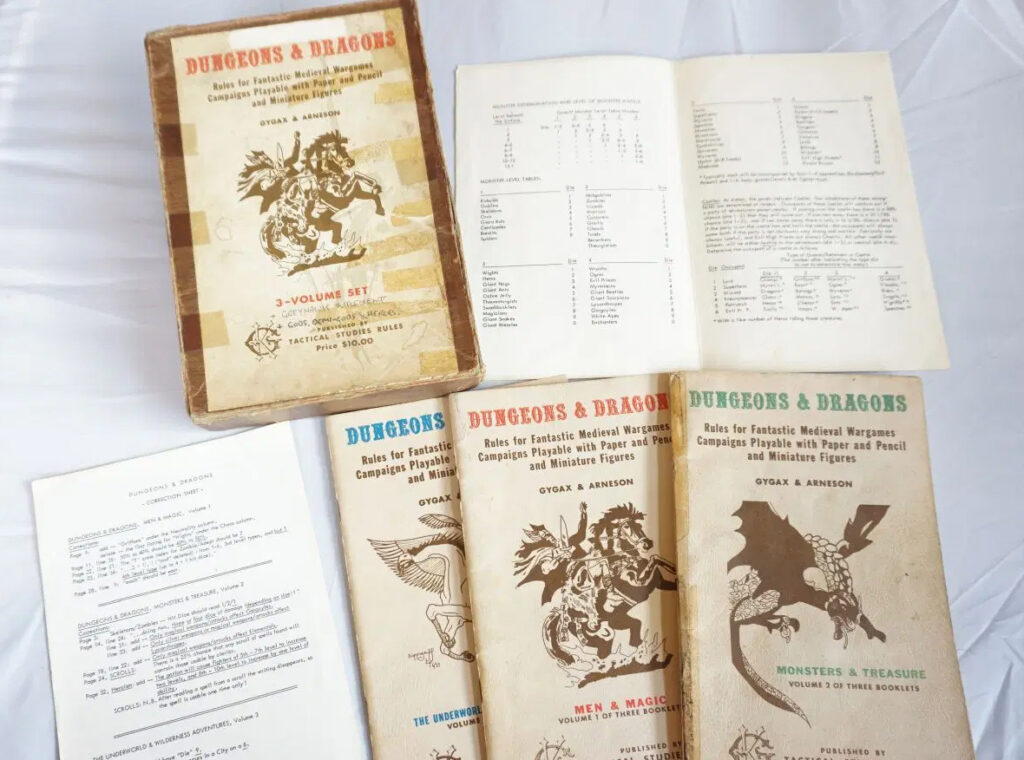

Though no discerning eye could mistake these wooden-grained boxes for the mighty treasure chests of oak spoken of in legends, within their cardboard walls lay treasures beyond mere gold and jewels. Upon lifting the lid, those who dared were met with an explosion of adventures, the promise of journeys through realms fantastic and terrifying. The legend on the cover whispered of "Rules for Fantastic Medieval Wargames Campaigns," with sacred tomes to guide the reader through the lands of Men & Magic, Monsters & Treasure, and paths unknown to Underworld & Wilderness Adventures.

The Dungeons & Dragons, as it was named, was not a mere pastime to gaze upon, like those games played on boards or seen on glowing screens. No, these three slim rulebooks held the keys to a new way of weaving fantasy into reality, a way to conjure adventures from thin air, guided only by the voice and the mind's eye.

In the days of old, a figure of power, known as the Dungeon Master, or "referee" in the common tongue, would paint with words a shared imaginary world. The players, acting as characters, would respond with actions, each attempting to outwit and challenge the other, weaving together a tapestry of tales. The magic of the game was such that it lived not in boards or pieces, but in the very hearts and minds of those who played.

Yet, if one were to peer closely at the runes on the box, they would find a hidden truth: this game could be played "with paper and pencil and miniature figures." This last element, the miniature figures, is where the visual history of this mystical game began. Through these tiny effigies, the world of Dungeons & Dragons took shape in the physical realm, and the legacy of a game that transcended time and space was born.

