Medieval Miners Perils

In the gloomy depths of the medieval mines, miners were convinced that they were never alone-that malevolent demons and eerie gnomes lurked in the labyrinthine tunnels alongside other dark and unnamed horrors. While some of these subterranean spirits appeared harmless, their actions belied an unsettling intensity. They seemed to be ceaselessly excavating ore, yet mysteriously, the veins never diminished. These uncanny beings, sensitive to mockery, would retaliate by hurling stones at any miner audacious enough to taunt them.

Yet more sinister were the invisible entities, whose ghostly knocking sounds reverberated throughout the tunnels, filling the hearts of miners with dread. Then there were those malevolent specters that demanded ritualistic offerings, guarding their cherished ore veins with a zealousness that suggested consequences too dire to contemplate for those who dared to dig without appeasing them first.

In the chilling underworld of the mines, the penalty for ignoring these spiritual demands was swift and merciless. Those who dared to defy the spirits by withholding offerings were invariably met with a grim fate-either plummeting to their death down an abyssal shaft, being swallowed by the earth in a catastrophic cave-in, or falling victim to some other unspeakable calamity that lurked in the shadowy recesses. Yet, paradoxically, these same spirits would guide the benevolent and generous to untold riches hidden within the earth. In the realm of D&D, such capricious entities might manifest as pech, booka, or subterranean pixies.

But it was the more malevolent beings that truly chilled miners to their bones. The kobolds were the stuff of mining nightmares-small but malevolent figures thought to be nearly impossible to eradicate from the tunnels. Legend had it that these insidious beings reveled in sabotaging elevators, sending unwitting miners plummeting into the abyss below. Furthermore, miners believed that these mischievous kobolds were master tricksters, substituting precious silver veins with cobalt-a worthless, gray metal that would later find uses in alloys and paints. This deceptive switch left many a miner cursing the darkness, and forever questioning the very ground upon which they tread.

Mine Dusts

In the shadowy recesses of the mines, an insidious menace awaited in the form of fatal ants and solifugae-microscopic spiders with a venom so potent it could incapacitate even the most seasoned miners. A chilling belief prevailed among those who dared to venture into these subterranean mazes: each mine harbored its own distinct species of venomous critters. The poison they carried spread like wildfire through the veins, rendering its victims helpless and in excruciating pain.

Adding to the tension, lore whispered of a single antidote-a hidden hot spring tucked away in the heart of the very mine that housed these malevolent creatures. This mystical wellspring of healing water was the subject of many a miner's desperate search, its existence elevating the level of peril in the already-dangerous underground passages. Dungeon Masters might relish the opportunity to weave this elusive fountain into their unfolding narratives, adding yet another layer of urgency and suspense to the labyrinthine underworld.

The rocks and soils that miners dig can kill them, too - and it does so in real life. Ordinary dust scars the windpipe and causes lung diseases in old age. Other powders corrode the lungs at once, and Agricola reported that in the Carpathian mountains most women married at least seven husbands, as one by one each man smothered underground. A black dirt called pompholyx settled in open wounds and ate them to the bone.

It also destroyed iron, so wooden tools were used in the mines it infested. Cadmia dust does even more harm; it can burn into uninjured skin when moistened. A greenish metal called kobelt was said to devour the feet of men who walked over it. This was the origin of the word "kobold," because people assumed that little goblins laid kobelt traps on purpose. Miners protected themselves from these dusts with sealed leather coveralls and breathing masks made of animal bladders.

Poisonous dusts like pompholyx do no harm to healthy characters, but they infect any wound that is not bound within one round after contact. Pompholyx causes 1 hp damage per round to such open wounds until half again as much damage is taken as the character originally suffered. Any iron exposed to pompholyx (including armor) must save vs. acid every hour or be damaged. Armor loses one armor class of protection; weapons suffer a - 1 on damage rolls, and small items break. Intelligent enchanted swords plead not to be exposed to pompholyx.

Cadmia dust (metal powder dust) causes 1-4 hp damage per round, or 1-8 hp damage if the victim has wet skin. Kobelt destroys boots after 1-10 turns (if not brushed off) and causes 1 hp damage per round to bare feet. When characters stand on kobelt without shoes, they must save vs. poison (DC relative to exposure) or be unable to stand thereafter until their wounds are healed, otherwise falling to the ground in the kobelt for 1-10 hp damage. Kobelt might also be green slime.

Protective clothing prevents damage from dusts, but such clothing is useless once perforated. Whenever a PC suffers damage, he must make a dexterity check on 1d20 to protect his suit (DC relative to exposure).

People who get any corrosive dust in their eyes (for whatever reason) must save vs. poison or go blind (rolling a natural 1 on a 1d20, or not beating a DC of 14, temporarily for 3 minutes if immediately washed out with water, else 1 hour). Dusts have a 20% chance of affecting both of a person's eyes even if only one eye is exposed, due to sympathetic eye syndrome.

