In the twisted alleys of goblin society, a chaotic dance plays out. These wretched creatures, small and sly, band together not out of loyalty but from the fear of mightier beings. They're manipulators, opportunists, and bullies, thriving in a brutal hierarchy led by the strongest-or the craftiest.

Though weak on their own, goblins master the dark arts of deception and psychological warfare, earning ranks with lies and threats. They savor cruelty not just among themselves but extend it to prisoners, subjecting them to unimaginable torture. It's not uncommon to find blind ogres or trolls driven to frenzied warfare by their goblin captors.

Small in stature but grand in malice, goblins rarely exceed four feet. Males are thin and have growing ears-a tale of their age-while females grow in girth when well-fed. After a gestation of five months, they birth large litters that grow rapidly, though their infancy is harsh, marked by neglect.

Their varied forms adapt to their surroundings: the stealthy forest goblins, the militant hill goblins, and the twisted cave dwellers. Their harsh language of clicks and hard consonants gives names like Azkak and Zimkrik. Comfort in darkness and a natural distaste for open spaces define them.

Forest goblins are the most mystical, living in balance with nature yet altering their territory with crude traps. Clad in makeshift armor and wielding bows and spears, they wage relentless guerrilla warfare against elves. They fear, worship, and dread thousands of things, constantly creating new gods from angry clouds to oddly shaped trees.

About three-and-a-half feet tall and orange-tanned, hill goblins are known to most. They're equipped with looted armor and crafty weapons and take inspiration from hobgoblins in organization. They entertain themselves with captive wolves and exotic beasts, pitting them against each other in bloody fights.

In the shadows, whether swinging through forest branches, ambushing from well-prepared sites, or lurking in hidden caves, goblins carry a wicked intelligence and a ruthless sense of survival. They lack honor, target the weak, and are quick to flee at the sign of defeat. Cunning, untrustworthy, and notorious even among their kin, goblins live as perpetual schemers, forever caught in a dance of chaos and cruelty.

Hill goblins are the most organized subrace, taking some inspiration from their hobgoblin cousins, though with none of their discipline or physical power. For example, they constantly 'drill' their troops, a process which consists mainly of stronger goblins beating weaker ones until they get tired, and attempt hobgoblin strategies in battle, though goblins tend to become distracted by more immediate threats and opportunities too much for these to be used effectively, not to mention their cowardice far outweighs their respect for authority.

Of all the goblins, hill goblins are the most likely to keep captive other races and animals. Wolves or worgs are a favorite, with most troops' chiefs keeping one or two, or even a whole pack, both to ward against external threats and to keep underlings in line. Their favored form of entertainment is pitting their captives against one another, and against more bloodthirsty (or unlucky) members of the troop, in fighting pits. Although watching prisoners get torn apart by wolves is amusing enough for most, there is a constant hunger for novelty in their entertainment; some troops become very well traveled in their search for strange and exotic beasts to bring back for the pit fights.

Hill goblins have no real preference to the environment they inhabit. The only requirements are a few caves or other shady, hidden areas scattered around well-trafficked roads. For this reason, a hill goblin troop is quite portable, so they suffer less from being displaced or driven out of an area. The troop will generally take over a cavern complex, or a ruined fort if they're lucky, as a base of operations where they will store their scavenged wealth and prisoners.

Where such features do not already exist, hill goblins will dig out, or crudely construct, a series of interlinking escape tunnels. These tunnels are designed to be a squeeze for a typical goblin and nigh on impossible for larger races to fit into, let alone navigate through the pitch blackness and intentionally confusing layout.

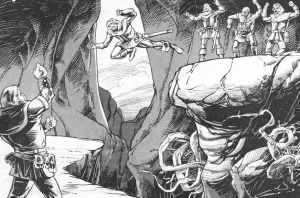

From their central base, scouting parties will range out by night looking for promising and well-traveled ambush sites, spending their days hiding in crevices or undergrowth. Temporary camp will then be established around the site, in a nearby cave if possible, and work will begin on preparing the area. In this, if nothing else, hill goblins are remarkably sophisticated and adaptable, using their environment to the best advantage they can. In hilly areas, rockslides will be rigged, forested areas will have trees ready to fall, garrotes strung between trunks, and spiked rams prepared to swing into the path. In almost every instance, the track will be undermined and ready to collapse into spiked pits, and hunting blinds will be erected, allowing the goblins to attack their victims at a disadvantage, at range, and while hidden.

Hill goblins enjoy the feeling of power, even if they don't always know what to do with it. They have no real sense of personal loyalty, and will do anything it takes to get a taste of power, provided they have a reasonable chance of getting away with it without consequences. They are easily manipulated if they feel as though they have the upper hand, and will often pause to lord it over anything beneath them, giving an enemy time to formulate a plan.

Subservient goblins are boot-lickers of the highest order, hoping to worm their way close to their superiors for rewards of power, and to become trusted enough to stab them in the back should the opportunity arise.

