After choosing your character's race, you select his character class. A character class is like a profession or career. It is what your character has worked and trained at during his younger years. If you wanted to become a doctor, you could not walk out the door and begin work immediately. First you would have to get some training. The same is true of character classes in the AD&D game. Your character is assumed to have some previous training and guidance before beginning his adventuring career. Now, armed with a little knowledge, your character is ready to make his name and fortune.

The character classes are divided into four groups according to general occupations: warrior, wizard, priest, and rogue. Within each group are several similar character classes. All classes within a group share the same Hit Dice, as well as combat and saving throw progressions. Each character class within a group has different special powers and abilities that are available only to that class. Each player must select a group for his character, then a specific class within that group.

Warrior Wizard Priest Rogue

Fighter Mage Cleric Thief

Ranger Illusionist Druid Bard

Paladin Other Other

Fighter, mage, cleric, and thief are the standard classes. They are historical and legendary archetypes that are common to many different cultures. Thus, they are appropriate to any sort of AD&D game campaign. All of the other classes are optional. Your DM may decide that one or more of the optional classes are not appropriate to his campaign setting. Check with your DM before selecting an optional character class.

To help you choose your character's class, each group and its subordinate classes are described briefly. The groups and classes are described in detail later in this chapter.

Warrior

There are three different classes within the warrior group: fighter, paladin, and ranger. All are well-trained in the use of weapons and skilled in the martial arts.

The fighter is a champion, swordsman, soldier, and brawler. He lives or dies by his knowledge of weapons and tactics. Fighters can be found at the front of any battle, contesting toe-to-toe with monsters and villains. A good fighter needs to be strong and healthy if he hopes to survive.

The paladin is a warrior bold and pure, the exemplar of everything good and true. Like the fighter, the paladin is a man of combat. However, the paladin lives for the ideals of righteousness, justice, honesty, piety, and chivalry. He strives to be a living example of these virtues so that others might learn from him as well as gain by his actions.

The ranger is a warrior and a woodsman. He is skilled with weapons and is knowledgeable in tracking and woodcraft. The ranger often protects and guides lost travelers and honest peasant-folk. A ranger needs to be strong and wise to the ways of nature to live a full life.

Wizard

The wizard strives to be a master of magical energies, shaping them and casting them as spells. To do so, he studies strange tongues and obscure facts and devotes much of his time to magical research.

A wizard must rely on knowledge and wit to survive. Wizards are rarely seen adventuring without a retinue of fighters and men-at-arms.

Because there are different types (or schools) of magic, there are different types of wizards. The mage studies all types of magic and learns a wide variety of spells. His broad range makes him well suited to the demands of adventuring. The illusionist is an example of how a wizard can specialize in a particular school of magic, illusion in this case.

Priest

A priest sees to the spiritual needs of a community or location. Two types of priests--clerics and druids--are described in the Player's Handbook. Other types can be created by the DM to suit specific campaigns.

The cleric is a generic priest (of any mythos) who tends to the needs of a community. He is both protector and healer. He is not purely defensive, however. When evil threatens, the cleric is well-suited to seek it out on its own ground and destroy it.

The druid class is optional; it is an example of how the priest can be adapted to a certain type of setting. The druid serves the cause of nature and neutrality; the wilderness is his community. He uses his special powers to protect it and to preserve balance in the world.

Rogue

The rogue can be found throughout the world, wherever people gather and money changes hands. While many rogues are motivated only by a desire to amass fortune in the easiest way possible, some rogues have noble aims; they use their skills to correct injustice, spread good will, or contribute to the success of an adventuring group.

There are two types of rogues: thieves and bards.

To accomplish his goals, for good or ill, the thief is a skilled pilferer. Cunning, nimbleness, and stealth are his hallmarks. Whether he turns his talent against innocent passers-by and wealthy merchants or oppressors and monsters is a choice for the thief to make.

The bard is also a rogue, but he is very different from the thief. His strength is his pleasant and charming personality. With it and his wits he makes his way through the world. A bard is a talented musician and a walking storehouse of gossip, tall tales, and lore. He learns a little bit about everything that crosses his path; he is a jack-of-all-trades but master of none. While many bards are scoundrels, their stories and songs are welcome almost everywhere.

Class Ability Score Requirements

Each of the character classes has minimum scores in various abilities. A character must satisfy these minimums to be of that class. If your character's scores are too low for him to belong to any character class, ask your DM for permission to reroll one or more of your ability scores or to create an entirely new character. If you desperately want your character to belong to a particular class but have scores that are too low, your DM might allow you to increase these scores to the minimum needed. However, you must ask him first. Don't count on the DM allowing you to raise a score above 16 in any case.

Table 13:

Class Ability Minimums

Character

Class Str Dex Con Int Wis Cha

Fighter 9 -- -- -- -- --

Paladin* 12 -- 9 -- 13 17

Ranger* 13 13 14 -- 14 --

Mage -- -- -- 9 -- --

Specialist* Var Var Var Var Var Var

Cleric -- -- -- -- 9 --

Druid* -- -- -- -- 12 15

Thief -- 9 -- -- -- --

Bard* -- 12 -- 13 -- 15

* Optional character class. Specialist includes illusionist.

The complete character class descriptions that follow give the specific, detailed information you need about each class. These are organized according to groups. Information that applies to the entire group is presented at the start of the section. Each character class within the group is then explained.

The descriptions use game terms that may be unfamiliar to you; many of these are explained in this text (or you may look the terms up in the Glossary).

Experience Points / Level / Prime Requisite

XP Measure what a character has learned and how he has improved his skill during the course of his adventures. Characters earn experience points by completing adventures and by doing things specifically related to their class. A fighter, for example, earns more experience for charging and battling a monster than does a thief, because the fighter's training emphasizes battle while the thief's emphasizes stealth and cleverness. Characters accumulate experience points from adventure to adventure. When they accumulate enough, they rise to the next level of experience, gaining additional abilities and powers. The experience level tables for each character group list the total, accumulated experience points needed to reach each level.

Some DMs may require that a character spend a certain amount of time or money training before rising to the next experience level. Your DM will tell you the requirements for advancement when the time comes.

Level is a measure of the character's power. A beginning character starts at 1st level. To advance to the next level, the character must earn a requisite number of experience points. Different character classes improve at different rates. Each increase in level improves the character's survivability and skills.

Prime Requisite is the ability score or scores that are most important to a particular class. A fighter must be strong and a wizard must be intelligent; their prime requisites, therefore, are Strength and Intelligence, respectively. Some character classes have more than one prime requisite. Any character who has a score of 16 or more in all his prime requisites gains a 10% bonus to his experience point awards.

Warrior

The warrior group encompasses the character classes of heroes who make their way in the world primarily by skill at arms: fighters, paladins, and rangers.

Warriors are allowed to use any weapon. They can wear any type of armor. Warriors get 1 to 10 (1d10) hit points per level and can gain a special Constitution hit point bonus that is available only to warriors.

The disadvantage warriors have is that they are restricted in their selection of magical items and spells.

