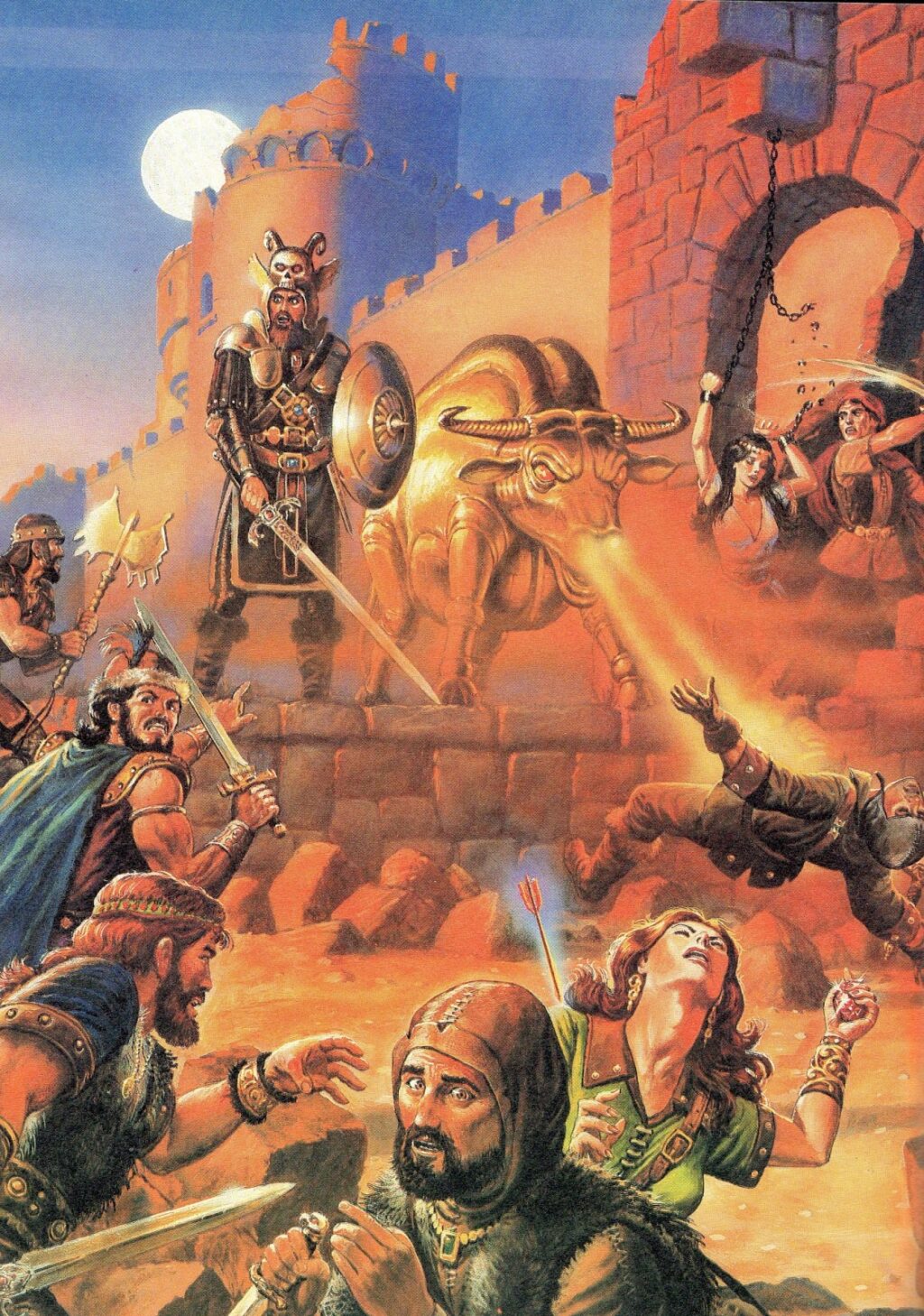

Some of the most powerful weapons player characters have at their disposal in the AD&D game are magical spells. Through spells a player character can control earthquakes, call lightning out of the sky, heal grievous injuries, hurl explosive balls of fire, create barriers of stone, fire, and ice, and learn secrets long forgotten. These are only a few of the things player characters can do once they master the strange lore of spells.

Not every character is capable of casting spells, however. This ability requires a certain amount of aptitude, depending on the type of spells cast. Wizard spells are best mastered by those with keen intelligence and patience for the long years of study that are required. Priest spells call for inner peace and faith and an intense devotion to one's calling.

The vast majority of people in a fantasy campaign lack these traits or have never had the opportunity to develop them. The baker may be a bright and clever fellow, but, following in his father's footsteps, he has spent his life learning the arts of bread making. There has simply been no time in his life for the study of old books and crumbling scrolls. The hard-working peasant may be pious and upright in his faith, but he lacks the time for the contemplative and scholarly training required of a priest. So it is only a fortunate few who have the ability and opportunity to learn the arcane lore of spellcasting.

