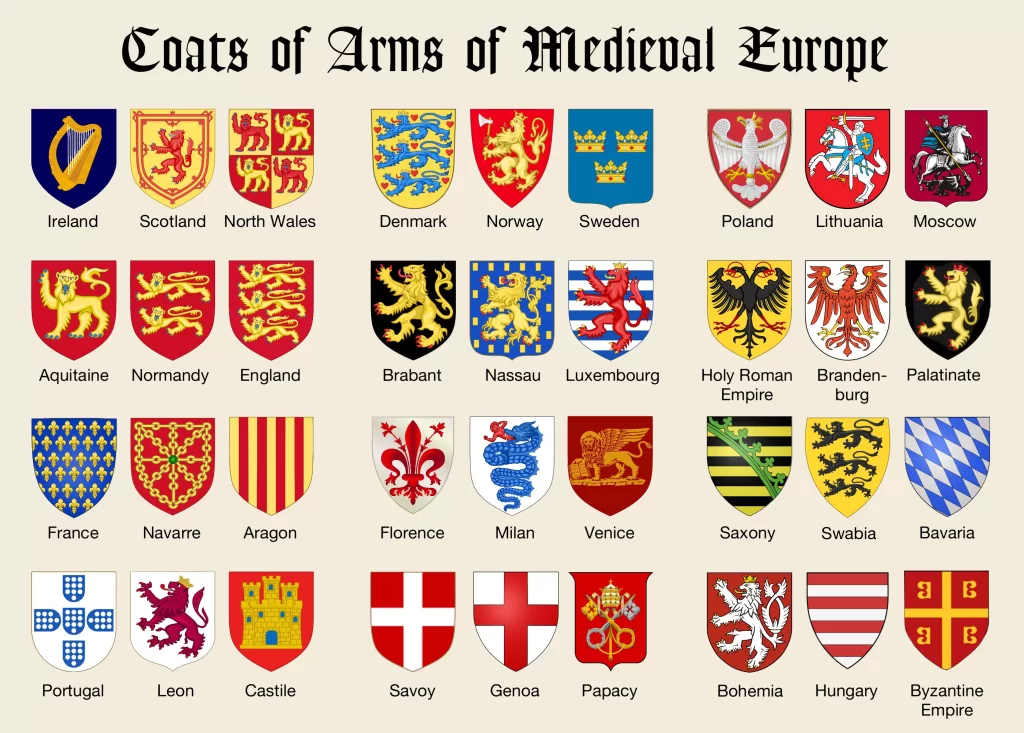

The term "heraldry" is widely used to denote the study and use of coats of arms to identify persons, families, or organizations. The correct term for this is "armory," while "heraldry" properly refers to all the duties of heralds. These duties included record keeping (especially of coats of arms), acting as messengers and negotiators, and organizing events such as tournaments, coronations, and celebrations. This article is concerned only with armory and its application to fantasy role-playing.

The origins of the use of coats of arms are obscure. In ancient Israel and Rajput India, badges were used to identify tribes or people loyal to a prince. The seal cylinders used in ancient Mesopotamia to identify persons, American Indian totems, and some flags are also distant relatives of armory.

The purpose of the coat of arms was to identify at a distance the man carrying or wearing the colors. During the Norman conquest of England and the First Crusade (both in the eleventh century) coats of arms did not exist, though a few individuals might bear an animal figure on a shield. But as helms improved they covered more of a man's face, and armor also obscured the wearer's identity as it became more complex and covered more of the wearer's body. Moreover, the Crusaders, speaking a dozen different languages and unfamiliar with their new comrades, needed some simple means of recognizing one another. It was not enough to know a man's nationality; troops were loyal to individuals, not to nations.

Gradually, leaders began to adopt simple colored patterns to display on shields, surcoats, and flags to extricate themselves and their followers from the anonymity of full armor. Words or letters would not have served, of course, in a world of nearly universal illiteracy. A large display was necessary in a military system dominated by armored cavalry, for it was vital to know whether a man was friend or foe before one charged.

Arms also served as patterns on seals and signet rings. In some cases, such as the Great Seal of England, any document not stamped with the proper seal had no validity or force in law.

At first the patterns adopted were simple, with ease of recognition uppermost in mind. But as more knights adopted arms, more elaborate patterns were needed to avoid duplication. Nevertheless, duplication could occur, on at least one occasion requiring the personal intervention of the King of England to determine who rightfully bore the arms.

It became evident that some record of who was entitled to which arms would help keep the peace. At this same time (fourteenth century), sovereigns began to grant arms to those deemed worthy, and finally it became illegal to adopt a coat of arms without consent of the sovereign. Military leaders usually adopted or obtained coats of arms, and so the holders of arms were usually nobility.

In parts of Europe, only those who could prove that all 16 of their great great-grandparents were entitled to bear arms ("seize quartiers") could themselves bear arms. But in other areas, even certain peasants possessed coats of arms. Clergy also became associated with arms. The abbot of a monastery or bishop of a province carried the arms of the body he represented. And though clergy were not supposed to fight, many did so and consequently deserved arms to identify themselves and their retainers. Military orders (such as the Knights Templars) and guilds also obtained arms.

Before some of the rules and conventions of armory are described, it should be pointed out how armory may be incorporated into role-playing. First, the DM must decide where a country lies in the progression from assumed arms to granted arms. If the country is lawful or neutral, loyal and obedient to a single sovereign lord, then the lord may well have begun to grant arms while prohibiting the assumption of arms without his permission.

In a less orderly country, or an area ruled by a lord who owes nominal allegiance to a higher sovereign, powerful individuals may assume arms without fear of prosecution from the ruler, though they still must beware of a dispute with someone who already has similar arms. Such a dispute might be settled by battle or in a High Court.