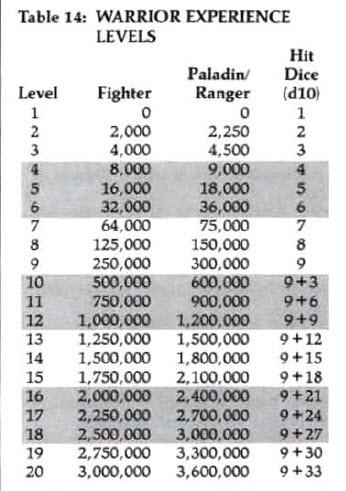

All warriors use Table 14 to determine their advancement in level as they earn experience points.

All warriors gain one 10-sided hit die per level from 1st through 9th. After 9th level, warriors gain just 3 hit points per level and they no longer gain additional hit point bonuses for high Constitution scores.

Table 14:

Warrior Experience Levels

All warriors gain the ability to make more than one melee attack per round as they rise in level. Table 15 shows how many melee attacks fighters, paladins, and rangers can make per round, as a function of their levels.

Table 15:

Warrior Melee Attacks per Round

Warrior Level Attacks/Round

1-6 1/round

7-12 3/2 rounds

13 & up 2/round

Fighter

Ability Requirements: Strength 9

Prime Requisite: Strength

Allowed Races: All

The principal attribute of a fighter is Strength. To become a fighter, a character must have a minimum Strength score of 9. A good Dexterity rating is highly desirable.

A fighter who has a Strength score (his prime requisite) of 16 or more gains a 10% bonus to the experience points he earns.

Also, high Strength gives the fighter a better chance to hit an opponent and enables him to cause more damage.

The fighter is a warrior, an expert in weapons and, if he is clever, tactics and strategy. There are many famous fighter from legend: Hercules, Perseus, Hiawatha, Beowulf, Siegfried, Cuchulain, Little John, Tristan, and Sinbad. History is crowded with great generals and warriors: El Cid, Hannibal, Alexander the Great, Charlemagne, Spartacus, Richard the Lionheart, and Belisarius. Your fighter could be modeled after any of these, or he could be unique. A visit to your local library can uncover many heroic fighters.

Fighters can have any alignment: good or evil, lawful or chaotic, or neutral.

As a master of weapons, the fighter is the only character able to have weapon specialization (explained in Chapter 5). Weapon specialization enables the fighter to use a particular weapon with exceptional skill, improving his chances to hit and cause damage with that weapon. A fighter character is not required to specialize in a weapon; the choice is up to the player. No other character class--not even ranger or paladin--is allowed weapon specialization.

While fighters cannot cast magical spells, they can use many magical items, including potions, protection scrolls, most rings, and all forms of enchanted armor, weapons, and shields.

When a fighter attains 9th level (becomes a "Lord"), he can automatically attract men-at-arms. These soldiers, having heard of the fighter, come for the chance to gain fame, adventure, and cash. They are loyal as long as they are well-treated, successful, and paid well. Abusive treatment or a disastrous campaign can lead to grumbling, desertion, and possibly mutiny. To attract the men, the fighter must have a castle or stronghold and sizeable manor lands around it. As he claims and rules this land, soldiers journey to his domain, thereby increasing his power. Furthermore, the fighter can tax and develop these lands, gaining a steady income from them. Your DM has information about gaining and running a barony.

In addition to regular men-at-arms, the 9th-level fighter also attracts an elite bodyguard (his "household guards"). Although these soldiers are still mercenaries, they have greater loyalty to their Lord than do common soldiers. In return, they expect better treatment and more pay than the common soldier receives. Although the elite unit can be chosen randomly, it is better to ask your DM what unit your fighter attracts. This allows him to choose a troop consistent with the campaign.

Table 16: Fighter's Followers

Roll percentile dice on each of the following subtables of Table 16: once for the leader of the troops, once for troops, and once for a bodyguard (household guards) unit.

Die

Roll Leader (and suggested magical items)

01-40 5th-level fighter, plate mail, shield, battle axe +2

41-75 6th-level fighter, plate mail, shield +1, spear +1, dagger +1

76-95 6th-level fighter, plate mail +1, shield, spear +1, dagger +1, plus 3rd-level fighter, splint mail, shield, crossbow of distance

96-99 7th-level fighter, plate mail +1, shield +1, broad sword +2, heavy war horse with horseshoes of speed

00 DM's Option

Die

Roll Troops/Followers (all 0th-level)

01-50 20 cavalry with ring mail, shield, 3 javelins, long sword, hand axe; 100 infantry with scale mail, polearm*, club

51-75 20 infantry with splint mail, morning star, hand axe; 60 infantry with leather armor, pike, short sword.

76-90 40 infantry with chain mail, heavy crossbow, short sword; 20 infantry with chain mail, light crossbow, military fork

91-99 10 cavalry with banded mail, shield, lance, bastard sword, mace; 20 cavalry with scale mail, shield, lance, long sword, mace; 30 cavalry with studded leather armor, shield, lance, long sword

00 DM's Option (Barbarians, headhunters, armed peasants, extra-heavy cavalry, etc.)

*Player selects type.

Die

Roll Elite Units

01-10 10 mounted knights; 1st-level fighters with field plate, large shield, lance, broad sword, morning star, and heavy war horse with full barding

11-20 10 1st-level elven fighter/mages with chain mail, long sword, long bow, dagger

21-30 15 wardens: 1st-level rangers with scale mail, shield, long sword, spear, long bow

31-40 20 berserkers: 2nd-level fighters with leather armor, shield, battle axe, broad

sword, dagger (berserkers receive +1 bonus to attack and damage rolls)

41-65 20 expert archers: 1st-level fighters with studded leather armor, long bows or crossbows (+2 to hit, or bow specialization, if using that optional rule)

66-99 30 infantry: 1st-level fighters with plate mail, body shield, spear, short sword

00 DM's Option (pegasi cavalry, eagle riders, demihumans, siege train, etc.)

The DM may design other tables that are more appropriate to his campaign. Check with your DM upon reaching 9th level.

A fighter can hold property, including a castle or stronghold, long before he reaches 9th level. However, it is only when he reaches this level that his name is so widely known that he attracts the loyalty of other warriors.

Paladin

Ability Requirements: Strength 12

Constitution 9

Wisdom 13

Charisma 17

Prime Requisites: Strength, Charisma

Races Allowed: Human

The paladin is a noble and heroic warrior, the symbol of all that is right and true in the world. As such, he has high ideals that he must maintain at all times. Throughout legend and history there are many heroes who could be called paladins: Roland and the 12 Peers of Charlemagne, Sir Lancelot, Sir Gawain, and Sir Galahad are all examples of the class. However, many brave and heroic soldiers have tried and failed to live up to the ideals of the paladin. It is not an easy task!

Only a human may become a paladin. He must have minimum ability scores of Strength 12, Constitution 9, Wisdom 13, and Charisma 17. Strength and Charisma are the prime requisites of the paladin. A paladin must be lawful good in alignment and must always remain lawful good. A paladin who changes alignment, either deliberately or inadvertently, loses all his special powers -- sometimes only temporarily and sometimes forever. He can use any weapon and wear any type of armor.

A paladin who has Strength and Charisma scores of 16 or more gains a 10% bonus to the experience points he earns.

