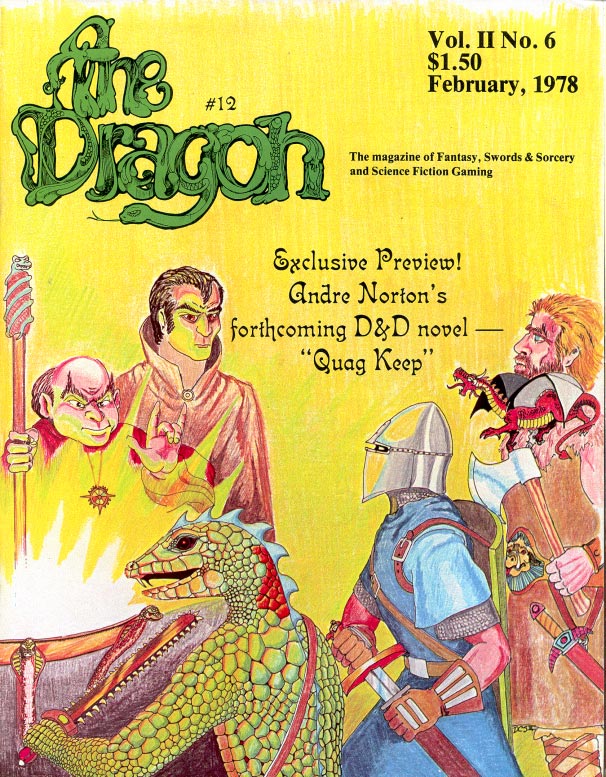

In February 1978, the sixth issue of the second volume of The Dragon magazine hit the stands, priced at a modest $1.50, offering a treasure trove of fantasy, swords and sorcery, and science fiction gaming content that would ignite the imaginations of tabletop enthusiasts everywhere. Published by TSR Hobbies, Inc., this magazine served as a beacon for players of Dungeons & Dragons and other role-playing games, delivering a mix of rules variants, fiction, humor, and tantalizing previews that promised to expand the boundaries of their gaming worlds. For those who lived for the clatter of dice and the thrill of epic quests, this issue was a call to adventure, packed with material that could transform a simple gaming session into a saga worthy of legend.

The cover alone hinted at the riches within, proclaiming an exclusive preview of Andre Norton's forthcoming D&D novel, Quag Keep, a tantalizing tease for fans of both literature and gaming. Norton, a titan of fantasy and science fiction, was venturing into the realm of Dungeons & Dragons with a story that would blend her narrative prowess with the game's iconic setting. While the preview itself was not detailed in the pages, the mere mention of Quag Keep was enough to set tongues wagging and minds racing, imagining how Norton's tale might weave the familiar elements of D&D -- wizards, warriors, and treacherous dungeons -- into a novel that could stand alongside the game's rulebooks as a source of inspiration.

Beyond this literary lure, the magazine offered a wealth of practical gaming content, starting with Leon Wheeler's whimsical exploration of "The More Humorous Side of D&D, or, 'They Shoot Hirelings, Don't They?'" Wheeler's piece delved into the unintentional comedy that often erupts during dungeon expeditions, a nod to the hapless hirelings who serve as cannon fodder for players' grand schemes. His writing captured the chaotic hilarity of a game where plans go awry, dice betray, and the lowly torchbearer meets a grim yet laughable fate. It was a reminder that D&D wasn't just about heroic triumphs but also about the absurdities that make every session memorable -- a perfect blend of levity for veterans and a siren call for newcomers eager to experience this unpredictable fun firsthand.

For those craving deeper mechanics, Rafael Ovalle's "A New Look at Illusionists" provided a robust variant for the D&D illusionist class, reimagining it as a specialist in deception and sensory trickery. Ovalle argued that illusionists, unlike their magic-user counterparts, wielded spells of lower level due to their focused expertise, yet possessed unique abilities like discerning illusionist-cast spells from those of other casters. His system introduced a 7% per level chance to spot disguised creatures or polymorphed objects, adding a layer of intrigue to encounters with rakshasas or leprechauns. The article detailed spell tables from first to seventh level, including new interpretations like "Gaze Reflection," which could bounce visual spells back at foes, and "Basilisk Gaze," turning enemies to stone with a stare. Ovalle's illusionists couldn't hurl fireballs, but their arsenal of hypnotic patterns and shadow magic offered cunning alternatives, making them a treacherous delight to play. This variant wasn't just a tweak -- it was a full-blown invitation to rethink strategy and embrace the art of misdirection, compelling readers to grab their dice and test these crafty spellcasters in their next campaign.

Jerome Arkenberg's "The Persian Mythos" took a different tack, plunging into the dualistic cosmology of Zoroastrianism to enrich D&D's pantheon. Here, the forces of Good, led by Ahura Mazda, clashed with the Evil of Ahriman and his Archdemons, offering a ready-made framework for epic battles between Law and Chaos. Ahura Mazda, the Wise Lord, boasted unlimited hit points and spells, a godlike figure clad in a star-decked robe, his throne perched in celestial light. His Archangels -- Vohu Manah, Asha, Kshathra Vairya, Armaiti, Haurvatat, and Ameretat -- each brought distinct powers, from protecting animals to smiting fiends, all statted with armor class 2 and wizardly might at 20th level. On the flip side, Ahriman's Archdemons, like Aeshma of Fury and the serpent Azi Dahaka, promised terrifying foes with claws, venom, and necromantic prowess. Arkenberg's mythos wasn't just flavor -- it was a toolkit for dungeon masters to craft campaigns steeped in ancient Persian lore, urging readers to pit their heroes against these divine and demonic titans in a struggle for the fate of worlds.