Tabletop Warlords

In the early dawn of the 20th century, a tale emerged from the quill of a renowned British scribe of science and wonder, H.G. Wells. His chronicle was titled "Little Wars," a book of wisdom that awakened the essence of combat and valor through the leaden figures that adorned the nurseries of his time. These were no mere children's playthings but miniature emblems of the cavalry, infantry, and artillery that shaped the world's history.

Even before Wells bestowed his enchanted rulebook upon the world, there existed circles of wise hobbyists who had already conjured dioramas to depict great wars and epic battles. Inspired by Wells's words, a fervent community of British tabletop warlords arose, their imaginations ablaze with elaborate skirmishes fought with toy soldiers. Unlike the abstract tokens pushed around segmented maps, these miniature warriors were sculpted to breathe life into the very appearance of war.

A visual spectacle it was, with scenes so vivid that they could almost be heard and felt. Determined masters of the game would craft the three-dimensional terrain of battlefields where mighty legions clashed, adorned with model trees, houses, and hills. The illusion was mesmerizing, and accuracy became the sacred pursuit, from the uniforms and weapons to the very landscape where they fought. This endeavor beckoned to retired veterans and civilized British gentlemen, for whom the reenactment of history was a serious and honorable task.

As the years marched on, the 1950s saw the wargaming craft traverse the seas and take root in the New World. Organized communities blossomed with conventions and newsletters dedicated to gaming culture. Companies like Avalon Hill bridged the past and present, enticing younger generations with games based on historic battles, from Waterloo to D-Day.

By the time the 1970s approached, the world of miniature wargaming expanded into realms of castles and armored knights, foot soldiers, and medieval weaponry. This plethora of fantastical material beckoned the birth of printed medieval wargaming rules.

Answering this mystical calling was a Midwestern sorcerer of games named Gary Gygax. A fanatical wargamer, he championed the scene in his hometown of Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. In 1968, he summoned a gathering of nearly one hundred fellow gaming enthusiasts, a convention that would become known as "Gen Con." It was here that Gygax discovered the Siege of Bodenburg, igniting a passion for medieval wargaming that would lead him to remark, "There is a great interest in wargames of ancient and medieval times but few games are published."

Chainmail Collaboration

Within two years, he founded the Lake Geneva Tactical Studies Association (LGTSA) and, not long after, the Castle & Crusade Society, both dedicated to the art and perfection of wargaming rules for the Middle Ages. Alongside Jeff Perren, a fellow LGTSA member, Gygax crafted rules for infantry and cavalry combat, delving into the wisdom of historians and drawing heavily from ancient sources.

Thus, in collaboration and dedication, Gygax's passion wove the fabric of a new era in gaming. With a heart afire with the love of wargames and driven by a connection to a community of enthusiasts, Gygax's efforts laid the groundwork for a realm of imagination, strategy, and history. His endeavor was not one for riches but one for the soul, a testament to the unending human desire to explore, create, and connect through the magical realm of games.

In an age of valor and might, when steel and cunning ruled the battlefield, the wargaming sorcerers Perren and Gygax sought to bring life to their craft. To breathe vision into their conflicts, they turned to the celebrated artist and chronicler, Jack Coggins, master of illustrating history's greatest warriors.

Coggins's tome, "The Fighting Man: An Illustrated History of the World's Greatest Fighting Forces," bore the image of a mounted crusader, frozen in time as his sword swung toward foot soldiers bracing with shields and spears. Through the masterful strokes of Coggins's brush, the question, "What did it look like?" was answered, casting a vivid spell that captured the very essence of battle.

Inspired by the magic held within the pages of Coggins's work, Perren and Gygax each wielded their quills to recreate the scene. Their illustrations appeared in the Castle & Crusade Society's mystical scroll known as the "Domesday Book," reaching but a few devotees of their craft.