Lawfulness and good deeds are the meat and drink of a paladin. If a paladin ever knowingly performs a chaotic act, he must seek a high-level (7th or more) cleric of lawful good alignment, confess his sin, and do penance as prescribed by the cleric. If a paladin should ever knowingly and willingly perform an evil act, he loses the status of paladinhood immediately and irrevocably. All benefits are then lost and no deed or magic can restore the character to paladinhood: He is ever after a fighter. The character's level remains unchanged when this occurs and experience points are adjusted accordingly. Thereafter the character is bound by the rules for fighters. He does not gain the benefits of weapon specialization (if this is used) since he did not select this for his character at the start.

If the paladin commits an evil act while enchanted or controlled by magic, he loses his paladin status until he can atone for the deed. This loss of status means the character loses all his special abilities and essentially functions as a fighter (without weapon specialization) of the same level. Regaining his status undoubtedly requires completion of some dangerous quest or important mission to once again prove his worth and assuage his own guilt. He gains no experience prior to or during the course of this mission, and regains his standing as a paladin only upon completing the quest.

A paladin has the following special benefits:

A paladin can detect the presence of evil intent up to 60 feet away by concentrating on locating evil in a particular direction. He can do this as often as desired, but each attempt takes one round. This ability detects evil monsters and characters.

A paladin receives a +2 bonus to all saving throws.

A paladin is immune to all forms of disease. (Note that certain magical afflictions --lycanthropy and mummy rot --are curses and not diseases.)

A paladin can heal by laying on hands. The paladin restores 2 hit points per experience level. He can heal himself or someone else, but only once per day.

A paladin can cure diseases of all sorts (though not cursed afflictions such as lycanthropy). This can be done only once per week for each five levels of experience (once per week at levels 1 through 5, twice per week at levels 6 through 10, etc.).

A paladin is surrounded by an aura of protection with a 10-foot radius. Within this radius, all summoned and specifically evil creatures suffer a -1 penalty to their attack rolls, regardless of whom they attack. Creatures affected by this aura can spot its source easily, even if the paladin is disguised.

A paladin using a holy sword projects a circle of power 10 feet in diameter when the sword is unsheathed and held. This power dispels hostile magic of a level up to the paladin's experience level. (A holy sword is a very special weapon; if your paladin acquires one, the DM will explain its other powers.)

A paladin gains the power to turn undead and fiends when he reaches 3rd level. He affects these monsters the same as does a cleric two levels lower--for example, at 3rd level he has the turning power of a 1st-level cleric. See the section on priests for more details on this ability.

A paladin may call for his war horse upon reaching 4th level, or anytime thereafter. This faithful steed need not be a horse; it may be whatever sort of creature is appropriate to the character (as decided by the DM). A paladin's war horse is a very special animal, bonded by fate to the warrior. The paladin does not really "call" the animal, nor does the horse instantly appear in front of him. Rather, the character must find his war horse in some memorable way, most frequently by a specific quest.

A paladin can cast priest spells once he reaches 9th level. He can cast only spells of the combat, divination, healing, and protective spheres. (Spheres are explained in the Priest section.) The acquisition and casting of these spells abide by the rules given for priests.

The spell progression and casting level are listed in Table 17. Unlike a priest, the paladin does not gain extra spells for a high Wisdom score. The paladin cannot cast spells from clerical or druidical scrolls nor can he use priest items unless they are allowed to the warrior group.

Table 17:

Paladin Spell Progression

Paladin Casting Priest Spell Level

Level Level 1 2 3 4

9 1 1 -- -- --

10 2 2 -- -- --

11 3 2 1 -- --

12 4 2 2 -- --

13 5 2 2 1 --

14 6 3 2 1 --

15 7 3 2 1 1

16 8 3 3 2 1

17 9* 3 3 3 1

18 9* 3 3 3 1

19 9* 3 3 3 2

20* 9* 3 3 3 3

* Maximum spell ability

A paladin may not possess more than 10 magical items. Furthermore, these may not exceed one suit of armor, one shield, four weapons (arrows and bolts are not counted), and four other magical items.

A paladin never retains wealth. He may keep only enough treasure to support himself in a modest manner, pay his henchmen, men-at-arms, and servitors a reasonable rate, and to construct or maintain a small castle or keep (funds can be set aside for this purpose). All excess must be donated to the church or another worthy cause. This money can never be given to another player character or NPC controlled by a player.

A paladin must tithe to whatever charitable, religious institution of lawful good alignment he serves. A tithe is 10% of the paladin's income, whether coins, jewels, magical items, wages, rewards, or taxes. It must be paid immediately.

A paladin does not attract a body of followers upon reaching 9th level or building a castle. However, he can still hire soldiers and specialists, although these men must be lawful good in comportment.

A paladin may employ only lawful good henchmen (or those who act in such a manner when alignment is unknown). A paladin will cooperate with characters of other alignments only as long as they behave themselves. He will try to show them the proper way to live through both word and deed. The paladin realizes that most people simply cannot maintain his high standards. Even thieves can be tolerated, provided they are not evil and are sincerely trying to reform. He will not abide the company of those who commit evil or unrighteous acts. Stealth in the cause of good is acceptable, though only as a last resort.

Ranger

Ability Requirements: Strength 13

Dexterity 13

Constitution 14

Wisdom 14

Prime Requisites: Strength, Dexterity, Wisdom

Races Allowed: Human, Elf, Half-elf

The ranger is a hunter and woodsman who lives by not only his sword, but also his wits. Robin Hood, Orion, Jack the giant killer, and the huntresses of Diana are examples of rangers from history and legend. The abilities of the ranger make him particularly good at tracking, woodcraft, and spying.

Table 18:

Ranger Abilities

Ranger Hide in Move Casting Priest Spell Levels

Level Shadows Silently Level 1 2 3

1 10% 15% -- -- -- --

2 15% 21% -- -- -- --

3 20% 27% -- -- -- --

4 25% 33% -- -- -- --

5 31% 40% -- -- -- --

6 37% 47% -- -- -- --

7 43% 55% -- -- -- --

8 49% 62% 1 1 -- --

9 56% 70% 2 2 -- --

10 63% 78% 3 2 1 --

11 70% 86% 4 2 2 --

12 77% 94% 5 2 2 1

13 85% 99%* 6 3 2 1

14 93% 99% 7 3 2 2

15 99%* 99% 8 3 3 2

16 99% 99% 9 3 3** 3

* Maximum percentile score

** Maximum spell ability

The ranger must have scores not less than 13 in Strength, 14 in Constitution, 13 in Dexterity, and 14 in Wisdom. The prime requisites of the ranger are Strength, Dexterity, and Wisdom. Rangers are always good, but they can be lawful, neutral, or chaotic. It is in the ranger's heart to do good, but not always by the rules.

A ranger who has Strength, Dexterity, and Wisdom scores of 16 or more gains a 10% bonus to the experience points he earns.

Although the ranger can use any weapon and wear any armor, several of his special abilities are usable only when he is wearing studded leather or lighter armor.