A few character classes have a limited ability to cast spells. The ranger, through his close association with nature, is able to cast a few spells, though his choices are limited to his natural inclinations. The paladin, through his devotion and humility, can use some of the spells of the priest. The bard, through luck, happenstance, curiosity, and perseverance, can manage a few wizard spells, perhaps by persuading a lonely wizard to reveal his secrets.

Regardless of their source, all spells fall into the general categories of wizard or priest. Although some spells appear in both categories, in general the categories differ in how spells are acquired, stored, and cast.

Wizard Spells

Wizard spells range from spells of simple utility to great and powerful magics. The wizard spell group has no single theme or purpose. The vast majority of wizard spells were created by ancient wizards for many different purposes. Some are to serve the common man in his everyday needs. Others provide adventurers with the might and firepower they need to survive. Some are relatively simple and safe to use (as safe as magic can be); others are complicated, filled with hazards and snares for the rash and unwary. Perhaps the greatest of all wizard spells is the powerful and tricky wish. It represents the epitome of spell-casting--causing things to happen simply because the wizard desires it to be so. But it is a long and difficult task to attain the mastery needed to learn this spell.

Although some characters can use spells, the workings of magic are dimly understood at best. There are many theories about where the power comes from. The most commonly accepted idea is that the mysterious combination of words, gestures, and materials that make up a spell somehow taps an extradimensional source of energy that in turn causes the desired effect. Somehow the components of the spells--those words, gestures and materials--route this energy to a specific and desired result. Fortunately, how this happens is not very important to the majority of wizards. It is enough to know that "when you do this, that happens."

Casting a wizard spell is a very complicated ordeal. The process of learning the correct procedure to cast a spell is difficult and taxing to the mind. Thus, a wizard must check to see if he learns each new spell (according to his Intelligence--see Table 4). Furthermore, there is a limit to just how much of this strangeness--illogical mathematics, alchemical chemistry, structuralist linguistics--a wizard's mind can comprehend, and so he must live with a limit to the number of spells he can know.

As the wizard learns spells, he records their arcane notes into his spell books. Without spell books, a wizard cannot memorize new spells. Within them are all his instructions for memorizing and casting all the spells he knows. As the wizard successfully learns a new spell, he carefully enters its formula into his spell books. A wizard can never have a spell in his books that he does not know, because if he doesn't understand it, he cannot write the formula. Likewise, he cannot enter a spell into his books that is higher in level than he can cast. If he finds an ancient tome with spells of higher power, he must simply wait until he advances to a level at which he can use them.

The exact shape and size of a character's spellbooks is a detail your DM will provide. They may be thick tomes of carefully inked parchment, crackling scrolls in bulky cases, or even weighty clay tablets. They are almost never convenient to carry around. Their exact form depends on the type and setting of the campaign world your DM has created.

Ultimately, it is the memorization that is important. To draw on magical energy, the wizard must shape specific mental patterns in his mind. He uses his spell books to force his mind through mental exercises, preparing it to hold the final, twisted patterns. These patterns are very complicated and alien to normal thought, so they don't register in the mind as normal learning. To shape these patterns, the wizard must spend time memorizing the spell, twisting his thoughts and recasting the energy patterns each time to account for subtle changes--planetary motions, seasons, time of day, and more.

Once a wizard memorizes a spell, it remains in his memory (as potential energy) until he uses the prescribed components to trigger the release of the energy patterns. The mental patterns apparently release the energy while the components shape and guide it. Upon casting, the energy of the spell is spent, wiped clean from the wizard's mind. The mental patterns are lost until the wizard studies and memorizes that spell again.

The number of spells a wizard can memorize is given by his level (see Table 21); he can memorize the same spell more than once, but each memorization counts as one spell toward his daily memorization limit. Part of a wizard's intelligence can be seen in the careful selection of spells he has memorized.

Memorization is not a thing that happens immediately. The wizard must have a clear head gained from a restful night's sleep and then has to spend time studying his spell books. The amount of study time needed is 10 minutes per level of the spell being memorized. Thus, a 9th-level spell (the most powerful) would require 90 minutes of careful study. Clearly, high-level spellcasters do not lightly change their memorized spells.

Spells remain memorized until they are cast or wiped from the character's mind by a spell or magical item. A wizard cannot choose to forget a memorized spell to replace it with another one. He can, however, cast a spell just to cleanse his mind for another spell. (The DM must make sure that the wizard does not get experience for this.)

Schools of Magic

Although all wizard spells are learned and memorized the same way, they fall into nine different schools of magic. A school of magic is a group of related spells.