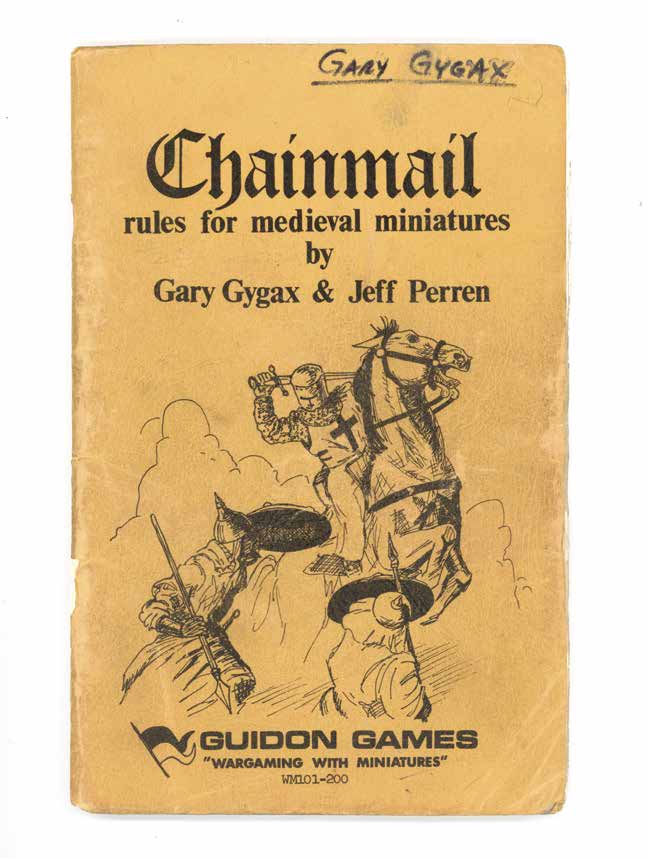

In the year that followed, fate brought them to the path of Don Lowry, a merchant of games who sought to challenge the monolithic rule of Avalon Hill. Lowry, in his hidden realm of rural Evansville, Indiana, established Guidon Games, an imprint to share the art of war. Seeing promise in the medieval rules forged by Perren and Gygax, Lowry embraced the duo's creation under the banner of "Chainmail." This treasure was offered to the world for a mere two gold coins and bore upon its cover Lowry's rendition of Coggins's mounted knight.

In those days, the realms of wargaming and artistry were akin to a brotherhood, where close imitations were shared and celebrated. They were as the "swipes" among the comic book minstrels, who would take inspiration from the panels of renowned illustrators like Jack Kirby, adding their essence to their homebrewed tales.

Lowry's homage to Coggins's battle scene, thus, became a relic, a symbol of a new dawn in the world of fantasy and gaming. It was more than an image; it was a spark that ignited the imagination of many, a precursor to the legendary Dungeons & Dragons, whose rulebooks would later intertwine with the very fabric of Chainmail.

Such was the genesis of an art that transcended mere ink and paper, blossoming into a world of magic and wonder that continues to enchant the hearts of those who dare to dream, to battle, and to adventure in the realms of the fantastical.

In the realm of wargamers, a time was upon them when historical accuracy and detailed craftsmanship were heralded as the highest virtues. Miniature knights clashed with swords, their armor meticulously crafted, their battlefield tactics derived from the annals of history.

But a restless creative spirit stirred within Gary Gygax, a devotee not just to history but to the realms of fantasy fiction. Fueled by his passion for the mystical and magical, he envisioned an extraordinary new expansion to the medieval rules of wargaming.

This enchanting creation, known as the "Fantasy Supplement," formed the final third of the Chainmail booklet, and it was nothing short of revolutionary. Gone were the strictures of historical accuracy, replaced by a fantastical realm filled with goblins, trolls, giants, dragons, heroes, and wizards drawn from the rich tapestry of sword-and-sorcery literature.