Although he has the basic skills of a warrior, the ranger also has several advantages. When wearing studded leather or lighter armor, a ranger can fight two-handed with no penalty to his attack rolls (see "Attacking with Two Weapons" in Chapter 9: Combat). Obviously, the ranger cannot use a shield when fighting this way. A ranger can still fight with two weapons while wearing heavier armor than studded leather, but he suffers the standard attack roll penalties.

The ranger is skilled woodsman. Even if the optional proficiency rules are not used, the ranger has tracking proficiency. If the proficiency rules are used in your campaign, the ranger knows tracking without expending any points. Furthermore, this skill improves by +1 for every three levels the ranger has earned (3rd to 5th level, +1; 6th to 8th level, +2, etc.). While wearing studded leather or lighter armor, the ranger can try to move silently and hide in shadows. His chance to succeed in natural surroundings is given on Table 18 (modified by the ranger's race and Dexterity, as given on Tables 27 and 28). When attempting these actions in non-natural surroundings (a musty crypt or city streets) the chance of success is halved. Hiding in shadows and moving silently are not possible in any armor heavier than studded leather--the armor is inflexible and makes too much noise.

In their roles as protector of good, rangers tend to focus their efforts against some particular creature, usually one that marauds their homeland. Before advancing to 2nd level, every ranger must select a species enemy. Typical enemies include giants, orcs, lizard men, trolls, or ghouls; your DM has final approval on the choice. Thereafter, whenever the ranger encounters that enemy, he gains a +4 bonus to his attack rolls. This enmity can be concealed only with great difficulty, so the ranger suffers a -4 penalty on all encounter reactions with creatures of the hated type. Furthermore, the ranger will actively seek out this enemy in combat in preference to all other foes unless someone else presents a much greater danger.

Rangers are adept with both trained and untamed creatures, having a limited degree of animal empathy. If a ranger carefully approaches or tends any natural animal, he can try to modify the animal's reactions. (A natural animal is one that can be found in the real world -- a bear, snake, zebra, etc.)

When dealing with domestic or non-hostile animals, a ranger can approach the animal and befriend it automatically. He can easily discern the qualities of the creature (spotting the best horse in the corral or seeing that the runt of the litter actually has great promise).

When dealing with a wild animal or an animal trained to attack, the animal must roll a saving throw vs. rods to resist the ranger's overtures. (This table is used even though the ranger's power is non-magical.) The ranger imposes a -1 penalty on the die roll for every three experience levels he has earned (-1 at 1st to 3rd, -2 at 4th to 6th, etc.). If the creature fails the saving throw, its reaction can be shifted one category as the ranger chooses. Of course, the ranger must be at the front of the party and must approach the creature fearlessly.

For example, Beornhelm, a 7th-level ranger, is leading his friends through the woods. On entering a clearing, he spots a hungry black bear blocking the path on the other side. Signaling his friends to wait, Beornhelm approaches the beast, whispering soothing words. The DM rolls a saving throw vs. rods for the bear, modified by -3 for Beornhelm's level. The bear's normal reaction is unfriendly, but Beornhelm's presence reduces this to neutral. The party waits patiently until the bear wanders off to seek its dinner elsewhere.

Later, Beornhelm goes to the horse market to get a new mount. The dealer shows him a spirited horse, notorious for being vicious and stubborn. Beornhelm approaches it carefully, again speaking soothingly, and mounts the stallion with no difficulty. Ridden by Beornhelm, the horse is spirited but well-behaved. Approached by anyone else, the horse reverts to its old ways.

A ranger can learn priest spells, but only those of the plant or animal spheres (see "Priest" later in this chapter), when he reaches 8th level (see Table 18). He gains and uses his spells according to the rules given for priests. He does not gain bonus spells for a high Wisdom score, nor is he ever able to use priest scrolls or magical items unless specially noted otherwise.

Rangers can build castles, forts, or strongholds, but do not gain any special followers by doing so.

At 10th level, a ranger attracts 2d6 followers. These followers might be normal humans, but they are often animals or even stranger denizens of the land. Table 19 can be used to determine these, or your DM may assign specific followers.

Table 19:

Ranger's Followers

Die

Roll Follower

01-10 Bear, black

11-20 Bear, brown

21 Brownie*

22-26 Cleric (human)

27-38 Dog/wolf

39-40 Druid

41-50 Falcon

51-53 Fighter (elf)

54-55 Fighter (gnome)

56-57 Fighter (halfling)

58-65 Fighter (human)

66 Fighter/mage (elf)*

67-72 Great cat (tiger, lion, etc.)*

73 Hippogriff

74 Pegasus*

75 Pixie*

76-80 Ranger (half-elf)

81-90 Ranger (human)

91-94 Raven

95 Satyr*

96 Thief (halfling)

97 Thief (human)

98 Treant*

99 Werebear/weretiger*

00 Other wilderness creature (chosen by the DM)

*If the ranger already has a follower of this type, ignore this result and roll again.

Of course, your DM can assign particular creatures, either choosing from the list above or from any other source. He can also rule that certain creatures are not found in the region -- it is highly unlikely that a tiger would come wandering through a territory similar to western Europe!

These followers arrive over the course of several months. often they are encountered during the ranger's adventures (allowing you and your DM a chance to role-play the initial meeting). While the followers are automatically loyal and friendly toward the ranger, their future behavior depends on the ranger's treatment of them. In all cases, the ranger does not gain any special method of communicating with his followers. He must either have some way of speaking to them or they simply mutely accompany him on his journeys. ("Yeah, this bear's been with me for years. Don't know why--he just seems to follow me around. I don't own him and can't tell him to do anything he don't want to do," said the grizzled old woodsman sitting outside the tavern.)

Of course, the ranger is not obligated to take on followers. If he prefers to remain independent, he can release his followers at any time. They reluctantly depart, but stand ready to answer any call for aid he might put out at a later time.

Like the paladin, the ranger has a code of behavior.

A ranger must always retain his good alignment. If the ranger intentionally commits an evil act, he automatically loses his ranger status. Thereafter he is considered a fighter of the same level (if he has more experience points than a fighter of his level, he loses all the excess experience points). His ranger status can never be regained. If the ranger involuntarily commits an evil act (perhaps in a situation of no choice), he cannot earn any more experience points until he has cleansed himself of that evil. This can be accomplished by correcting the wrongs he committed, revenging himself on the person who forced him to commit the act, or releasing those oppressed by evil. The ranger instinctively knows what things he must do to regain his status (i.e., the DM creates a special adventure for the character).

Furthermore, rangers tend to be loners, men constantly on the move. They cannot have henchmen, hirelings, mercenaries, or even servants until they reach 8th level. While they can have any monetary amount of treasure, they cannot have more treasure than they can carry. Excess treasure must either be converted to a portable form or donated to a worthy institution (an NPC group, not a player character).

Wizard

The wizard group encompasses all spellcasters working in the various fields of magic--both those who specialize in specific schools of magic and those who study a broad range of magical theories. Spending their lives in pursuit of arcane wisdom, wizards have little time for physical endeavors. They tend to be poor fighters with little knowledge of weaponry. However, they command powerful and dangerous energies with a few simple gestures, rare components, and mystical words.

