The word "castle" conjures up images of soaring stone walls looming high upon craggy pinnacles of rock, surveying the land below with an imposing presence. When we think of castles, we think of King Arthur and his knights riding forth from a magnificent castle of gold, with colorful pennants flapping smartly atop the crenelated towers, while fair maidens wave from high windows. We see a brooding, mist-covered stone gargantua vigilantly guarding a loch in the Highlands of Scotland. We recall the many-spired, gravity-defying home of Cinderella at Disneyland, modeled after an actual Bavarian wonder of architecture.

Throughout history, the most lasting evidence handed down to us from the peoples of those times has been the fortified homes they built to withstand the attacks of their enemies. From the ancient peoples of the Fertile Crescent, who built the first walls around the first villages, to the Romans, whose legions brought engineering genius with them when they conquered the Gauls and Celts, to the Europeans of the Middle Ages, who constructed over the span of decades massive stone homes to protect their lands and their people from one another - modern historians have learned much about our past from these architectural marvels.

Yet, when the typical Dungeon Master sits down to create an impregnable fortress, the result too often falls woefully short. Too many times, a wonderful adventure is planned around a frontier stronghold only to have that stronghold never develop beyond a few simple lines quickly scratched out on a piece of graph paper, with no real feeling or flavor. More than one new project has crossed my editing desk here at TSR with a castle or walled fortress included that fails to inspire any sense of grandeur. With all the source material that is out there to draw upon, this does not have to be the case.

To understand how to create more realistic fortifications in a game setting, we need to learn more about how they developed historically. The first part of doing that is understanding the technological evolution of castles. The massive stone constructions that we think of as castles did not simply sprout one day from a feudal king's imagination. The earliest medieval constructions were nothing more than a palisade wall of cut timbers sur-rounding it and a ditch surrounding that built on a hill. There were various forms of this construction type, known as a motte-and-bailey construction, but it was essentially the earliest recognizable form of castle. As the years passed, knowledge of the strengths and weaknesses of this type of fortification were taken into account with newer and better forms of defense. The wooden palisade wall was replaced by stone walls; the curtain wall was developed; siege engines were constructed; square towers were eventually abandoned in favor of round ones; and so on.

The second fundamental concept behind castle development is financial in nature. Because construction was such an expensive undertaking, it was rarely done all at once. A feudal lord might gather higher-than-usual taxes for a number of years, and still be able only to construct a small motte-and-bailey style home. Perhaps his son, the next lord, would accumulate enough wealth to add to the palisade wall, or maybe even to replace the wooden building at the top of the hill with a stone one, but he certainly never considered starting from scratch with a new site and a new plan. Adding onto the original defenses was typically the only option. As a result, most castles grew in a sort of "building block" fashion, one or two sections at a time, rather than with a complete architectural plan drawn up for the final product.

Now that we have a better grasp on how castles developed over time, let's look at another consideration in castle design, namely, using natural features prominently in the layout of the fortifications. The first of these is making certain that the castle has exclusive access to a water supply. Usually this is a well, but some-times the castle was built around a natural spring. If neither of these was available, special pools were built on roofs and in courtyards to catch rainwater and store it. This was not as reliable as a well or spring, but it was better than letting the enemy dam or poison a stream.

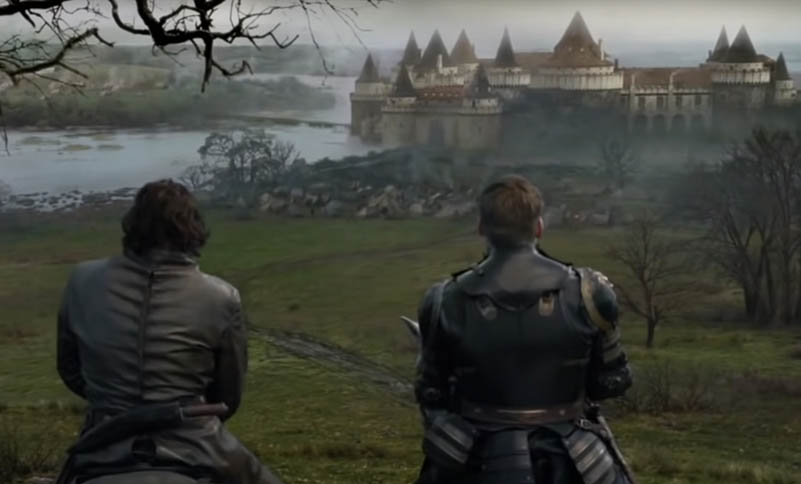

The second way natural features were used was, of course, as natural defenses. Why build an artificial hill when a natural one would do just fine? Why dig a huge ditch to slow up attackers and discourage heavy siege engines when a natural barrier, such as a river, is already there? In any book on castles worth its salt, you should be able to find plenty of photographs that show castles all over Europe and England sitting on a high outcropping of rock, butting up against some water source, or both.

There are two benefits from putting a castle on high ground and behind natural barriers. The first is to get a great view of the surrounding countryside. The farther away the enemy is when spotted, the better. The second advantage is making it as difficult as possible for that enemy to reach those massive stone walls. Having to scramble up a steep hill with bad footing or swim or boat across a stream or lake makes a besieging army very vulnerable to attacks from the castle.

All this is common sense, right? Using natural obstacles rather than building your own also seems like a no-brainer, correct? Consider the last time you actually saw a natural rock outcropping that was perfectly symmetrical in shape, surrounded on four sides with a perfectly symmetrical river, and ready for a castle with four walls and a tower at each corner.

