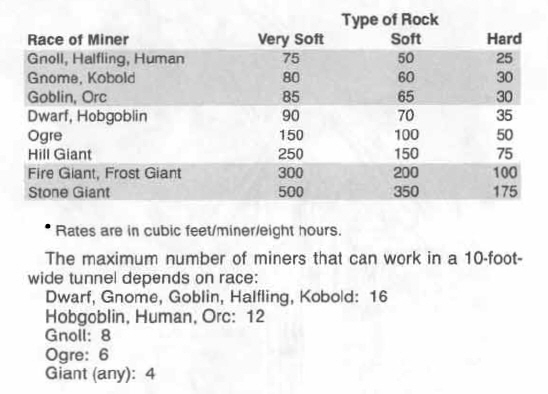

Determine a mine's output by calculating the amount of ore its workers can dig each day, using the table at the end of article: Mining Rates. Some magic, including dig and move earth spells and spades of colossal excavation, may speed the work.

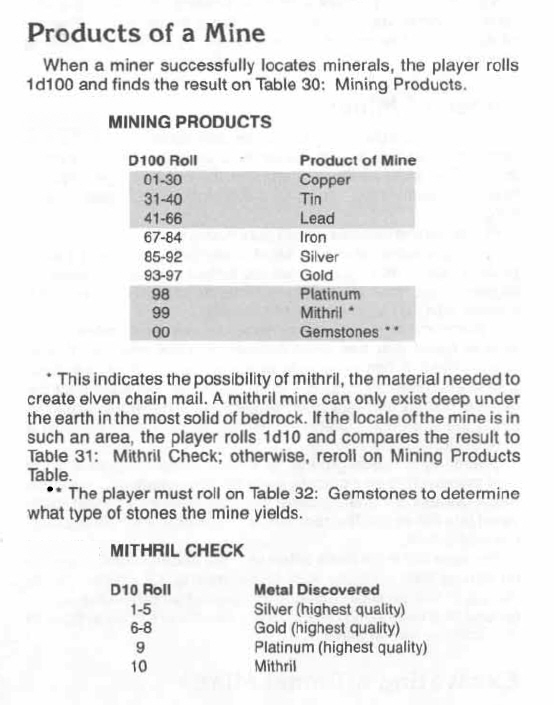

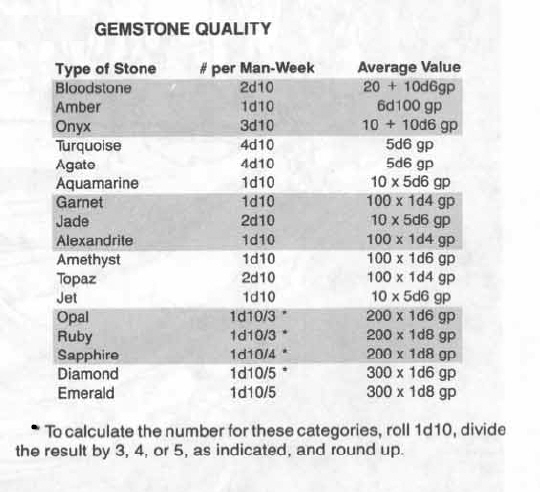

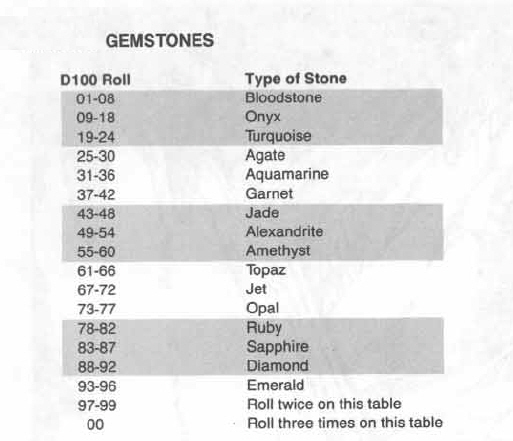

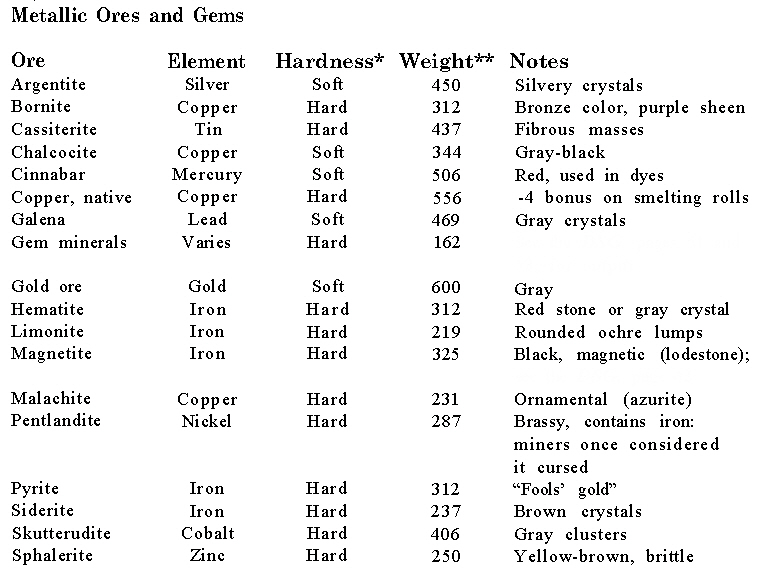

The tables in this article's ending show how difficult ore is to dig, what it weighs, and how much metal can be extracted from it. Tables below can help determine other details, such as the location of veins and their composition. Remember that ore not only needs to be dug, but it must also be transported to a smelter, which we will talk about here in a few moments.