With Jeff Perren as his co-creator, Gygax invited wargamers to forge new legends, whether they sought to recreate the epic struggles penned by J.R.R. Tolkien and Robert E. Howard or invent new worlds of their own design. Battles like Helm's Deep from the Lord of the Rings were now possible, with orcs, elves, and dwarves clashing in a grand spectacle.

The fantastic supplement brought a unique challenge, however. How were these mythical creatures to be depicted in miniature form? Tolkien and others offered but cryptic descriptions. The elusive nature of the Balrog served as a notorious example, described only as "like a great shadow."

With no ready-made figures available, creativity flourished within Gygax's gaming circle in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. Utilizing 40-millimeter Elastolin figures, smaller archers and Turks, and even 54-millimeter plastic Native American figures, they painted and repurposed existing toys. Giants were crafted from 70-millimeter figures, with heads adorned with hair snipped from the dolls of Gygax's unsuspecting daughters. Dragons were born from plastic dinosaurs, and a giant sloth was transformed into a Balrog.

Gygax, having lost his insurance job, dedicated his time to these endeavors, even as he worked odd jobs to make ends meet. The scarcity of means did not dampen the creativity, as Gygax shared his inventive ways with fellow enthusiasts, encouraging toy makers to rise to the challenge of creating properly-scaled fantasy figures.

This fantastical shift in wargaming marked a profound evolution in the hobby, blurring the lines between history and imagination. It was a testament to the boundless creativity and innovation of a community, willing to transcend convention and embrace the uncharted realms of fantasy.

The legacy of Gygax's "Fantasy Supplement" in Chainmail stands not merely as an expansion of a game but as a celebration of artistic creativity, a love letter to fantasy literature, and a call to all adventurers to seize their quills and brushes, breathe life into the unreal, and embark on grand campaigns into the unknown.

Blackmoor and Castle Greyhawk

In the early days of role-playing games, a convergence of imagination, creativity, and passion gave birth to a world that would forever transform the landscape of gaming. Among the pioneers was an imaginative college history major from St. Paul, Minnesota, named Dave Arneson.

Arneson, who shared Gary Gygax's love for figure casting and the fantasy genre, was one of the first to embrace Chainmail in 1971. He was part of an energetic college gaming club, and together they joined Gygax's Castle & Crusade Society, participating in the development of an ambitious imaginary realm known as the Great Kingdom.

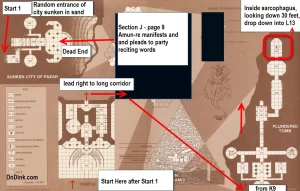

The Great Kingdom was not just a setting; it was a collaborative world-building project. Different parts were developed and shared through correspondence. Among the lands, a marshy northern region known as Blackmoor caught attention. It was Arneson's personal creation, anchored by a great and ancient castle, Castle Blackmoor.

But Arneson's imagination didn't stop at the surface. Beneath Castle Blackmoor, he crafted a dungeon teeming with strange and perilous creatures. Small groups of adventurers, controlled by individual players, would explore this underworld, facing horrors orchestrated by a "referee," usually Arneson himself.

This was more than just a game of battle and conquest; it was an "open sandbox" experience. Arneson introduced new classes like the priestly (cleric) type and the notion of adventurers leveling up. He shared this through his fanzine, Corner of the Table, and the Castle & Crusade Society's Domesday Book.

Gygax, a fellow admirer of pulp fantasy, recognized the brilliance in Arneson's creation. Here was an opportunity not just to play a game but to become the heroes of their own fantasy. Inspired, Gygax began developing his own dungeon beneath Castle Greyhawk in the southern part of the Great Kingdom.