Abjuration spells are a group of specialized protective spells. Each is used to prevent or banish some magical or nonmagical effect or creature. They are often used to provide safety in times of great danger or when attempting some other particularly dangerous spell.

Alteration spells cause a change in the properties of some already existing thing, creature, or condition. This is accomplished by magical energy channeled through the wizard.

Conjuration/summoning spells bring something to the caster from elsewhere. Conjuration normally produces matter or items from some other place. Summoning enables the caster to compel living creatures and powers to appear in his presence or to channel extraplanar energies through himself.

Enchantment/charm spells cause a change in the quality of an item or the attitude of a person or creature. Enchantments can bestow magical properties on ordinary items, while charms can unduly influence the behavior of beings.

Greater divinations are more powerful than lesser divinations (see below). These spells enable the wizard to learn secrets long forgotten, to predict the future, and to uncover things hidden or cloaked by spells.

Illusions deal with spells to deceive the senses or minds of others. Spells that cause people to see things that are not there, hear noises not made, or remember things that never happened are all illusions.

Invocation/Evocation spells channel magical energy to create specific effects and materials. Invocation normally relies on the intervention of some higher agency (to whom the spell is addressed), while evocation enables the caster to directly shape the energy.

Lesser divination spells are learnable by all wizards, regardless of their affiliation. This school includes the most basic and vital spells of the wizard--those he needs to practice other aspects of his craft. Lesser divinations include read magic and detect magic.

Necromancy is one of the most restrictive of all spell schools. It deals with dead things or the restoration of life, limbs, or vitality to living creatures. Although a small school, its spells tend to be powerful. Given the risks of the adventuring world, necromantic spells are considered quite useful.

Learning Spells

Whether a character chooses to be a mage or a specialist in one of the schools of magic, he must learn his spells from somewhere. While it might be possible for the exceptional wizard to learn the secrets of arcane lore entirely on his own, it isn't very likely. It is far more likely that your character was apprenticed to another wizard as a lad. This kindly (severe), loving (callous), understanding (ill-tempered), generous (mean-spirited), and upright (untrustworthy) master taught your character everything he knows at the start of the game. Then, when it was time, the master sent him into the world (threw him out) with a smile and a pat on the back (snarling with his foot on your character's behind).

Or perhaps your character studied at a proper academy for wizards (if your DM has such things). There he completed his lessons under the eye of a firm (mean) but patient (irritable) tutor who was ready with praise for good work (a cane for the slightest fault). But alas, your character's parents were impoverished and his studies had to end (fed up with this treatment, your youthful character fled during the night).

As you can see, there are a number of ways your character might have learned his spells.

The one good thing that comes from your character's studies is his initial spell book. It may have been a gift from his school or he may have stolen it from his hated master. Whatever the case, your character begins play with a spell book containing up to a few 1st-level spells. Your DM will tell you the exact number of spells and which spells they are. As your character adventures, he will have the opportunity to add more spells to his collection.

When your character attains a new level, he may or may not receive new spells. This is up to your DM. He may allow your character to return to his mentor (provided he departed on good terms!) and add a few spells to his book. It may be possible for your character to copy spells from the spell book of another player character (with his permission, of course). Or he may have to wait until he can find a spell book with new spells. How he gets his spells is one of the things your DM decides.

In al cases, before he can add a new spell to his spell book, you have to check to see if your character learns that spell. The chance of learning a spell depends on your wizard's Intelligence, as given in Table 4. This chance may be raised or lowered if your character is a specialist.

Illusions

Of all spells, those of the illusion school cause the most problems. Not that they are more difficult for your player character to cast, but these spells are more difficult for you to role-play and for your DM to adjudicate. Illusions rely on the idea of believability, which in turn relies on the situation and the state of mind of the victim. Your DM must determine this for NPCs, which is perhaps an easier job. You must role-play this for your character.

Spells of this school fall into two basic groups. Illusions are creations that manipulate light, color, shadow, sound, and sometimes even scent. Higher level illusions tap energy from other planes, and are actually quasi-real, being woven of extradimensional energies by the caster. Common illusions create appearances; they cannot make a creature or object look like nothing (i.e., invisible), but they can conceal objects by making them look like something else.

Phantasms exist only in the minds of their victims; these spells are never even quasi-real. (The exceptions to this are the phantasmal force spells, which are actually illusions rather than phantasms.) Phantasms act upon the mind of the victim to create an intense reaction--fear being most common.

The key to successful illusions or phantasms is believability, which depends on three main factors: what the caster attempts, what the victim expects, and what is happening at the moment the spell is cast. By combining the information from these three areas, the player and the DM should be able to create and adjudicate reasonable illusions and phantasms.

