The Book That Tamed the Basic D&D Wilderness

Picture this: It's 1985, and you're hunched over your dining room table at 11 PM, frantically flipping through a stack of Basic D&D modules while your players wait. The party just stumbled into a mysterious forest, and you want to throw something exotic at them -- not another orc or goblin, but that weird plant creature you remember from "The Isle of Dread." Was it in the Expert Set? Maybe buried in module X4? Your players are getting restless, making jokes about ordering pizza, and you're sweating bullets trying to find one stupid stat block.

This was the reality for Basic D&D Dungeon Masters across America in the mid-80s. The BECMI line had exploded beyond Frank Mentzer's expectations, spawning dozens of modules, boxed sets, and supplements. Each one introduced new creatures, new horrors, new wonders to populate fantasy worlds. But they were scattered like breadcrumbs across an ever-expanding library of Basic D&D materials. The system's success had created its own monster -- an organizational nightmare that was slowly driving DMs to distraction.

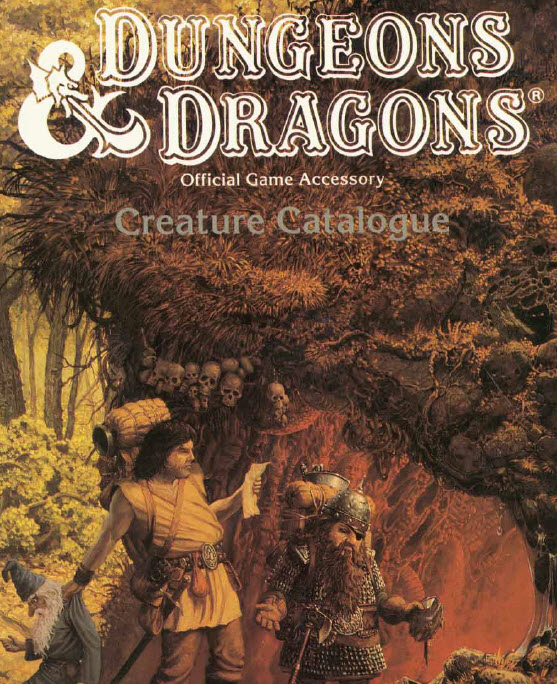

Then, in 1986, three designers from TSR UK stepped forward with a solution that would become legendary among Basic D&D players. Graeme Morris, Phil Gallagher, and Jim Bambra weren't household names like Gygax or Moldvay, but they were about to solve one of gaming's most persistent problems with a slim, 96-page book called the "AC9 Creature Catalogue."

The Great Creature Hunt

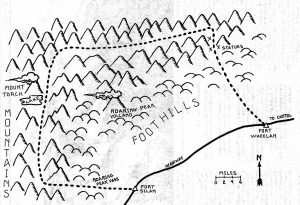

The project began as a massive filing operation. Morris, Gallagher, and Bambra faced a daunting task: track down every single creature that had appeared in the Basic D&D universe up to that point. Not just the famous ones from the basic rules, but the obscure beasts lurking in forgotten corners of tournament modules, the one-off creatures from adventure scenarios, and the regional variants that had been mentioned in passing and never fully detailed.

They combed through years of Basic D&D publications like literary detectives, following paper trails and cross-referencing sources with nothing more than filing cabinets, typewriters, and methodical note-taking. A creature mentioned in "The Isle of Dread" might have appeared earlier in a different form in module B4. A monster from a British tournament might have been adapted for American audiences in a later scenario. Each discovery meant more research, more digging through TSR's archives, more careful documentation.

The process revealed just how organically Basic D&D had grown. What started as a streamlined alternative to Advanced D&D had become a sprawling mythology contributed to by dozens of designers, artists, and writers across two continents. Creatures had evolved, been reimagined, and sometimes contradicted themselves across different publications. The team found themselves not just compiling, but also reconciling -- deciding which version of a creature was definitive when multiple variants existed.

The Anatomy of a Monster

What emerged from this exhaustive process was more than just a reference book. The Creature Catalogue established a new standard for how Basic D&D creatures should be presented. Each entry followed a meticulous format that balanced game mechanics with storytelling potential. Armor Class, Hit Dice, Movement rates -- all the numbers a DM needed for combat. But also crucial details like habitat, behavior, and ecology that helped creatures feel like living parts of a fantasy world rather than random encounter tables.