Now we've broadened our understanding of just what a castle is and isn't. Where do we go from here? We go to the world of fantasy, of course. We're ready to sit down and design that impregnable fortress that we just know the PCs can't infiltrate, or that their lord lives in, or whatever. We already have a problem, though.

In a game setting that sports powerful magic and mythical creatures, some of the tenets of castle construction no longer apply. A wizard with a transmute rock to mud spell can do some pretty ugly things to a castle. Even the teleport spell or the psionic ability Dimensional Door can get around castle defenses. Attacks from a flying creature, such as a dragon, make walls practically obsolete. These kinds of problems call for similar solutions. Still, for the average petty lord, or in a low-magic campaign, we can begin planning our castle.

As we discuss how to design our own castles, let's use each step in an ongoing example. By the time we're finished, we will have a complete castle that we can plop down in practically any medieval campaign world. We can then take these steps and, with only slight tinkering, develop any castle, city, etc., for any occasion that we need, and come up with some- thing that is both unique and realistic.

The first thing we want to do is select a site. We want a place that has hills, trees, stone outcroppings, lakes, streams-the whole gamut of geographical features. One way to do this is to make them up. This is fine, and can even be pretty cool, if you know how to do it. Picture a place and draw in some features. Just make sure that you don't have rivers running over a high hill rather than around it, and that the place isn't filled with more geological wonders than we find in all of North America. This method is good if you al-ready have some preconceived ideas about the location of the proposed castle.

Once you have one of those, picking a likely place for a castle can be pretty easy. Just make sure you get a map that has the type of terrain that you need. Either way, I suggest you stay away from graph paper, at least initially. All that grid is going to do is lock your mind into the idea of rigidity and symmetry. Use unlined paper instead, to allow yourself the freedom to adapt to the terrain rather than the grid.

Once I had my topographical map, I thought about why this was, strategically speaking, a good place for a castle. I decided that the lake sat at the foot of a valley walled in on the other sides by fairly steep mountains. There is only one way around the lake, and that is via the road that passes on this side of it's the mountains come right down to the shore everywhere else. So, this point of mountain looks down on the only reasonable way into the valley and is therefore a great place to build our castle.

Once you have a topographical area set up, it's time to think about how a castle might start there. It's a good idea to have several photocopies of your area ready. This way, you can design the castle in several stages, allowing for the passage of time and showing how the castle has been modified over the years. It also will allow you to work on a trial-and-error basis without destroying your only copy of the map. Start off with something simple, like one of the motte-and-bailey plans.

For the second phase of development, think about how the castle could be expanded, both to gain more room and to take advantage of newer construction techniques. To minimize time, effort, and expense, try to incorporate as much of the existing structure as possible instead of tearing it down. Remember to utilize the natural terrain to best advantage.

From this point, continue adding new phases, pretending that changes and additions have been made to the construction over the years, taking into account new technology and resources. If you are operating within a high-fantasy setting, you might include some anti-dragon features or some traps for infiltrators using magic to get in. Throw in whatever you can think of to adapt the construction to the setting. You can do as few or as many phases as you think is appropriate for the setting.

Now that we see that a typical castle is anything but typical, let's discuss just what might be found inside its walls. Recalling some of those castles that I have seen poorly designed (and yes, I have designed a few myself), one thing that sticks out is the amazing lack of creativity that went into the interior rooms. Usually, that four-walled square castle had a roof that spanned the entire thing, and underneath it were five or six huge rooms connected by doors from a central chamber. Along with this went one of the biggest castle killers of them all, the wall without width. Designers do it all the time, in most of the maps we draw. Dungeon rooms sit side by side on a piece of graph paper with a pencil-thin line dividing them. How thick is the wall? "It doesn't really matter," we say. Wrong. Walls designed to hold up several storeys of stone tower or to withstand the pounding of heavy siege equipment were built 10, 20, or 30 feet thick. Don't over-look the spatial requirements of huge load-bearing and defensive walls when you draw up plans for your fortress.

So what goes into the spaces between those massive walls? More than you might think. Of course, there is a central hall. Every self-respecting lord had one, with a big feasting table and walls high enough to display all his spoils of war. In a tower-type construction, the main hall was usually two or even three stories high, with a balcony running around its perimeter on the upper floors. That way, even people who were upstairs could see what was going on down in that main hall.

There are quite a few features to pay attention to in this plan. First, notice that the walls are thick (typically 5' for the interior walls and 10' for the outer ones). There's room within the walls for a fireplace in the kitchen, as well as the secret spiral stairwell off the Parley Room. Second, notice that the plan is far from symmetrical, and that there are a variety of different areas included. While far from complete, this plan does manage to include several distinct areas to make the castle much more interesting. There are several more upper floors, as well as a basement. (That spiral stairway going down from the kitchen leads to a wine cellar, for example.) The rest of the castle can be designed in the same way, incorporating any unusual features that seem interesting.

When you get the palace developed and detailed the way you want it, you can make a larger, more permanent map that can be used as a base for all your future plans, sieges, expansions, etc. You will need a map of each level, the roofs, and the basements. You can use different colors to key your map like we did.

You can apply these principles to other kinds of fortifications, too. Just take a look at a map of any of the ancient cities, like Rome or Istanbul. You will see that walls were expanded, and centers of power altered and improved as the population increased. The secret is knowing that no fortification was ever built without regard for topographical features, and that no castle was built all at once.