Spells are the tools, weapons, and armor of the wizard. He is weak in a toe-to-toe fight, but when prepared he can strike down his foes at a distance, vanish in an instant, become a wholly different creature, or even invade the mind of an enemy and take control of his thoughts and actions. No secrets are safe from a wizard and no fortress is secure. His quest for knowledge and power often leads him into realms where mortals were never meant to go.

Wizards cannot wear any armor, for several reasons. Firstly, most spells require complicated gestures and odd posturings by the caster and armor restricts the wearer's ability to do these properly. Secondly, the wizard spent his youth (and will spend most of his life) learning arcane languages, poring through old books, and practicing his spells. This leaves no time for learning other things (like how to wear armor properly and use it effectively). If the wizard had spent his time learning about armor, he would not have even the meager skills and powers he begins with. There are even unfounded theories that claim the materials in most armors disrupt the delicate fabric of a spell as it gathers energy; the two cannot exist side by side in harmony. While this idea is popular with the common people, true wizards know this is simply not true. If it were, how would they ever be able to cast spells requiring iron braziers or metal bowls?

For similar reasons, wizards are severely restricted in the weapons they can use. They are limited to those that are easy to learn or are sometimes useful in their own research. Hence, a wizard can use a dagger or a staff, items that are traditionally useful in magical studies. Other weapons allowed are darts, knives, and slings (weapons that require little skill, little strength, or both).

Wizards can use more magical items than any other characters. These include potions, rings, wands, rods, scrolls, and most miscellaneous magical items. A wizard can use a magical version of any weapon allowed to his class but cannot use magical armor, because no armor is allowed. Between their spells and magical items, however, wizards wield great power.

Finally, all wizards (whether mages or specialists) can create new magical items, ranging from simple scrolls and potions to powerful staves and magical swords. Once he reaches 9th level, a wizard can pen magical scrolls and brew potions. He can construct more powerful magical items only after he has learned the appropriate spells (or works with someone who knows them). Your DM should consult the Spell Research and Magical Items sections of the DMG for more information.

No matter what school of magic the wizard is involved in, Intelligence is his prime requisite (or one of several prime requisites). Characters must have an Intelligence score of at least 9 to qualify to be a wizard.

All wizards use Table 20 to determine their advancement in level as they earn experience points. They also use Table 21 to determine the levels and numbers of spells they can cast at each experience level.

All wizards gain one four-sided Hit Die (1d4) per level from 1st through 10th levels. After 10th level, wizards earn 1 hit point per level and they no longer gain additional hit point bonuses for high Constitution scores.

Table 20:

Wizard Experience Levels

Level Mage/Specialist Hit Dice (d4)

1 0 1

2 2,500 2

3 5,000 3

4 10,000 4

5 20,000 5

6 40,000 6

7 60,000 7

8 90,000 8

9 135,000 9

10 250,000 10

11 375,000 10+1

12 750,000 10+2

13 1,125,000 10+3

14 1,500,000 10+4

15 1,875,000 10+5

16 2,250,000 10+6

17 2,625,000 10+7

18 3,000,000 10+8

19 3,375,000 10+9

20 3,750,000 10+10

Table 21:

Wizard Spell Progression

Wizard Spell Level

Level 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

1 1 -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

2 2 -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

3 2 1 -- -- -- -- -- -- --

4 3 2 -- -- -- -- -- -- --

5 4 2 1 -- -- -- -- -- --

6 4 2 2 -- -- -- -- -- --

7 4 3 2 1 -- -- -- -- --

8 4 3 3 2 -- -- -- -- --

9 4 3 3 2 1 -- -- -- --

10 4 4 3 2 2 -- -- -- --

11 4 4 4 3 3 -- -- -- --

12 4 4 4 4 4 1 -- -- --

13 5 5 5 4 4 2 -- -- --

14 5 5 5 4 4 2 1 -- --

15 5 5 5 5 5 2 1 -- --

16 5 5 5 5 5 3 2 1 --

17 5 5 5 5 5 3 3 2 --

18 5 5 5 5 5 3 3 2 1

19 5 5 5 5 5 3 3 3 1

20 5 5 5 5 5 4 3 3 2

Learning and casting spells require long study, patience, and research. Once his adventuring life begins, a wizard is largely responsible for his own education; he no longer has a teacher looking over his shoulder and telling him which spell to learn next. This freedom is not without its price, however. It means that the wizard must find his own source for magical knowledge: libraries, guilds, or captured books and scrolls.

Whenever a wizard discovers instructions for a spell he doesn't know, he can try to read and understand the instructions. The player must roll percentile dice. If the result is equal to or less than the percentage chance to learn a new spell (listed on Table 4), the character understands the spell and how to cast it. He can enter the spell in his spell book (unless he has already learned the maximum number of spells allowed for that level). If this die roll is higher than the character's chance to learn the spell, he doesn't understand the spell. Once a spell is learned, it cannot be unlearned. It remains part of that character's repertoire forever. Thus, a character cannot choose to "forget" a spell so as to replace it with another.

A wizard's spell book can be a single book, a set of books, a bundle of scrolls, or anything else your DM allows. The spell book is the wizard's diary, laboratory journal, and encyclopedia, containing a record of everything he knows. Naturally, it is his most treasured possession; without it he is almost helpless.

A spell book contains the complicated instructions for casting the spell -- the spell's recipe, so to speak. Merely reading these instructions aloud or trying to mimic the instructions does not enable one to cast the spell. Spells gather and shape mystical energies; the procedures involved are very demanding, bizarre, and intricate. Before a wizard can actually cast a spell, he must memorize its arcane formula. This locks an energy pattern for that particular spell into his mind. Once he has the spell memorized, it remains in his memory until he uses the exact combination of gestures, words, and materials that triggers the release of this energy pattern. Upon casting, the energy of the spell is spent, wiped clean from the wizard's mind. The wizard cannot cast that spell again until he returns to his spell book and memorizes it again.

Initially the wizard is able to retain only a few of these magical energies in his mind at one time. Furthermore, some spells are more demanding and complex than others; these are impossible for the inexperienced wizard to memorize. With experience, the wizard's talent expands. He can memorize more spells and more complex spells. Still, he never escapes his need to study; the wizard must always return to his spell books to refresh his powers.

Another important power of the wizard is his ability to research new spells and construct magical items. Both endeavors are difficult, time-consuming, costly, occasionally even perilous. Through research, a wizard can create an entirely new spell, subject to the DM's approval. Likewise, by consulting with your DM, your character can build magical items, either similar to those already given in the rules or of your own design. Your DM has information concerning spell research and magical item creation.

Unlike many other characters, wizards gain no special benefits from building a fortress or stronghold. They can own property and receive the normal benefits, such as monthly income and mercenaries for protection. However, the reputations of wizards tend to discourage people from flocking to their doors. At best, a wizard may acquire a few henchmen and apprentices to help in his work.

Mage

Ability Requirements: Intelligence 9

Prime Requisite: Intelligence

Races Allowed: Human, Elf, Half-elf

Mages are the most versatile types of wizards, those who choose not to specialize in any single school of magic. This is both an advantage and disadvantage. On the positive side, the mage's selection of spells enables him to deal with many different situations. (Wizards who study within a single school of magic learn highly specialized spells, but at the expense of spells from other areas.) The other side of the coin is that the mage's ability to learn specialized spells is limited compared to the specialist's.