Hill goblins enjoy combat more than other kinds of goblin, part of the inspiration taken from their hobgoblin cousins, and don't mind wading into melee so long as the numbers are on their side. They work together to a reasonable degree out of a desire to retain numerical supremacy rather than a concern for the wellbeing of their fellow goblin. Higher-status goblins work hard to keep face in front of their underlings, and use combat as a way to demonstrate their superiority and as proof for later threats ("See what I did to that elf? That's what I'll do to you if you don't fetch me some supper.")

Goblins' enjoyment of the suffering of others can get them through a battle they would otherwise flee from, but can also work against them; it is common for a goblin to make such a display of gloating over a fallen enemy that they are blind to events unfolding around them (or even taking long enough for the enemy to recover their senses). It does not take much for hill goblins to flee; a few fallen high-ranking goblins, or severe injuries to half their number or so, is usually enough to convince them a battle is not worth fighting until they can muster more troops.

Cave goblins are the most derived subrace. Living their entire lives in the pitch-blackness underground for generations has warped this strain considerably. Their skin is devoid of pigment, almost translucent, with a sparse covering of thin hair. Often, their sensitive skin is raw and blistered where they have encountered strong light, or marred with tumorous sores from simple lack of genetic diversity. In most cases, the eyes have shrunken to a near-vestigial state from lack of use, but in a few lines, they have magnified to enormous proportions to catch whatever light they can.

Cave goblin body types vary dramatically as well. There is debate as to whether goblins of particular physiology undertake certain roles in the troop that they are suited for or whether, like some insect colonies, their bodies develop to fulfill different tasks. Either way, it is difficult to describe a 'typical' cave goblin, as even two individuals of the same caste or designation will look very different.

It is rare to see cave goblins dressed in any more than a few rags but-given the rarity of supplies-they can make a little material go a long way, utilizing every scrap of leather, cloth, or twine they can lay their hands on.

Rather than the typical goblin hierarchy, cave goblins are made up of hundreds, or even thousands, of equally subservient members serving a single "king". This king grows fat on the tribute of his subjects, most of whom are his descendants, being the only reproductive male, and commands an almost religious veneration, with first pick of the food and goods gathered by the troop. In many cases, the king is not a purebred cave goblin, with many kings having a dash or more of hobgoblin, orc, ogre, or even troll at some point in their lineage. Cave goblins flock to strength, so it is not uncommon to see an entirely different subterranean species with a troop of deferential cave goblins in tow.

In the event of the king's death, what little structure the troop had dies with him. In some cases, the largest remaining goblin will, quite literally, expand to fill the role, but it is just as common for the troop to simply collapse and dissolve. If they are lucky, some goblins will find an existing troop to join and a new king to serve. Given the vast size of the caves below, many simply wander, little more than feral beasts.

While other goblins shape their environment to a certain extent, cave goblins are shaped by it. They barely build any structures of their own more complicated than a rickety bridge over a chasm, but instead refine and expand natural caverns, spreading out into honeycombed warrens spanning miles underground. Cave goblins will attempt to eat any potential food item; pickings are slim enough below that they can't afford to be choosy. Most troops are able to eke out a living mostly on subterranean fungus species and cave molds, but any meat they can catch will be enthusiastically devoured before the thought of cooking it can occur.

An individual cave goblin has little personality, and is quite animalistic in its tendencies. As a group, however, they have an unnerving synchronicity, as if they share a common intelligence. This effect increases the more goblins there are in an area, so even huge troops of cave goblins can decide on a course of action as a whole. Whether this is due to some psychic connection, pheromones, or some other strange method of communication is unknown.

Cave goblin kings, on the other hand, tend to be grandiose, viewing themselves as supreme rulers of their own empire and, with hundreds or thousands of thoughtlessly loyal servants at their command, there is an argument to be made that they are right. Those who stroke their egos may only find themselves insulted and patronized before being banished from the kingdom rather than being executed and possibly eaten.

Fighting cave goblins is less like fighting an army and more like fighting the tide; they do not fight as individuals, but as one enormous body. They pay little heed to self-preservation but, like a colony of insects, fight in the manner which best serves the troop as a whole and the safety of the king in particular. Larger cave goblins in particular are bred to fight, and serve no purpose other than to defend the troop with their lives. Their numbers are usually so vast that losses from any one skirmish are incidental, so they can afford to simply throw bodies at the problem until it goes away.

Morale is usually not a problem, but cave goblins will retreat if significant losses would make them less able to defend a more strategically important location. Unlike other goblins, a cave goblin retreat is relatively organized, with smaller goblins simultaneously breaking away from combat while larger goblins cover their escape. If they are retreating to deal with another threat, the opposite is true; the larger goblins move to deal with the new problem, and the smaller goblins attempt to bog down any pursuers with weight of numbers.