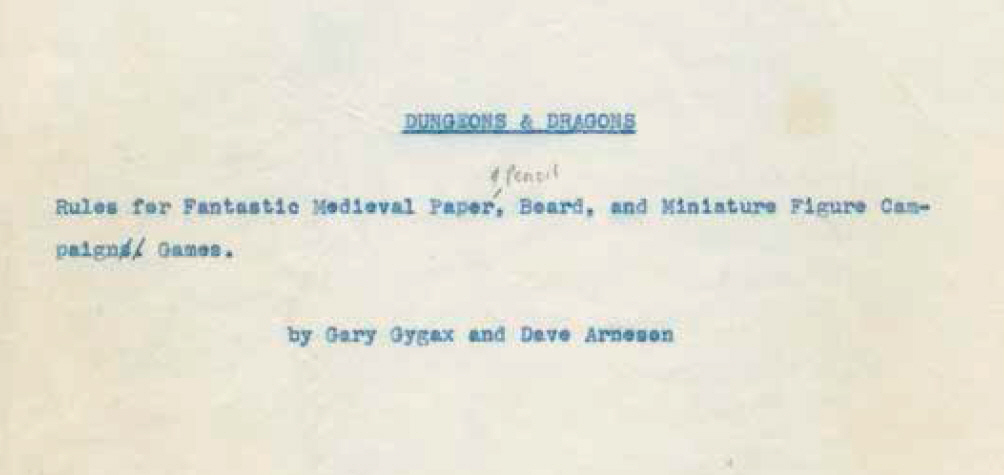

What began as shared enthusiasm soon evolved into private correspondence and collaboration between Gygax and Arneson. They took their ideas, innovations, and unbounded creativity and started crafting a draft for what would soon be known as Dungeons & Dragons.

The synthesis of Gygax's rules and structure with Arneson's creativity and open-ended gameplay marked a seismic shift in the world of gaming. Dungeons & Dragons became more than just a game; it was a vehicle for storytelling, creativity, and shared adventure.

The legacy of these early days, of Blackmoor and Castle Greyhawk, is etched into the annals of gaming history. It's a testament to the power of imagination and collaboration, to the magic that happens when creative minds come together to forge new worlds. Dungeons & Dragons was not just a game; it was, and remains, a phenomenon that opened the door to infinite realms of possibility.

The collaboration between Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson on Dungeons & Dragons marked a pivotal moment in the world of tabletop gaming. Their endeavor was just getting off the ground when it caught the attention of a prominent miniature firm, signaling a new era in visualizing fantasy creatures.

Jack Scruby, one of the fathers of American miniature wargaming based in California, planned to create his own fantasy figures that could be used with games like Chainmail. He reached out to Guidon Games, the publisher of Chainmail, and this opened a unique opportunity for Gygax to provide input on how creatures from Tolkien and other fantasy sources should appear.

In a letter to Scruby dated May 1973, Gygax foreshadowed the development of Dungeons & Dragons by mentioning that he and Arneson were working on a "campaign rule booklet" that would tie into Chainmail. This booklet, he promised, would be filled with "an entire phantasmagoria of weird critters" and would be the first time art was developed specifically for Dungeons & Dragons.

Gygax himself admitted that his skills as a draftsman might not be up to the task, but he had hope in a talented associate within the Lake Geneva Tactical Studies Association (LGTSA). He revealed that the spouse of one of his associates might provide illustrations for the booklets, even promising to provide Scruby with some quick sketches she had made.

This early interaction with Scruby not only highlighted the collaborative and innovative spirit of the time but also emphasized the importance of visual representation in bringing the fantastical world of Dungeons & Dragons to life. The art and illustrations would become a vital part of the game's identity, offering players a glimpse into the mysterious and magical realms they were exploring.

The creation of fantasy miniatures and the development of unique illustrations specifically for the game underscored the evolution of the genre. It was no longer just about rules and mechanics; it was about creating a visually immersive experience that allowed players to see, as well as imagine, the extraordinary creatures and landscapes of their adventures.

Artistic Flair

Dungeons & Dragons was becoming more than a game; it was shaping into a rich and textured universe, where creativity, storytelling, and artistry were interwoven. The partnership with Scruby and the commitment to visual art were symbolic of a broader shift, where the fantastical was not just described in words but depicted in images, engaging players in a more profound and multidimensional way.