Mages have no historical counterparts; they exist only in legend and myth. However, players can model their characters after such legendary figures as Merlin, Circe, or Medea. Accounts of powerful wizards and sorceresses are rare, since their reputations are based in no small part on the mystery that surrounds them. These legendary figures worked toward secret ends, seldom confiding in the normal folk around them.

A mage who has an Intelligence score of 16 or higher gains a 10% bonus to the experience points he earns.

The Schools of Magic

Spells are divided into nine different categories, or schools, according to the types of magical energy they utilize. Each school has its own special methods and practices.

Although they are called schools, schools of magic are not organized places where a person goes to study. The word "school" identifies a magical discipline. A school is an approach to magic and spellcasting that emphasizes a particular sort of spell. Practitioners of a school of magic may set up a magical university to teach their methods to beginners, but this is not necessary. Many powerful wizards learned their craft studying under reclusive masters in distant lands.

The nine schools of magic are Abjuration, Alteration, Conjuration/Summoning, Enchantment/Charm, Greater Divination, Illusion, Invocation/Evocation, Necromancy, and Lesser Divination.

Table 22:

Wizard Specialist Requirements

Minimum

Ability

Specialist School Race Score Opposition School(s)

Abjurer Abjuration H 15 Wis Alteration & Illusion

Conjurer Conj./Summ. H, ½ E 15 Con Gr. Divin. & Invocation

Diviner Gr. Divin. H, ½ E, E 16 Wis Conj./Summ.

Enchanter Ench./Charm H, ½ E, E 16 Cha Invoc./Evoc. & Necromancy

Illusionist Illusion H, G 16 Dex Necro., Invoc./Evoc., Abjur.

Invoker Invoc./Evoc. H 16 Con Ench./Charm Conj./Summ.

Necromancer Necromancy H 16 Wis Illusion & Ench./Charm

Transmuter Alteration H, ½ E 15 Dex Abjuration & Necromancy

This diagram illustrates the schools that oppose each other. See Table 22 and its entry descriptions for more information.

Of these schools, eight are greater schools while the ninth, lesser divination, is a minor school. The minor school of lesser divination includes all divination spells of the 4th spell level or less (available to all wizards). Greater divinations are those divination spells of the 5th spell or higher.

Specialist Wizards

A wizard who concentrates his effort in a single school of magic is called a specialist. There are specialists in each type of magic, although some are extremely rare. Not all specialists are well-suited to adventuring--the diviner's spells are limited and not generally useful in dangerous situations. On the other hand, player characters might want to consult an NPC diviner before starting an adventure.

Specialist wizards have advantages and disadvantages when compared to mages. Their chance to know spells of their school of magic is greatly increased, but the intensive study results in a smaller chance to know spells outside their school. The number of spells they can cast increases, but they lose the ability to cast spells of the school in opposition to their specialty (opposite it in the diagram). Their ability to research and create new spells within their specialty is increased, but the initial selection of spells in their school may be quite limited. All in all, players must consider the advantages and disadvantages carefully.

Not all wizards can become specialists. The player character must meet certain requirements to become a specialist. Most specialist wizards must be single-classed; multi-classed characters cannot become specialists, except for gnomes, who seem to have more of a natural bent for the school of illusion than characters of any other race. Dual-class humans can choose to become specialists. The dedication to the particular school of magic requires all the attention and concentration of the character. He does not have time for other class-related pursuits.

In addition, each school has different restrictions on race, ability scores, and schools of magic allowed. These restrictions are given on Table 22. Note that lesser divination is not available as a specialty. The spells of this group, vital to the functioning of a wizard, are available to all wizards.

Race lists those races that, either through a natural tendency or a quirk of fate, are allowed to specialize in that art. Note that the gnome, though unable to be a regular mage, can specialize in illusions.

Minimum Ability Score lists the ability minimums needed to study intensively in that school. All schools require at least the minimum Intelligence demanded of a mage and an additional prime requisite, as listed.

Opposition School(s) always includes the school directly opposite the character's school of study in the diagram. In addition, the schools to either side of this one may also be disallowed due to the nature of the character's school. For example, an invoker/evoker cannot learn enchantment/charm or conjuration/summoning spells and cannot use magical items that duplicate spells from these schools.

Being a specialist does have significant advantages to balance the trade-offs the character must make. These are listed here:

A specialist gains one additional spell per spell level, provided the additional spell is taken in the specialist's school. Thus, a 1st-level illusionist could have two spells--one being any spell he knows and the other limited to spells of the illusion school.

Because specialists have an enhanced understanding of spells within their school, they receive a +1 bonus when making saving throws against those spells when cast by other wizards. Likewise, other characters suffer a -1 penalty when making saving throws against a specialist casting spells within his school. Both of these modifiers can be in effect at the same time--for example, when an enchanter casts an enchantment spell at another enchanter, the modifiers cancel each other out.

Specialists receive a bonus of +15% when learning spells from their school and a penalty of -15% when learning spells from other schools. The bonus or penalty is applied to the percentile dice roll the player must make when the character tries to learn a new spell (see Table 4).

Whenever a specialist reaches a new spell level, he automatically gains one spell of his school to add to his spell books. This spell can be selected by the DM or he can allow the player to pick. No roll for learning the spell need be made. It is assumed that the character has discovered this new spell during the course of his research and study.

When a specialist wizard attempts to create a new spell (using the rules given in the DMG), the DM should count the new spell as one level less (for determining the difficulty) if the spell falls within the school of the specialist. An enchanter attempting to create a new enchantment spell would have an easier time of it than an illusionist attempting to do the same.

Illusionist

Ability Requirements: Dexterity 16

Prime Requisite: Intelligence

Races Allowed: Human, Gnome

The illusionist is an example of a specialist. The description of the illusionist given here can be used as a guide for creating wizards specializing in other magical schools.

First, the school of illusion is a very demanding field of study. To specialize as an illusionist, a wizard needs a Dexterity score of at least 16.

An illusionist who has an Intelligence of 16 or more gains a 10% bonus to the experience points he earns.

Because the illusionist knows far more about illusions than the standard wizard, he is allowed a +1 bonus when rolling saving throws against illusions; other characters suffer a -1 penalty when rolling saving throws against his illusions. (These modifiers apply only if the spell allows a saving throw.)

Through the course of his studies, the illusionist has become adept at memorizing illusion spells (though it is still an arduous process). He can memorize an extra illusion spell at each spell level. Thus, as a 1st-level caster he can memorize two spells, although at least one of these must be an illusion spell.

Later, when he begins to research new spells for his collection, he finds it easier to devise new illusion spells to fill specialized needs. Research in other schools is harder and more time consuming for him.

Finally, the intense study of illusion magic prevents the character from mastering the other classes of spells that are totally alien to the illusion school (those diametrically opposite illusion on the diagram). Thus, the illusionist cannot learn spells from the schools of necromancy, invocation/evocation, or abjuration.