When casting an illusion or phantasm, the caster can attempt to do anything he desires within the physical limits of the spell. Prior knowledge of the illusion created is not necessary but is extremely useful.

Suppose Delsenora decides to cast a phantasmal force spell and can choose between creating the image of a troll (a creature she has seen and battled) or that of a beholder (a creature she has never seen but has heard terrifying descriptions of). She can either use her memory to create a realistic troll or use her imagination to create something that may or may not look like a real beholder. The troll, based on her first-hand knowledge of these creatures, is going to have lots of little details--a big nose, warts, green, scabby skin, and even a shambling troll-like walk. Her illusion of a beholder will be much less precise, just a floating ball with one big eye and eyestalks. She doesn't know its color, size, or behavior.

The type of image chosen by the caster affects the reaction of the victim. If the victim in the above case has seen both a troll and a beholder, which will be more believable? Almost certainly it will be the troll, which looks and acts the way the victim thinks a troll should. He might not even recognize the other creature as a beholder since it doesn't look like any beholder he's ever seen. Even if the victim has never seen a troll or a beholder, the troll will still be more believable; it acts in a realistic manner, while the beholder does not. Thus, spellcasters are well-advised to create images of things they have seen, for the same reason authors are advised to write about things they know.

The next important consideration is to ask if the spell creates something that the victim expects. Which of these two illusions would be more believable--a huge dragon rising up behind a rank of attacking kobolds (puny little creatures) or a few ogres forming a line behind the kobolds? Most adventurers would find it hard to believe that a dragon would be working with kobolds. The dragon is far too powerful to associate with such little shrimps. Ogres, however, could very well work with kobolds--bossing them around and using them as cannon fodder. The key to a good illusion is to create something the victim does not expect but can quickly accept.

The most believable illusion may be that of a solid wall in a dungeon, transforming a passage into a dead end. Unless the victim is familiar with these hallways, he has no reason not to believe that the wall is there.

Of course, in a fantasy world many more things can be believed than in the real world. Flames do not spring out of nowhere in the real world, but this can happen in a fantasy world. The presence of magic in a fantasy world makes victims more willing to accept things our logic tells us cannot happen. A creature appearing out of nowhere could be an illusion or it could be summoned. At the same time, you must remember that a properly role-played character is familiar with the laws of his world. If a wall of flames appears out of nowhere, he will look for the spellcaster. A wall blocking a corridor may cause him to check for secret doors. If the illusion doesn't conform to his idea of how things work, the character should become suspicious. This is something you have to provide for your character and something you must remember when your character attempts to use illusions.

This then leads to the third factor in the believability of an illusion, how appropriate the illusion is for the situation. As mentioned before, the victim is going to have certain expectations about any given encounter. The best illusions reinforce these expectations to your character's advantage. Imagine that your group runs into a war party of orcs in the local forest. What could you do that would reinforce what the orcs might already believe? They see your group, armed and ready for battle. They do not know if you are alone or are the advance guard for a bigger troop. A good illusion could be the glint of metal and spear points coming up behind your party. Subtlety has its uses. The orcs will likely interpret your illusion as reinforcements to your group, enough to discourage them from attacking.

However, the limitations of each spell must be considered when judging appropriateness. A phantasmal force spell creates vision only. It does not provide sound, light, or heat. In the preceding situation, creating a troop of soldiers galloping up behind you would not have been believable. Where is the thunder of hooves, the creak of saddle leather, the shouts of your allies, the clank of drawn metal, or the whinny of horses? Orcs may not be tremendously bright, but they are not fooled that easily. Likewise, a dragon that suddenly appears without a thunderous roar and dragonish stench isn't likely to be accepted as real. A wise spellcaster always considers the limitations of his illusions and finds ways to hide their weaknesses from the enemy.

An illusion spell, therefore, depends on its believability. Believability is determined by the situation and a saving throw. Under normal circumstances, those observing the illusion are allowed a saving throw vs. spell if they actively disbelieve the illusion. For player characters, disbelieving is an action in itself and takes a round. For NPCs and monsters, a normal saving throw is made if the DM deems it appropriate. The DM can give bonuses or penalties to this saving throw as he thinks appropriate. If the caster has cleverly prepared a realistic illusion, this certainly results in penalties on the victim's saving throw. If the victim were to rely more on scent than sight, on the other hand, it could gain bonuses to its saving throw. If the saving throw is passed, the victim sees the illusion for what it is. If the saving throw is failed, the victim believes the illusion. A good indication of when player characters should receive a positive modifier to their saving throws is when they say they don't believe what they see, especially if they can give reasons why.

There are rare instances when the saving throw may automatically succeed or fail. There are times when the illusion created is either so perfect or so utterly fantastic as to be impossible even in a fantasy world. Be warned, these occasions are very rare and you should not expect your characters to benefit from them more than once or twice.