Ore appears in vertical columns called vena profunda, horizontal veins called vena dilatata, or lone masses called vena cumulata. Vena cumulata and vena profunda can be approached from above and are easy to excavate using vertical shafts. Miners dig vena dilatata while lying down; this keeps miners from wasting time digging useless stone but forces them to work in cramped positions, Dwarves excel at this job because they fit into these narrow tunnels. Larger miners can only mine these passages at 75% their normal rate, or one-half the normal rate if they insist on digging tunnels which they can't stand upright.

When characters smelt their ore, you will need to know how much metal the ore contains. Note: in real life, no one mined platinum until the 18th century. It was first found in riverbeds as part of a native alloy. This metal had to be dissolved in aqua regia and reprecipitated to form platinum. The exact methods used remain trade secrets for many, many years.

Once the ore is aboveground, it is sent though a new series of machines. Workers sort ore from stones by hand because plain earth soaks up metal when the two are placed in a furnace together. Each metal requires different treatment. Antimony (silvery-white metalloid) had to be treated gingerly, because alchemists warned that it might turn into lead. Pliny the Elder, a Roman naturalist, recommended mixing silver and gold ores, claiming that the electrum produced would create magical lightning and detect poison by turning black. When gold or silver mingles with lesser ores, acid is used to dissolve the unwanted metal. Adept miners could then reconstitute the other metals from solution. Some miners were even brave enough to dissolve the gold with a mix of hydrochloric and nitric acids, then precipitate it (check a basic chemistry text for details).

Gold can usually be washed out of its ore without heat or acid. There were an amazing variety of machines for purifying it, all based on the principle that gold is heavier than dirt and settles to the bottom when suspended in water. "Panning" by hand is the most basic version of this method. Other systems involved placing the ore on a screen with a tray underneath and running water over it, or lining streambeds with collector plates. Workmen patrolled these chutes with hoes to push lumps of gold back into the plates if they were washing away.

Ore that is to be smelted in a furnace must first be crushed. Some mine owners employed men with hammers to beat the stones, but mines with nearby streams used water wheels to power huge automatic hammers or grindstones to grind soft ore like wheat. (Orcs or other foul creatures might enjoy pounding people in this machinery.) Smelters roasted ore in open fires to burn away sulfur and bitumen before placing it in the furnace. In the smelter, ore was mixed with appropriate fluxes to make metals melt easily and at regular temperatures. Copper will not melt until all traces of iron with it have melted, so it is never worked with iron tools. Most furnaces required large bellows or mechanical blowers, and some were so large that operators needed cranes to open them. However, even these furnaces were not always large enough. A few miners preferred to build hills of ore against windy mountainsides and smelt hundreds of tons at once. Other smelters completely automated the process of refining metal, using water-powered conveyor belts and engines to crush, rinse, strain, and heat the ore.

It is always worthwhile to recycle processed ore. Some smelters accepted their slag instead of a fee, knowing that the slag still contained valuable metal. In the case of gold, even the water that washed it remained precious. Many miners strained gold dust from waste water with sheep's wool, and Agricola suggested that this was the origin of the Greek myth concerning the Golden Fleece. Clever miners could always extract even more gold by mixing mercury with the ore. Smelters put the most promising pieces of stone in a cloth bag with mercury and squeezed the bag until the quicksilver trickled out. The material left inside appeared to be pure gold; it was actually an amalgam, but not even experts could tell.

An alchemist could also use quicksilver to separate gold from silver. The process involved heating a gilt object in mercury, then rapping it sharply. All gold would crumble off, leaving the surface below intact. Other chemists used a powder of sal ammoniac and sulfur that could be applied to an object with oil. Gold would then flake away as soon as the object was heated. These methods were usually used by craftsmen who wanted to remake fine gilt items, but they have obvious applications for theft. A dose of this solution costs 50 gp and can remove 10 lbs. of gold.

Eventually, miners will have dug all the metal they can safely take from a mine. During Roman times, people hoped that ore would grow back in an exhausted mine, as if the earth were a living thing healing its wounds. This might be true on the elemental plane of Earth in a fantasy world. However, even Agricola knew that this was wrong, and he warned that no one should abandon a mine without leaving a record of why it was unsuitable. Many miners wasted fortunes trying to reopen empty mines. Mines in fantasy could be abandoned because of gases or monsters, or because the shafts had nearly tapped underground lakes or magma. But many an adventure might unfold as unknowing characters make their way through old shafts and tunnelings, in search of dangerous beasts or lost and forgotten riches beneath the ground.