In the heart of every dwarf lies an unbreakable connection to the deep and echoing mines. As the venerable Agricola once declared, the discovery of ore and the relentless pursuit of digging it up stand as paths to untold riches, rivaling the glittering treasures of legend. The thrill of striking a vein of precious metal is an intoxication, a passion that burns bright in the stout hearts of dwarvenkind.

But mines are more than mere sources of wealth; they are labyrinths of mystery and danger, hidden realms that beckon the bold and the curious. They transform into ideal "dungeons," where the shadows hide more than just rock and earth. Adventurers, those restless souls with a hunger for the unknown, find themselves drawn to these subterranean mazes. Abandoned tunnels whisper tales of ancient secrets, while active shafts resonate with the echoes of foes or nightmarish creatures lurking below.

Every strike of a pick, every glimmer of a gem, tells a story. It's a symphony of ambition, courage, and the insatiable desire to uncover what lies beneath. In the mines, darkness holds not only the promise of wealth but also the allure of adventure. For those brave enough to explore them, the mines offer gateways to worlds uncharted, where the line between fortune and folly is as thin as a miner's hope, and the pulse of the earth itself guides the way.

Mages can research spells or develop items to find ore, using the items de-scribed above as guidelines. Of course, all magic flirts with peril. New spells might invoke the elemental plane of Earth, and powerful but miscast spells could unleash volcanoes, earthquakes, or malign beings from other planes.

Despite their lore, prospectors depend on luck. Some mines begin in farmers' fields when plows turn up metallic stones. Other veins are found after landslides or earthquakes, and once a wildfire melted ore near the grounds surface, causing rivulets of gold to trickle down a mountainside.

Humans did not practice scientific geol-ogy until the 19th century. However, in a fantasy world, different races may be intimately familiar with the patterns of ore placement underground. Drow and svirfneblin, among others, certainly know where the earth hides its metals. Prospectors might venture underground to beg the advice of such races, but might eventually fight these races bitterly. Surface and underworld miners often clash because each group desires the same resources. PCs digging down into ore beds might meet beings chipping their way up.

Deep-dwelling races know that the earth is formed in layers of stone and dirt, with new layers forming over the old. Veins of ore usually appear where something disrupts these layers, concentrating minerals in one place. For example, magma can squeeze its way into other stones, carrying ore with it. It forms vertical dikes, horizontal sills, blister like laccoliths, and vast, rippling batholiths. Diamonds collect in kimberlite pipes, cones of volcanic rocks that project upward. Tectonic plates also alter the geology of an area. A rising plate might lift metals or oil, creating a chain of ‚deposits along the edge of a continent.

Underground peoples might also know about oil. Petroleum collects where the layers of earth curve, forming a trough or a trap for it. Petroleum is likely the "flaming oil" adventurers hurl at monsters; the only oils in the Middle Ages came from animal or vegetable fat and were unsuitable as weapons. Perhaps fantasy warriors import their oil from the underworld. Dungeon explorers may grow rich trading in oil they recover. Petroleum deposits might also interest Oriental characters; the ancient Chinese drilled for oil and salt water with bamboo derricks. Some Chinese emperors tried to tax these wells, but rural landlords resisted by posting scouts who dismantled the drills before inspectors arrived.

Once prospectors discover a vein, they must evaluate it by assaying (testing) the ore. Miners often judged unknown ores by chewing them. They also suspended earth in water so it could be studied with color-changing slips of paper, like the litmus paper used by modern chemists. Roman craftsmen made this paper by dipping parchment in shoe-black. It turned green when exposed to vitriol, a sulfate often found with metallic ores.

When these tests seem promising, assayers then heated ore in crucibles. Pure metals melt smoothly and at precise temperatures. Medieval assayers used flammable compounds to measure the melting points of ores. The craftsmen knew the temperature at which the powdered compounds would, combust, so if a molten metal ignited them, that showed how hot the metal was. These tests also helped miners choose fluxes for smelting. Fluxes are substances that aid the separation of slag from pure metal in the smelting process. Different colors of smoke created during these tests suggested different chemicals for use as fluxes, and deep purple smoke meant that the ore needed no flux at all. Each such test had to be performed in a cupel, or dish of ashes. The ashes were especially pure so they did not absorb the metal. Assayers preferred ash burned from beech or other trees that grow slowly.

Experts on metallurgy did more than test mines. They hunted counterfeiters and set values for metals. Grossly adulterated gold (used in forged coins or as part of a fake gold-mine scam) turns black in a candle flame. More sophisticated counterfeit metals appear real but will not melt until treated with lead flux. Once an assayer determined that a metal was genuine, he tested it with a touchstone to reveal its purity. The sample was beaten into a needle shape and scratched against black slate until it left a streak. By looking at the mark, a learned metallurgist could determine the ratio of metals in any alloy.

The tools required for assaying cost 50 gp, more if pure ashes are unavailable. DMs should make this check in secret. If the character succeeds, he learns the exact purity of the ore or coin being tested.

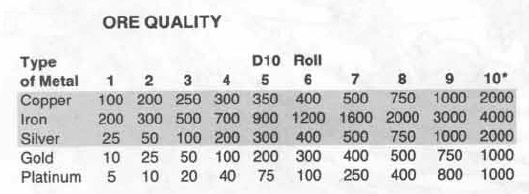

Ore Quality:

If the check fails, the assayer believes that the mine is either far more or far less valuable than it really is (there is a 50% chance of either result). PCs might then abandon a priceless mine or be convinced that a mine should be producing more than it does (and thus conclude that their workers are stealing ore).