In many encounters, some party members will believe an illusion while others see it for what it really is. In these cases, revealing the truth to those deluded by the spell is not a simple matter of telling them. The magic of the spell has seized their minds. Considered from their point of view, they se a horrible monster (or whatever) while a friend is telling them it isn't real. They know magic can affect people's minds, but whose mind has been affected in this case? At best, having an illusion pointed out grants another saving throw with a +4 bonus.

Illusions do have other limitations. The caster must maintain a show of reality at all times when conducting an illusion. (If a squad of low-level fighters is created, the caster dictates their hits, misses, damage inflicted, apparent wounds, and so forth, and the referee decides whether the bounds of believability have been exceeded.) Maintaining an illusion normally requires concentration on the part of the caster, preventing him from doing other things. Disturb him and the illusion vanishes.

Illusions are spells of trickery and deceit, not damage and destruction. Thus, illusions cannot be used to cause real damage. When a creature is caught in the blast of an illusionary fireball or struck by the claws of an illusionary troll, he thinks he takes damage. The DM should record the illusionary damage (but tell the player his character has taken real damage). If the character takes enough damage to "die," he collapses in a faint. A system shock roll should be made for the character. (His mind, believing the damage to be real, may cause his body to cease functioning!) If the character survives, he regains consciousness after 1d3 turns with his illusionary damage healed. In most cases, the character quickly realizes that it was all an illusion.

When an illusion creates a situation of inescapable death, such as a giant block dropping from the ceiling, all those believing the illusion must roll for system shock. If they fail, they die--killed by the sheer terror of the situation. If they pass, they are allowed a new saving throw with a +4 bonus. Those who pass recognize the illusion for what it is. Those who fail faint for 1d3 turns.

Illusions do not enable characters to defy normal physical laws. An illusionary bridge cannot support a character who steps on it, even if he believes the bridge is real. An illusionary wall does not actually cause a rock thrown at it to bounce off. However, affected creatures attempt to simulate the reality of what they see as much as possible. A character who falls into an illusionary pit drops to the ground as if he had fallen. A character may lean against an illusionary wall, not realizing that he isn't actually putting his weight on it. If the same character were suddenly pushed, he would find himself falling through the very wall he thought was solid!

Illusions of creatures do not automatically behave like those creatures, nor do they have those creatures' powers. This depends on the caster's ability and the victim's knowledge of the creatures. Illusionary creatures fight using the caster's combat ability. They take damage and die when their caster dictates it. An illusory orc could continue to fight, showing no damage, even after it had been struck a hundred or a thousand times. Of course, long before this its attackers will become suspicious. Illusionary creatures can have whatever special abilities the caster can make appear (i.e., a dragon's fiery breath or a troll's regeneration), but they do not necessarily have unseen special abilities. There is no way a caster can create the illusion of a basilisk's gaze that turns people to stone. However, these abilities might be manifested through the fears of the victims. For example, Rath the fighter meets an illusionary basilisk. Rath has fought these beasties before and knows what they can do. His gaze accidentally locks with that of the basilisk. Primed by his own fears, Rath must make a system shock roll to remain alive. But if Rath had never seen a basilisk and had no idea that the creature's gaze could turn him to stone, there is no way his mind could generate the fear necessary to kill him. Sometimes ignorance is bliss!

Priest Spells

The spells of a priest, while sometimes having powers similar to those of the wizard, are quite different in their overall tone. The priest's role, more often than not, is as defender and guide for others. Thus, the majority of his spells work to aid others or provide some service to the community in which he lives. Few of his spells are truly offensive, but many can be used cleverly to protect or defend.

Like the wizard, the priest's level determines how many spells he retains. He must select these spells in advance, demonstrating his wisdom and far-sightedness by choosing those spells he thinks will be most useful in the trials that lurk ahead.

Unlike the wizard, the priest needs no spell book and does not roll to see if he learns spells. Priest spells are obtained in an entirely different manner. To obtain his spells, a priest must be faithful to the cause of his deity. If the priest feels confident in this (and most do), he can pray for his spells. Through prayer, the priest humbly and politely requests those spells he wishes to memorize. Under normal circumstances, these spells are then granted.

A priest's spell selection is limited by his level and by the different spheres of spells. (The spheres of influence, into which priest spells are divided, can be found under "Priests of a Specific Mythoi" in Chapter 3: player Character Classes.) Within the major spheres of his deity, a priest can use any spell of a given level when he is able to cast spells of that level. Thus, a druid is able to cast any 2nd-level plant sphere spells when he is able to cast 2nd-level spells. For spells belonging to the minor spheres of the priest's deity, he can cast spells only up to 3rd level. The knowledge of what spells are available to the priest becomes instantly clear as soon as he advances in level. This, too, is bestowed by his deity.