Coats of arms may be held by any powerful individual, though fighters are most likely to have arms, and a man with many retainers, even a merchant or other non-adventurer, is more likely to require arms than is a lone magic-user or thief. Possession of arms is considered to be a prerogative of a gentleman, so a thief or other person living on the fringes of acceptable society is not likely to bear arms.

In chaotic areas, duplication of arms might be common, even deliberate. Many leaders might not bear arms at all, preferring some other method of identification such as a distinctive style of armor or helmet.

In any area where infantry rather than cavalry dominates the armed forces, coats of arms could be less commonly used. Of course, flags can incorporate coats of arms, but they can also represent nations rather than individual lords. Where only the arms are used for identification, it is possible to impersonate an individual or pretend to be a group of retainers of some lord. There are many opportunities to make armory and heraldry a part of the game if the DM is willing to do the necessary groundwork.

An "achievement of arms" or "armorial bearings" consists of several elements-the crest, helm, supporters, mantling, and shield. But for the original purpose (identification) only a patterned shield was used, and this is the only element this article will describe.

Armory uses a special language, descended from French and Old English, to describe the pattern of arms. While the details can become complex, the objective was to describe the pattern briefly, elegantly, and uniquely, however strange the words may sound today. As the elements of the patterns are discussed, some of the words needed to blazon, or describe, the arms will be introduced.

Only nine contrasting tinctures are used on a shield, divided into five colors, two metals, and two furs. For practical use, the metals can be considered two additional colors, while the furs are patterns of two other tinctures. The colors are black (sable), red (gules), blue (azure), green (vert), and purple (purpure). In England, orange-brown (tenne) and sanguine (murry) are occasionally used, but they are regarded as tainted colors indicating illegitimacy or other fault or flaw in the bearer's ancestry.

The metals are gold (or), usually represented as yellow, and silver (argent), usually shown as white.

The rarely used furs are ermine and vair. Ermine is an argent background covered by regularly spaced black marks, which consist of an arrowhead surmounted by three small dots, one just above the point and one to either side and slightly lower. This "fur" derives from the fur of the arctic stoat (ermine), which, used as the lining of cloaks, became a symbol of rank and office. Vair (from an unusual squirrel fur) is represented by rows of bell shapes, the argent upside down and the other tincture (usually azure) right side up so that the two rows fit together alternately; four sets cover the shield.

The first element of the blazon (description) is the tincture of the shield as a whole, the field. Occasionally the field may be a pattern of small objects, similar in effect to one of the furs. Next comes the charge, describing the object placed over the field. Sometimes a party field (a field of two tinctures used in roughly equal amounts) is used without a basic charge.

The field and charge alone are enough to construct many distinctive patterns, but most arms include elaborations of the charge. These include heraldic animals, crosses, towers, abstract shapes, common beasts - virtually anything the originator of the arms desires,

Arms may be differenced and marshalled as well, to indicate marriage alliances, sons, bastardy, and the like. Differencing and marshalling can be a complicated subject and should be pursued further only by those readers who are sufficiently interested.

The rule of armory is that no color should be placed on a color and no metal on a metal. For example, a gold charge may be placed on a blue background (or vice versa), but a gold charge should not be placed on a silver background. This rule was adopted to heighten contrast and improve visibility at a distance. It is done, however, and whether the rule should be enforced (and how) must be left to each DM.

The parts of the field are named in the language of armory as follows. The left side or flank as one looks at the shield is the dexter, the right side the sinister. (These latter terms derive from the Latin for right and left, respectively, but this is from the viewpoint of someone behind the shield, the one holding it.)

The chief is the top third of the field; the fess (strip across the middle of a shield) is the middle third; and the base is the bottom third.

When a man assumed arms, he often chose charges symbolic of himself or his family. The less solemn might make a play on words, such as the family of Catt, Catton, or Keats using a cat as a charge. William Shakespeare's arms showed a hand grasping several spears. An animal related to the location or nature of his estates, such as a fish for an island-dwelling knight, might be preferred.

The more serious or idealistic might choose symbols to emphasize their courage or good fortune. Thus the lion, symbol of valor, was a favorite charge, and the dragon likewise. Religious piety could be expressed in the arms. The Christian (Latin) cross is the classic means, but a special cross of Calvary, angels, or other religious symbols might be used.

A list of some types of popular charges includes: divine beings, humans, lions, deer (stag, hind, etc.), felines (cat, panther, Bengal tiger, etc.), bears, elephants, camels, birds, fish, insects, monster (dragons, wyverns, unicorns, griffons, etc.), celestial objects (sun, moon, stars ["etoiles"], clouds), trees, plants, flowers (fleurdelis, rose, etc.), and certain inanimate objects (castle, five-pointed star ["mullet"], caltrop, whirlpool, galley, sword). When a charge is presented in its natural color, the blazon is said to be "proper."

There are a myriad of ways for the DM to incorporate the use of armory in the campaign. Three general suggestions are given below, and should cause other possibilities to come to mind.

First, a player who possesses arms hears of or meets a non-player character with similar arms. Is this an honest mistake, or is the NPC trying to deceive others? The player character can hardly ignore the situation - he'll have to investigate further.

Second, some non-player character accuses a player character of stealing the accuser's armorial bearings. A challenge to combat or an appeal to the high court may result. The accusation may be only a means to some dark end.

Third, in order to accomplish some goal the player desires - for example, marriage to a noble's daughter, he must earn arms from the King. This means he must visit the King (a wilderness adventure in itself) to discover what he can do to earn arms, and then he'll have to accomplish that task.