In the bustling hub of the gaming community, the talented local artist Cookie Corey - known to many as the partner of wargaming enthusiast Bill Corey - became the talk of the town. Bill, a member of the LGTSA, was well-known for being the transport lifeline for the driver's license-less Gygax. Cookie Corey's "fast sketches" caught Gygax's eye, two of which even adorned the legendary pages of Dungeons & Dragons books, leaving one to remain a mystery, unpublished.

Gygax was enchanted by Corey's artistic flair and hoped to see a series of illustrations for his forthcoming game spring to life under Corey's hand. However, as time ticked on and the project morphed, the door opened for other artists to leave their mark on the fantastical world of D&D.

Guidon Games, the initial imprint under which Gygax planned to unveil D&D, found itself scraping the barrel with a lean art budget. A desperate cry for creative contributions rang out, but alas, free work was a rare gem. Gygax's quest for artistic assistance led him to an unlikely ally - his wife Mary's half-sister, Keenan Powell.

With the excitement of recent graduation, the allure of fantasy literature, and an untrained yet promising knack for illustration, Powell journeyed to the Gygax family home at 330 Center Street. This quaint, tiny white house, teetering on the brink of overflow with seven family members and a bulky shoe-cobbling machine in the basement, became the crucible of creativity for Dungeons & Dragons.

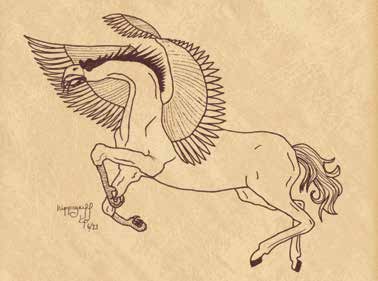

Over a magical summer between June and August of 1973, Powell crafted a dozen mesmerizing illustrations, capturing the essence of creatures like the majestic pegasus and the enigmatic medusa. Her work lent life to the game, breathing existence into imaginary beasts by drawing inspiration from real-world creatures.

However, this artistic journey was not without its trials. Like Corey's sketches, Powell's pencil drawings needed to be traced in pen, giving them a thin, ethereal quality in print.

With the artwork sent from the sunny landscapes of California, reality struck. Guidon Games was floundering financially, and the dream of publishing this bold new game hung in the balance. For Gygax, the crossroads were clear: To make Dungeons & Dragons a reality, he would have to forge his own path, starting a company from scratch.

Driven by pure passion, time, and an abundance of creative ideas but no money, Gygax turned to his trusted friend, Don Kaye of the LGTSA. With a daring loan of $1,000, they birthed their imprint, Tactical Studies Rules (TSR), a symbolic extension of their childhood adventures around Lake Geneva. It was an entity born not just for business, but a club, a community - a manifestation of dreams.

Their first venture, a miniature wargame based on the English Civil War called Cavaliers and Roundheads, marked the beginning of an era. It was the precursor to what would eventually become the beloved Dungeons & Dragons, and the start of a fantastical journey that resonated with a generation. The very first product to bear the unique "GK" logo of TSR had arrived, a mark that would become synonymous with creativity, imagination, and adventure.

In the burgeoning world of Tactical Studies Rules (TSR), a beacon of creativity emerged from the heartland of Rockford, Illinois. A young, teenage wargamer named Greg Bell, with a natural flair for artistic expression, was drawn into the exciting collaboration with the gaming legends Jeff Perren and Gygax.

TSR Staff Artist

Bell's world extended beyond the bounds of Rockford as he braved the fifty-five-mile journey to the gaming haven of Lake Geneva. A member of the illustrious Castle & Crusade Society, his style was both enigmatic and robust, comprised of bold shapes and lines. In a surprising alchemy of creativity and raw talent, Bell's art transcended the limitations of the crude printing process that TSR's budget constraints imposed.