As an example, consider Joinville the illusionist. He has an Intelligence score of 15. In the course of his travels he captures an enemy wizard's spell book that contains an improved invisibility spell, a continual light spell, and a fireball spell, none of which are in Joinville's spell book. He has an 80% chance to learn the improved invisibility spell. Continual light is an alteration spell, however, so his chance to learn it is only 50% (consult Table 4 to see where these figures come from). He cannot learn the fireball spell, or even transcribe it into his spell book, because it is an evocation spell.

Priest

The priest is a believer and advocate of a god from a particular mythos. More than just a follower, he intercedes and acts on behalf of others, seeking to use his powers to advance the beliefs of his mythos.

All priests have certain powers: The ability to cast spells, the strength of arm to defend their beliefs, and special, deity-granted powers to aid them in their calling. While priests are not as fierce in combat as warriors, they are trained to use weaponry in the fight for their cause. They can cast spells, primarily to further their god's aims and protect its adherents. They have few offensive spells, but these are very powerful.

All priests use eight-sided Hit Dice (d8s). Only priests gain additional spells for having high Wisdom scores. All priests have a limited selection of weapons and armor, but the restrictions vary according to the mythos.

All priests use Table 23 to determine their advancement in level as they gain experience points. They also all use Table 24 to determine how many spells they receive at each level of experience.

All priests spells are divided into 16 categories called spheres of influence. Different types of priests have access to different spheres; no priest can cast spells from every sphere of influence. The 16 spheres of influence are as follows: All, Animal, Astral, Charm, Combat, Creation, Divination, Elemental, Guardian, Healing, Necromantic, Plant, Protection, Summoning, Sun, and Weather.

In addition, a priest has either major or minor access to a sphere. A priest with major access to a sphere can (eventually) cast all spells in the sphere. A priest with minor access to a sphere can cast only 1st-, 2nd-, and 3rd-level spells from that sphere.

All priests gain one eight-sided Hit Die (1d8) Per level from 1st through 9th. After 9th level, priests earn 2 hit points per level and they no longer gain additional hit point bonuses for high Constitution scores.

Table 23:

Priest Experience Levels

Hit Dice

Level Cleric Druid (d8)

1 0 0 1

2 1,500 2,000 2

3 3,000 4,000 3

4 6,000 7,500 4

5 13,000 12,500 5

6 27,500 20,000 6

7 55,000 35,000 7

8 110,000 60,000 8

9 225,000 90,000 9

10 450,000 125,000 9+2

11 675,000 200,000 9+4

12 900,000 300,000 9+6

13 1,125,000 750,000 9+8

14 1,350,000 1,500,000 9+10

15 1,575,000 3,000,000 9+12

16 1,800,000 3,500,000 9+14

17 2,025,000 500,000* 9+16

18 2,250,000 1,000,000 9+18

19 2,475,000 1,500,000 9+20

20 2,700,000 2,000,000 9+22

* See section on hierophant druids under "Druids" in this chapter.

Table 24:

Priest Spell Progression

Priest Spell Level

Level 1 2 3 4 5 6* 7**

1 1 -- -- -- -- -- --

2 2 -- -- -- -- -- --

3 2 1 -- -- -- -- --

4 3 2 -- -- -- -- --

5 3 3 1 -- -- -- --

6 3 3 2 -- -- -- --

7 3 3 2 1 -- -- --

8 3 3 3 2 -- -- --

9 4 4 3 2 1 -- --

10 4 4 3 3 2 -- --

11 5 4 4 3 2 1 --

12 6 5 5 3 2 2 --

13 6 6 6 4 2 2 --

14 6 6 6 5 3 2 1

15 6 6 6 6 4 2 1

16 7 7 7 6 4 3 1

17 7 7 7 7 5 3 2

18 8 8 8 8 6 4 2

19 9 9 8 8 6 4 2

20 9 9 9 8 7 5 2

* Usable only by priests with 17 or greater Wisdom.

** Usable only by priests with 18 or greater Wisdom.

Cleric

Ability Requirement: Wisdom 9

Prime Requisite: Wisdom

Races Allowed: All

The most common type of priest is the cleric. The cleric may be an adherent of any religion (though if the DM designs a specific mythos, the cleric's abilities and spells may be changed--see following). Clerics are generally good, but are not restricted to good; they can have any alignment acceptable to their order. A cleric must have a Wisdom score of 9 or more. High constitution and Charisma are also particularly useful.

A cleric who has a Wisdom of 16 or more gains a 10% bonus to the experience points he earns.

The cleric class is similar to certain religious orders of knighthood of the Middle Ages: the Teutonic Knights, the Knights Templars, and Hospitalers. These orders combined military and religious training with a code of protection and service. Memberswere trained as knights and devoted themselves to the service of the church. These orders were frequently found on the outer edges of the Christian world, either on the fringe of the wilderness or in war-torn lands. Archbishop Turpin (of The Song of Roland) is an example of such a cleric. Similar orders can also be found in other lands, such as the sohei of Japan.

Clerics are sturdy soldiers, although their selection of weapons is limited. They can wear any type of armor and use any shield. Standard clerics, being reluctant to shed blood or spread violence, are allowed to use only blunt, bludgeoning weapons. They can use a fair number of magical items including priest scrolls, most potions and rings, some wands and rods, staves, armor, shields, and magical versions of any weapons allowed by their order.

Spells are the main tools of the cleric, however, helping him to serve, fortify, protect, and revitalize those under his care. He has a wide variety of spells to choose from, suitable to many different purposes and needs. (A priest of a specific mythos probably has a more restricted range of spells.) A cleric has major access to every sphere of influence except the plant, animal, weather, and elemental spheres (he has minor access to the elemental sphere and cannot cast spells of the other three spheres).

The cleric receives his spells as insight directly from his deity (the deity does not need to make a personal appearance to grant the spells the cleric prays for), as a sign of and reward for his faith, so he must take care not to abuse his power lest it be taken away as punishment.

The cleric is also granted power over undead -- evil creatures that exist in a form of non-life, neither dead nor alive. The cleric is charged with defeating these mockeries of life. His ability to turn undead (see "Turning Undead" in Chapter 9: Combat) enables him to drive away these creatures or destroy them utterly (though a cleric of evil alignment can bind the creatures to his will). Some of the more common undead creatures are ghosts, zombies, skeletons, ghouls, and mummies. Vampires and liches (undead sorcerers) are two of the most powerful undead.

As a cleric advances in level, he gains additional spells, better combat skills, and a stronger turning ability. Upon reaching 8th level, the cleric automatically attracts a fanatically loyal group of believers, provided the character has established a place of worship of significant size. The cleric can build this place of worship at any time during his career, but he does not attract believers until he reaches 8th level. These followers are normal warriors, 0-level soldiers, ready to fight for the cleric's cause. The cleric attracts 20 to 200 of these followers; they arrive over a period of several weeks. After the initial followers assemble, no new followers trickle in to fill the ranks of those who have fallen in service. The DM decides the exact number and types of followers attracted by the cleric. The character can hire other troops as needed, but these are not as loyal as his followers.