The book's real genius lay in its organization. Creatures were sorted into six intuitive categories that reflected how they actually functioned in gameplay. Animals covered everything from mundane horses to prehistoric dinosaurs. Conjurations included otherworldly beings and magical constructs. Humanoids encompassed the intelligent races that could serve as allies or enemies. Lowlife covered the creeping, crawling things that inhabited dungeon corners. Monsters were the classic fantasy beasts that had no real-world equivalent. And Undead represented the dark magic that animated the dead.

This wasn't just alphabetical filing -- it was a new way of thinking about fantasy ecology within the Basic D&D framework. A DM planning a forest adventure could flip to the Animals section and immediately see options ranging from ordinary deer to giant spiders to extinct cave bears. Each category offered different narrative possibilities, different levels of challenge, different ways to surprise players who thought they knew every creature in the Basic D&D universe.

The Art of the Isles

The Creature Catalogue also showcased the distinctive style of TSR UK's artistic vision. The book featured work from British artists who brought a different sensibility to fantasy gaming art. Jeff Anderson's detailed pen-and-ink illustrations captured creatures in dynamic poses, showing them in their natural habitats rather than static museum displays. Tim Sell brought a sense of otherworldly menace to his supernatural creatures. Brian Williams added touches of personality that made even the most fearsome beasts feel like characters rather than obstacles.

These artists understood something crucial: players would remember the visual impact of a creature long after they'd forgotten its Armor Class. A well-drawn monster could inspire entire adventure plots, suggest environmental details, or hint at the creature's behavior patterns. The art wasn't just decoration -- it was game design disguised as illustration, perfectly suited to Basic D&D's emphasis on imagination over complex rules.

The Ripple Effect

The impact of the Creature Catalogue extended far beyond its immediate usefulness to Basic D&D players. It established templates that would influence monster design for years to come. The careful balance between game statistics and narrative description became a model for RPG bestiaries. The organizational system influenced how later products would categorize creatures, and the comprehensive approach inspired similar compilations in other game lines.

More importantly, it changed how Basic D&D Dungeon Masters thought about their craft. Instead of frantically searching through scattered modules, they could browse a single book and discover creatures they'd never heard of. The Catalogue encouraged experimentation -- why use another goblin when you could introduce players to a phase tiger or a decapus? It elevated the art of encounter design from random selection to thoughtful curation.

The book also served as a bridge between Basic D&D's scattered early supplements and its more systematized future. Many creatures that had existed only in individual modules found their way into later official products and eventually into the Rules Cyclopedia. The Creature Catalogue essentially canonized an entire bestiary of monsters that might otherwise have been forgotten as their source modules went out of print.

A Different Kind of Monster Manual

What made AC9 special wasn't just its comprehensiveness, but its focus. Unlike Advanced D&D's Monster Manual series, which aimed for encyclopedic coverage, the Creature Catalogue was curated specifically for Basic D&D's sensibilities. It featured creatures that fit the system's emphasis on exploration, discovery, and straightforward adventure. These weren't the cosmic horrors or planar beings that populated Advanced D&D -- they were the weird, wonderful, and dangerous inhabitants of a more grounded fantasy world.

The book included creatures that had become beloved parts of Basic D&D lore: the mysterious shadow elves, the terrifying bone golem, the bizarre caterwaul. Many of these monsters offered unique challenges that couldn't be solved with just sword and spell, encouraging the creative problem-solving that Basic D&D emphasized.

Legacy of the Catalogue

Nearly four decades later, the influence of the Creature Catalogue can still be felt in modern gaming. Many of its creatures have found their way into later editions of D&D, appearing in video games, novels, and new rule sets. The organizational principles it established continue to guide how game designers think about monster ecology and presentation.

But perhaps its most lasting contribution was cultural. The Creature Catalogue represented a moment when the Basic D&D community came together to preserve and organize its collective imagination. It showed that the game belonged not just to its original creators, but to the entire community of players, writers, and artists who had contributed to its growth on both sides of the Atlantic.

For DMs who lived through the pre-Catalogue era, the book remains a monument to organized thinking and collaborative creativity. It turned chaos into order, scattered inspiration into accessible reference, and proved that sometimes the most important innovations are the ones that simply make existing greatness easier to find.

The next time you're running a Basic D&D game and need the perfect creature to surprise your players, remember those DMs from 1985, frantically shuffling through module boxes at midnight. The Creature Catalogue made sure their problem would never be your problem -- and that's perhaps the most quietly heroic thing a game supplement has ever accomplished.