Rising beyond mere artistic contribution, Bell became TSR's inaugural staff artist, embodying the visual spirit of the company's first four wargame releases. His strokes painted the realms of Dungeons & Dragons, his hand contributing around two dozen mesmerizing illustrations. Leftovers from his prolific output even adorned the first Dungeons & Dragons supplement.

The clock ticked relentlessly towards the end of 1973. Gygax's plans for the game's artistic tapestry changed and morphed, time and again. Working late into the publication process, Bell's collaboration with Gygax was often a frantic, mail-driven dialogue. The words "Can you whip up something real quick?" echoed from Gygax's lips, often sending Bell into an eleventh-hour creative frenzy.

One can imagine the panic of December 27, 1973, when Gygax's letter to Arneson reveals his worry: "the cover art isn't in from Bell, and we cannot roll without some." Dungeons & Dragons' fate teetered on Bell's shoulders, production stalling as everyone awaited his final masterpiece.

The creative journey was a battlefield strewn with challenges, not least of which was Bell's mission to breathe life into fantastic creatures unseen and unimaginable on paper. Time was a relentless enemy, and confusion often reigned. Questions like "Okay, what is this thing?" became a daily struggle as Bell traversed unknown territories.

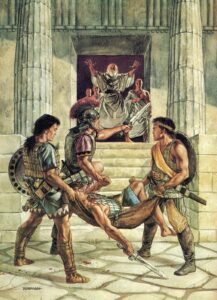

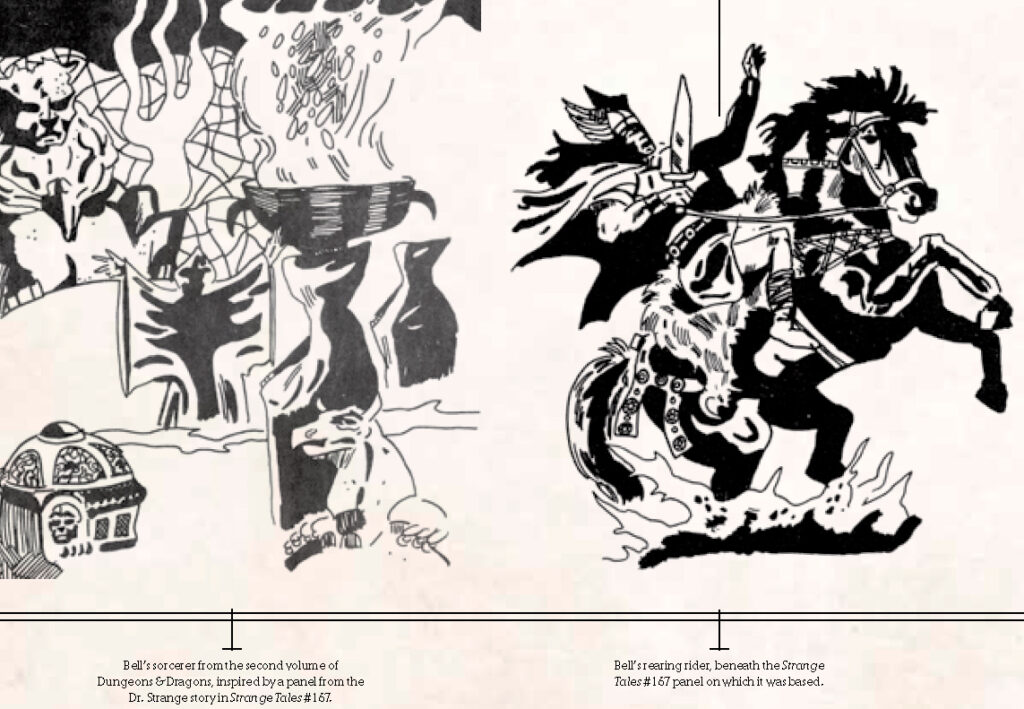

Turning to the familiar and established world of comic books, Bell found his muse. Marvel's Strange Tales #167, published in April 1968, became a rich canvas of inspiration for Bell's early art in Dungeons and Dragons. His work channeled the mystical and adventurous tales within, from a rearing rider echoing the Dr. Strange story, "This Dream . . . This Doom!" to other elements drawn from the fantastic journeys of Nick Fury.