Dangerous Fumes

Navigating the mines was like playing a treacherous game with Death itself-where even the air you breathed could betray you. Stagnant pockets of air could be ventilated with pumps, but lurking in the gloom were far deadlier threats: insidious, poisonous gases that stole lives without warning.

Ingenious methods were deployed for detection; candles, when burned, shifted colors in the presence of certain noxious fumes, while canaries served as tragic sentinels, their tiny lives sacrificed in the detection of lethal methane gas. Using open flame to test for methane was a gamble of the highest stakes, a dance on the edge of a blade-do it wrong, and you'd trigger a cataclysmic explosion.

And yet, the very techniques used to crack open the bountiful veins of ore were also the breeding ground for an ever-present danger: carbon monoxide. Workmen would light underground bonfires, filling the rocky chambers with heat to expand and then crack the stubborn rock with the shocking chill of cold water.

This primal dance of fire and water, though essential, produced the gas as a deadly byproduct. Every time the miners struck flint to steel, they knew they were flirting with an invisible reaper-hoping their precautions would be enough to keep it at bay, but knowing that a single misstep could summon it forth.

Miners usually did this chore on one day, evacuated their tunnels, and did not return until 2+ days later. Some smoke settled on water, forming an arsenic film that floated into the air when the pools were disturbed. Those who survived the fumes reported that their limbs swelled until their hands and feet were spherical. Agricola reported watching men climb ladders to escape arsenic gas, only to fall as their fingers grew too bloated to grip the rungs.

Sulfurous fumes, present with volcanic activity, suffocate victims as if there were no oxygen in the air. Carbon monoxide smothers any character in only 1-3 rounds because of its potent poisons: Anyone exposed to arsenic gases must save vs. poison (DC 8); if the roll fails, they are immobilized by swelling.

Arsenic also smothers victims as if it were carbon monoxide. When this material settles in pools, characters can walk past safely. However, when anything disturbs the water, gas is released. If a character actually touches the water, they must save at -3 against a DC 11 or be paralyzed and begin to choke. Furthermore, anything wetted with arsenic-tainted water exudes poisonous gas in a 10' radius until it is scrubbed.

Some PCs may want to use these chemicals against enemies. If so, the DM should remember the dangers of carrying these poisons and being caught in one's own gas. None of the gases but arsenic have any effect aboveground in open air. Even inside buildings, they disperse too quickly to kill most people, given an open window or two.

The corrosive dusts cannot cause full damage except when concentrated. A few handfuls of kobelt or cadmia should be treated like the acid. Pompholyx cannot harm living things aboveground. PCs might use it to sabotage iron objects, but it would have to be applied directly and allowed to sit undisturbed for one hour.

Dig Out of Mines

In the perilous world of mining, the ever-looming specter of disaster is the catastrophic collapse of the earth itself. In the fantastical realms of D&D campaigns, the mathematics of survival are harsh yet clear: Tunnels must be reinforced with timbers or stone at intervals no greater than every 10 feet. Constructing these vital pillars of safety isn't a trivial task-it demands four man-hours of grueling labor for each support.

And that assumes you've already solved the logistical nightmares of sourcing the wood or stone and then hauling it down into the bowels of the earth, where darkness swallows all hope and the walls themselves seem to press in on you.

Even with these safeguards, the mine is a living, breathing entity of risk. With every pickaxe strike and every torch flicker, there's a haunting 2% chance per day that somewhere in that labyrinthine maze, the earth will give way, trapping or crushing anyone unfortunate enough to be in its path. Without these supports? Those odds skyrocket, and each passing moment becomes a roll of the dice with fate.

There's a staggering 10% chance per turn that a tunnel, once thought to be secure, will collapse in a roar of falling stone and a cloud of choking dust. It's as if the very walls of the mine are an ever-changing puzzle, constantly reshuffling, and a single wrong move could spell your doom.

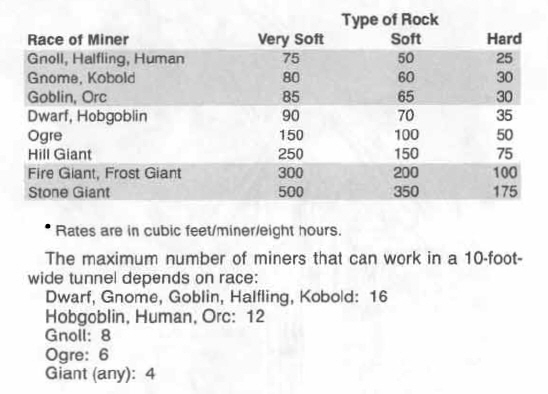

The DM should decide where the cave-in occurs, placing it wherever miners have weakened the ceiling most recently. Damage from falling rocks. Even if cave-ins miss characters entirely, they may trap the PCs underground. Below shows how fast rescuers can dig. Victims may try to scoop their way out, but unless they have picks and shovels, they dig at one-quarter the usual rate.

Read more about mines in Dungeons & Dragons.