Priests must pray to obtain spells, as they are requesting their abilities from some greater power, be it their deity or some intermediary agent of this power. The conditions for praying are identical to those needed for the wizard's studying. Clearly then, it behooves the priest to maintain himself in good standing with this power, through word and deed. Priests who slip in their duties, harbor indiscreet thoughts, or neglect their beliefs, find that their deity has an immediate method of redress. If the priest has failed in his duties, the deity can deny him spells as a clear message of dissatisfaction. For minor infractions, the deity can deny minor spells. Major failings result in the denial of major spells or, even worse, all spells. These can be regained if the character immediately begins to make amends for his errors. Perhaps the character only needs to be a little more vigilant, in the case of a minor fault. A serious transgression could require special service, such as a quest or some great sacrifice of goods. These are things your DM will decide, should your character veer from the straight and narrow path of his religion.

Finally, your DM may rule that not all deities are equal, so that those of lesser power are unable to grant certain spells. If this optional rule is used, powers of demi-god status can only grant spells up to the 5th spell level. Lesser deities can grant 6th-level spells, while the greater deities have all spell levels available to them. You should inquire about this at the time you create your character (and decide which deity he worships), to prevent any unwelcome surprises later on.

Casting Spells

Both wizards and priests use the same rules for casting spells. To cast a spell, the character must first have the spell memorized. If it is not memorized, the spell cannot be cast. The caster must be able to speak (not under the effects of a silence spell or gagged) and have both arms free. (Note that the optional spell component rule [following section] can modify these conditions.) If the spell is targeted on a person, place, or thing, the caster must be able to see the target. It is not enough to cast a fireball 150 feet ahead into the darkness; the caster must be able to see the point of explosion and the intervening distance. Likewise, a magic missile (which always hits its target) cannot be fired into a group of bandits with the instruction to strike the leader; the caster must be able to identify and see the leader.

Once the casting has begun, the character must stand still. Casting cannot be accomplished while riding a roughly moving beast or a vehicle, unless special efforts are made to stabilize and protect the caster. Thus, a spell cannot be cast from the back of a galloping horse under any conditions, nor can a wizard or priest cast a spell on the deck of a ship during a storm. However, if the caster were below decks, protected from the wind and surging waves, he could cast a spell. While it is not normally possible to cast a spell from a moving chariot, a character who was steadied and supported by others could do so. Your DM will have to make a ruling in these types of extraordinary conditions.

During the round in which the spell is cast, the caster cannot move to dodge attacks. Therefore, no AC benefit from Dexterity is gained by spellcasters while casting spells. Furthermore, if the spellcaster is struck by a weapon or fails to make a saving throw before the spell is cast, the caster's concentration is disrupted. The spell is lost in a fizzle of useless energy and is wiped clean from the memory of the caster until it can be rememorized. Spellcasters are well advised not to stand at the front of any battle, at least if they want to be able to cast any spells!

Spell Components (Optional Rule)

When your character casts a spell, it is assumed that he is doing something to activate that spell. He may utter a few words, wave his hand around a couple of times, wiggle his toes, swallow a live spider, etc. But, under the standard rules, you don't have to know exactly what he does to activate the spell. Some of this can be answered if your DM uses the rules for spell components.

The actions required to cast a spell are divided into three groups: verbal, somatic (gestures), and material. Each spell description (found in Appendices 3 and 4) lists what combination of these components is needed to cast a spell. Verbal components require the caster to speak clearly (not be silenced in any way); somatic components require free gestures (thus, the caster cannot be bound or held); material components must be tossed, dropped, burned, eaten, broken, or whatever for the spell to work. While there is no specific description of the words and gestures that must be performed, the material components are listed in the spell descriptions. Some of these are common and easy to obtain. Others represent items of great value or scarcity. Whatever the component, it is automatically destroyed or lost when the spell is cast, unless the spell description specifically notes otherwise.

If the spell components optional rule is used in your campaign, your wizard or priest must have these items to cast the spell. Without them, he is helpless, even if the spell is memorized. For simplicity of play, it is best to assume that any spellcaster with any sense has a supply of the common items he is likely to need--wax, feathers, paint, sand, sticks, and fluff, for example. For expensive and rare items, it is perfectly proper for your DM to insist that special efforts be made to obtain these items. After all, you simply cannot assume your character has a valuable pearl handy whenever he needs one!

The three different aspects of spell components also change the conditions under which your character can cast his spells. No longer does he need to be able to speak, move, and use some item. He only needs to fulfill the required components. Thus, a spell with only a verbal component could be used by a naked, bound spellcaster. One requiring only gestures could be cast even within the radius of a silence spell. Most spells require a combination of components, but clever spellcasters often create new spells that need only a word or a gesture, enabling them to take their enemies by surprise.