Bell's art for Dungeons & Dragons wasn't merely illustrations; it was the transformation of existing themes into something uniquely TSR. His work painted the tales of sorcerers and barbarians, swordsmen who defiantly raised their blades to the words "Fight On!" Bell's contributions were the echo of a bygone era, yet they pulsed with a new heartbeat, becoming the heralding visuals of a game that would captivate generations to come.

In the whirlwind creation of Dungeons & Dragons, the artistic collaboration extended beyond Bell's visionary illustrations. Mid-January saw co-creator Dave Arneson joining the creative tide, dispatching his own captivating contributions, alongside drawings from the enigmatic Twin Cities circle.

Gygax was greeted by a potpourri of imagination. Arneson's "worm" wriggled its way into history as the very first depiction of the now-iconic purple worm, forever immortalized in the annals of Dungeons & Dragons lore. A mysterious, unattributed print showed a majestic dragon, half-submerged, emerging from the water-christened by Gygax as the "Head of a Dragon Turtle."

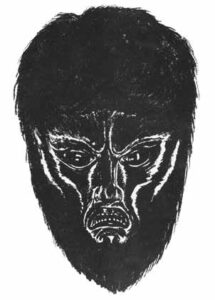

Joining these artistic forces were the contributions of Corey, Powell, and a poignant piece from Gygax's childhood friend, Tom Keogh. Keogh, who had aspired to be an artist but died young, had once shared Gygax's love for the macabre and fantastical. A drawing of a werewolf's face from his hand would find a place in the game, a silent tribute in memoriam.

In Retrospect

It's easy, in retrospect, to dismiss the art of the original Dungeons & Dragons as amateurish or crude. But the truth is richer, woven from the threads of youthful enthusiasm and camaraderie. These were not trained artists but high-school-aged "doodlers," offering their skills as a favor to Gygax. Their efforts couldn't be measured against the standards of professional artists; they were the beating heart of a budding dream.

The art budget, a mere one hundred dollars, told a tale of passion over commerce. A monster portrait could earn an artist two dollars, while a more complex scene might fetch three. With a total printing budget scarcely over two thousand dollars-later exceeded by nearly half-Gygax and his team had to navigate cost controls with ingenuity and spirit.

The financial intricacies reached beyond the art. Royalties of two to three dollars for every additional thousand copies printed might have seemed a small sum, but Gygax's groaning letter to Arneson, lamenting the "beans" shelled out to some "grubby artist," revealed the tightrope they walked. Yet, the art's primitive charm became an accessible gateway, inviting players to visualize the fantastic in games.

The path to realization took unexpected turns. When the budget spiraled, salvation appeared in the form of Brian Blume. A newcomer to Gygax's local gaming group, Blume's northern Illinois home in Wauconda was a familiar departure point for adventures in Lake Geneva. An apprentice toolmaker, he became an unwitting hero, his cash infusion vital to the financial survival of the project.

Blume's earnest investment was more than monetary; his presence often graced Gygax's couch after nights filled with hacking, slashing, and endless questing. When he learned of his gaming companions' financial straits, he leaped into action. Times being what they were, Gygax and Kaye welcomed Blume into the TSR partnership, his help transforming Dungeons & Dragons from a dream into tangible reality.

Together, the three partners took charge, assembling and selling those first thousand copies. Their collaboration was a symphony of imagination, resourcefulness, and an unwavering belief in a vision that transcended art and gaming. It was the birth of a cultural phenomenon, born from the hands and hearts of a dedicated few, who dared to conjure the fantastic from the ordinary, forever altering the landscape of entertainment.