The fiction section delivered a gripping excerpt from Quag Keep itself, penned by Andre Norton, though only a fragment appeared in these pages. Titled "Geas Bound," it introduced a band of adventurers -- Milo the swordsman, Naile Fangtooth the berserker, Ingrge the elf, Yevele the thief, and others -- summoned from their mundane lives into the D&D world of Greyhawk by a mysterious force. The wizard Hystaspes revealed their predicament: bracelets with spinning dice dictated their fates, a geas binding them to seek and destroy an unknown entity threatening to merge their reality with Greyhawk's. Norton's prose crackled with tension as the characters grappled with dual identities and a quest they couldn't refuse, their dice rolling of their own accord to shape their destiny. The cliffhanger ending -- "THE END?" -- left readers ravenous for the full novel, while the promise of seeking Lichis, the Golden Dragon, hinted at epic confrontations to come. This snippet alone was a masterstroke, merging the game's mechanics with narrative stakes, and it beckoned players to imagine their own characters thrust into such a fantastical plight.

On the commercial front, the magazine brimmed with advertisements that doubled as gateways to further adventure. Ral Partha Enterprises showcased their 25mm fantasy miniatures -- Land Dragons, Witches, Sprite War Bands, and Armored Centaurs -- perfect for bringing battlefields to life, with a catalog available for just 25 cents. TSR itself touted Dungeons & Dragons for $9.95, a six-issue subscription to The Dragon for $9.00, and a complete gaming catalog for $2.00, refundable with a $10.00 miniature order. The pièce de résistance was Star Empires, a $7.50 galactic conquest game by John Snider, promising hyperspace battles and starship design for the space-faring gamer. Meanwhile, Metagaming's The Fantasy Trip offered Melee ($2.95) and Wizard ($3.95), microgames of man-to-man and magical combat, expandable into a full role-playing system. These ads weren't mere sales pitches -- they were invitations to expand one's gaming arsenal, each product a potential spark for countless hours of play.

The issue closed with a nod to community engagement, teasing upcoming features like a Japanese Mythos, optional demon generation, and the results of a "Name that Monster" contest, alongside a call for entries in a second contest. An ad for the Spring Revel on April 1 and 2 in Lake Geneva, hosted by TSR for $3.00, promised a weekend of D&D and other games, cementing The Dragon's role as a hub for the gaming faithful. This blend of content -- rules, fiction, humor, and commerce -- made the magazine a pulsating heart of the hobby, each page a portal to new possibilities.

What made this issue of The Dragon so captivating was its sheer diversity, a smorgasbord of ideas that catered to every facet of the gaming experience. Wheeler's humor reminded players that laughter was as vital as loot, while Ovalle's illusionists offered a cerebral twist on spellcasting, turning battles into mind games. Arkenberg's Persian deities elevated the stakes, inviting dungeon masters to weave grand mythologies into their campaigns, and Norton's fiction bridged the gap between game and story, showing how dice could drive a narrative as gripping as any epic. The advertisements, meanwhile, dangled tangible treasures -- miniatures, rulebooks, and new games -- that could materialize those imagined worlds on the tabletop.

For the uninitiated, this magazine was a siren's song, whispering of a hobby where imagination reigned supreme, where a few dollars and a handful of dice could unlock realms of wonder. For veterans, it was a war chest, brimming with tools to refine their craft, from quirky hireling mishaps to cosmic showdowns with Ahriman's minions. The Dragon didn't just inform -- it inspired, daring its readers to push their games beyond the mundane, to craft tales of valor and trickery that would echo around the gaming table for years.

Consider the illusionist, standing amidst a dungeon's gloom, conjuring a phantasmal killer to terrify a band of orcs, or reflecting a basilisk's gaze to petrify it in its tracks. Picture a cleric invoking Asha's truth to banish a sorcerer's lies, or a fighter facing Azi Dahaka's venomous wrath, shield raised against a storm of claws. Imagine Milo and his geas-bound companions, dice spinning wildly, as they ride toward Lichis's mountain lair, their fate hanging on a roll they can only half-control. These are the moments The Dragon seeded in its readers' minds, urging them to pick up the magazine, devour its contents, and let their next session explode with creativity.

The February 1978 issue of The Dragon wasn't just a periodical -- it was a grimoire of gaming magic, a call to arms for adventurers of all stripes. Its pages pulsed with the spirit of high fantasy, where rules bent to imagination, and every article was a spark for a new campaign. Whether you were a dungeon master plotting a Persian-inspired epic, a player itching to test an illusionist's guile, or a dreamer lost in Norton's Greyhawk, this magazine promised to fuel your passion. At $1.50, it was a steal -- a key to unlock the boundless realms of swords, sorcery, and science fiction, waiting for you to claim it from TSR Hobbies in Lake Geneva. Grab it, read it, and let the dice fall where they may -- your next great adventure begins here.