Magical Research

One oft-ignored asset of both wizards and priests is magical research. While the spell lists for both groups offer a wide variety of tools and effects, the clever player character can quickly get an edge by researching his own spells. Where other spellcasters may fall quickly into tired and predictable patterns ("Look, it's a wizard! Get ready for the fireball, guys!"), an enterprising character can deliver sudden (and nasty) surprises!

Although your DM has the rules for handling spell research, there are some things you should know about how to proceed. First and foremost, research means that you and your DM will be working together to expand the game. This is not a job he does for you! Without your input, nothing happens. Second, whatever your character researches, it cannot be more powerful than the spells he is already able to cast. If it is, you must wait until your character can cast spells of an equal power. (Thus, as a 1st-level wizard, you cannot research a spell that is as powerful as a fireball. You must wait until your character can cast a fireball.) Finally, you will have to be patient and willing to have your character spend some money. He won't create the spell immediately, as research takes time. It also takes money, so you can expect your DM to use this opportunity to relieve your character of some of that excess cash. But, after all, how better for a spellcaster to spend his money?

Knowing these things, you should first write up a description of the spell you want to create. Be sure to include information on components, saving throws, range, duration, and all the other entries you find in the normal spell listings. When you give your DM the written description, tell him what you want the spell to do. (Sometimes what you write isn't really what you mean, and talking to your DM is a good way to prevent confusion.) After this, he will either accept or reject your spell. This is his choice and not all DMs will have the same answer. Don't kick and complain; find out what changes are needed to make the spell acceptable. You can probably iron out the differences.

Once all these things are done, your character can research the spell. Be ready for this to take some time. Eventually he will succeed, although the spell may not do quite what he expected. Your DM may revise the spell, perhaps reducing the area of effect or damage inflicted. Finally, all you have to do is name your spell. This should be something suitably pompous, such as "Delsenora's Malevolent Steamroller." After all, you want something to impress the locals!

Spell Descriptions

The spells are organized according to their group (priest or wizard) and level, listed in Appendices 3 and 4. Within each level, the spells are arranged alphabetically. At the start of each spell description is the following important game information:

Name: Each spell is identified by name. In parentheses after the name is the school (for wizard spells) to which that spell belongs. When more than one is listed, that spell is common to all schools given.

Some spells are reversible (they can be cast for an effect opposite to that of the standard spell). This is noted after the spell name. Priests with reversible spells must memorize the desired version. For example, a priest who desires a cause light wounds spell must petition for this form of the cure light wounds spell when meditating and praying. Note that severe penalties can result if the spell choice is at variance with the priest's alignment (possible penalties include denial of specific spells, entire spell levels, or even all spells for a certain period). The exact result (if any) depends on the reaction of the priest's patron deity, as determined by the DM.

Reversible wizard spells operate similarly. When the spell is learned, both forms are recorded in the wizard's spell books. However, the wizard must decide which version of the spell he desires to cast when memorizing the spell, unless the spell description specifically states otherwise. For example, a wizard who has memorized stone to flesh and desires to cast flesh to stone must wait until the latter form of the spell can be memorized (i.e., rest eight hours and study). If he could memorize two 6th-level spells, he could memorize each version once or one version twice.

School: In parentheses after the spell name is the name of the school of magic to which the spell belongs. For wizard spells, this defines which spells a wizard specialist can learn, depending on the wizard's school of specialization. For priest spells, the school notation is used only for reference purposes, to indicate which school the spell is considered to belong to, in case the DM needs to know for spell resistance (for example, elves' resistance to charm spells).

Sphere: This entry appears only for priest spells and identifies the sphere or spheres into which that spell falls.

Range: This lists the distance from the caster at which the spell effect occurs or begins A "0" indicates the spell can be used on the caster only, with the effect embodied within or emanating from him. "Touch" means the caster can use the spell on others if he can physically touch them. Unless otherwise specified, all other spells are centered on a point visible to the caster and within the range of the spell. The point can be a creature or object if desired. In general, a spell that affects a limited number of creatures within an area affects those closest to the center of the area first, unless there are other parameters operating (such as level or Hit Dice). Spells can be cast through narrow openings only if both the caster's vision and the spell energy can be directed simultaneously through the opening. A wizard standing behind an arrow slit can cast through it; sending a fireball through a small peephole he is peering through is another matter.

Components: This lists the category of components needed, V for verbal, S for somatic, and M for material. When material components are required, these are listed in the spell description. Spell components are expended as the spell is cast, unless otherwise noted. Priest holy symbols are not lost when a spell is cast. For cases in which material components are expended at the end of the spell (free action, shapechange, etc.), premature destruction of the components ends the spell.

Duration: This lists how long the magical energy of the spell lasts. Spells of instantaneous duration come and go the moment they are cast, although the results of these spells may be permanent and unchangeable by normal means. Spells of permanent duration last until the effects are negated by some means, usually by a dispel magic. Some spells have a variable duration. In most cases, the caster cannot choose the duration of spells. Spells with set durations (for example, 3 rounds/level) must be kept track of by the player. Spells of variable duration (for example, 3 + 1d4 rounds) are secretly rolled and recorded by the DM. Your DM may warn you when spell durations are approaching expiration, but there is usually no sign that a spell is going to expire; check with your DM to determine exactly how he handles this issue.

Certain spells can be ended at will by the caster. In order to dismiss these spells, the original caster must be within range of the spell's center of effect--within the same range at which the spell can be cast. The caster also must be able to speak words of dismissal. Note that only the original caster can dismiss his spells in this way.

Casting Time: This entry is important, if the optional casting time rules are used. If only a number is given, the casting time is added to the caster's initiative die rolls. If the spell requires a round or number of rounds to cast, it goes into effect at the end of the last round of casting time. If Delsenora casts a spell that takes one round, it goes into effect at the end of the round in which she begins casting. If the spell requires three rounds to cast, it goes into effect at the end of the third round. Spells requiring a turn or more go into effect at the end of the stated turn.

Area of Effect: This lists the creatures, volume, dimensions, weight, etc., that can be affected by the spell. Spells with an area or volume that can be shaped by the caster will have a minimum dimension of 10 feet in any direction, unless the spell description specifically states otherwise. Thus, a cloud that has a 10-foot cube per caster level might, when cast by a 12th-level caster, have dimensions 10' × 10' × 120', 20' × 20' × 30', or any similar combination that totals twelve 10-foot cubes. Combinations such as 5' × 10' × 240' are not possible unless specifically allowed.

Some spells (such as bless) affect the friends or enemies of the caster. In all cases, this refers to the perception of the caster at the time the spell is cast. For example, a chaotic good character allied with a lawful neutral cleric would receive the benefits of the latter's bless spell.

Saving Throw: This lists whether the spell allows the target a saving throw and the effect of a successful save: "Neg." results in the spell having no effect; "½" means the character suffers half the normal amount of damage; "none" means no saving throw is allowed.

Wisdom adjustments to saving throws apply to enchantment/charm spells.

Solid physical barriers provide saving throw bonuses and damage reduction. Cover and concealment may affect saving throws and damage (the DM has additional information about this).

A creature that successfully saves against a spell with no apparent physical effect (such as a charm, hold, or magic jar) may feel a definite force or tingle that is characteristic of a magical attack, if the DM desires. But the exact hostile spell effect or creature ability used cannot be deduced from this tingle.

A being's carried equipment and possessions are assumed to make their saving throws against special attacks if the creature makes its saving throw, unless the spell specifically states otherwise. If the creature fails its saving throw, or if the attack form is particularly potent, the possessions may require saving throws using either item saving throws (see the DMG) or the being's saving throw. The DM will inform you when this happens.

Any character can voluntarily forgo a saving throw. This allows a spell or similar attack that normally grants a saving throw to have full effect on the character. Likewise, any creature can voluntarily lower its magic resistance allowing a spell to automatically function when cast on it. Forgoing a saving throw or magic resistance roll need not always be voluntary. If a creature or character can be tricked into lowering its resistance, the spell will have full effect, even if it is not the spell the victim believed he was going to receive. The victim must consciously choose to lower his resistance; it is not sufficient that he is caught off guard. For example, a character would receive a saving throw if a wizard in the party suddenly attacked him with a fireball, even if the wizard had been friendly to that point. However, the same character would not receive a saving throw if the wizard convinced him that he was about to receive a levitation spell but cast a fireball instead. Your DM will decide when NPCs have lowered their resistances. You must tell your DM when your character is voluntarily lowering his resistance.

Spell Description: The text provides a complete description of how the spell functions and its game effects. It covers most typical uses of the spell, if there are more than one, but cannot deal with every possible application players might find. In these cases, the spell information in the text should provide guidance on how to adjudicate the situation.

Spells with multiple functions enable the caster to select which function he wants to use at the time of casting. Usually a single function of a multiple-function spell is weaker than a single-function spell of the same level.

Spell effects that give bonuses or penalties to abilities, attack rolls, damage rolls, saving throws, etc., are not usually cumulative with each other or with other magic: the strongest single effect applies. For example, a fighter drinks a potion of giant strength and then receives the 2nd-level wizard spell strength. Only the strongest magic (the potion) is effective. When the potion's duration ends, however, the strength spell is still in effect, until its duration also expires.