At 9th level, the cleric may receive official approval to establish a religious stronghold, be it a fortified abbey or a secluded convent. Obviously, the stronghold must contain all the trappings of a place of worship and must be dedicated to the service of the cleric's cause. However, the construction cost of the stronghold is half the normal price, since the work has official sanction and much of the labor is donated. The cleric can hold property and build a stronghold any time before reaching 9th level, but this is done without church sanction and does not receive the benefits described above.

Priests of Specific Mythoi

In the simplest version of the AD&D game, clerics serve religions that can be generally described as "good" or "evil." Nothing more needs to be said about it; the game will play perfectly well at this level. However, a DM who has taken the time to create a detailed campaign world has often spent some of that time devising elaborate pantheons, either unique creations or adaptations from history or literature. If the option is open (and only your DM can decide), you may want your character to adhere to a particular mythos, taking advantage of the detail and color your DM has provided. If your character follows a particular mythos, expect him to have abilities, spells, and restrictions different from the generic cleric.

Priesthood in any mythos must be defined in five categories: requirements, weapons allowed, spells allowed, granted powers, and ethos.

Requirements

Before a character can become a priest of a particular mythos, certain requirements must be met. These usually involve minimum ability scores and mandatory alignments. All priests, regardless of mythos, must have Wisdom scores of at least 9. Beyond this, your DM can set other requirements as needed. A god of battle, for example, should require strong, healthy priests (13 Str, 12 Con). One whose sphere is art and beauty should demand high Wisdom and Charisma (16 or better). Most deities demand a specific type of behavior from their followers, and this will dictate alignment choices.

Weapons Allowed

Not all mythoi are opposed to the shedding of blood. Indeed, some require their priests to use swords, spears, or other specific weapons. A war deity might allow his priests to fight with spears or swords. An agricultural deity might emphasize weapons derived from farm implements -- sickles and bills, for example. A deity of peace and harmony might grant only the simplest and least harmful weapons -- perhaps only lassoes and nets. Given below are some suggested weapons, but many more are possible (the DM always has the final word in this matter).

Deity Weapon

Agriculture Bill, flail, sickle

Blacksmith War hammer

Death Sickle

Disease Scourge, whip

Earth Pick

Healing Man-catcher, quarterstaff

Hunt Bow and arrows, javelin, light lance, sling, spear

Lightning Dart, javelin, spear

Love Bow and arrows, man-catcher

Nature Club, scimitar, sickle

Oceans Harpoon, spear, trident

Peace Quarterstaff

Strength Hammer

Thunder Club, mace, war hammer

War Battle axe, mace, morning star, spear, sword

Wind Blowgun, dart

Of course there are many other reasons a deity might be associated with a particular weapon or group of weapons. These are often cultural, reflecting the weapons used by the people of the area. There may be a particular legend associated with the deity, tying it to some powerful artifact weapon (Thor's hammer, for example). The DM has the final choice in all situations.

Spells Allowed

A priest of a particular mythos is allowed to cast the spells from only a few, related spheres. The priest's deity will have major and minor accesses to certain spheres, and this determines the spells available to the priest. (Each deity's access to spheres is determined by the DM as he creates the pantheon of his world.) The 16 spheres of influence are defined in the following paragraphs.

A priest whose deity grants major access to a sphere can choose from any spell within that sphere (provided he is high enough in level to cast it), while one allowed only minor access to the sphere is limited to spells of 3rd level or below in that sphere. The combination of major and minor accesses to spheres results in a wide variation in the spells available to priests who worship different deities.

All refers to spells usable by any priest, regardless of mythos. There are no Powers (deities) of the Sphere of All. This group includes spells the priest needs to perform basic functions.

Animal spells are those that affect or alter creatures. It does not include spells that affect people. Deities of nature and husbandry typically operate in this sphere.

Astral is a small sphere of spells that enable movement or communication between the different planes of existence. The masters of a plane or particularly meddlesome powers often grant spells from this sphere.

Charm spells are those that affect the attitudes and actions of people. Deities of love, beauty, trickery, and art often allow access to this sphere.

Combat spells are those that can be used to directly attack or harm the enemies of the priest or his mythos. These are often granted by deities of war or death.

Creation spells enable the priest to produce something from nothing, often to benefit his followers. This sphere can fill many different roles, from a provider to a trickster.

Divination enables the priest to learn the safest course of action in a particular situation, find a hidden item, or recover long-forgotten information. Deities of wisdom and knowledge typically have access to this sphere.

Elemental spells are all those that affect the four basic elements of creation--earth, air, fire, and water. Nature deities, elemental deities, those representing or protecting various crafts, and the deities of sailors would all draw spells from this sphere.

Guardian spells place magical sentries over an item or person. These spells are more active than protection spells because they create an actual guardian creature of some type. Protective, healing, and trickster deities may all grant spells of this sphere.

Healing spells are those that cure diseases, remove afflictions, or heal wounds. These spells cannot restore life or regrow lost limbs. Healing spells can be reversed to cause injury, but such use is restricted to evil priests. Protective and merciful deities are most likely to grant these spells, while nature deities may have lesser access to them.

Necromantic spells restore to a creature some element of its life-force that has been totally destroyed. It might be life, a limb, or an experience level. These spells in reverse are powerfully destructive, and are used only by extremely evil priests. Deities of life or death are most likely to act in this sphere.

Plant spells affect plants, ranging from simple agriculture (improving crops and the like) to communicating with plant-like creatures. Agricultural and nature Powers grant spells in this sphere.

Protection spells create mystical shields to defend the priest or his charges from evil attacks. War and protective deities are most likely to use these, although one devoted to mercy and kindness might also bestow these spells.

Summoning spells serve to call creatures from other places, or even other dimensions, to the service of the priest. Such service is often against the will of the creature, so casting these spells often involves great risk. Since creatures summoned often cause great harm and destruction, these spells are sometimes bestowed by war or death powers.

Sun spells are those dealing in the basic powers of the solar universe--the purity of light and its counterpart darkness. Sun spells are very common with nature, agricultural, or life-giving powers.

Weather spells enable the priest to manipulate the forces of weather. Such manipulation can be as simple as providing rain to parched fields, or as complex as unbridling the power of a raging tempest. Not surprisingly, these tend to be the province of nature and agricultural powers and appear in the repertoire of sea and ocean powers.

Additional spheres can be created by your DM. The listed spheres are typical of the areas in which deities concentrate their interest and power. Spells outside the deity's major and minor spheres of influence are not available to its priests.

Furthermore, the priest can obtain his spells at a faster or slower pace than the normal cleric. Should the character's ethos place emphasis on self-reliance, the spell progression is slower. Those deities associated with many amazing and wondrous events might grant more spells per level. Of course, your DM has final say on this, and he must balance the gain or loss of spells against the other powers, abilities, and restrictions of the character.

Granted Powers

Another aspect of a specific mythos is the special powers available to its priests. The cleric's granted power is the ability to turn undead. This ability, however, is not common to all priests. Other deities grant powers in accordance with their spheres. If your DM is using a specific mythos, he must decide what power is granted to your priest. Some possible suggestions are given below.

*Incite Berserker Rage, adding a +2 bonus to attack and damage rolls (War).

*Soothing Word, able to remove fear and influence hostile reactions (Peace, Mercy, Healing).

*Charm or Fascination, which could act as a suggestion spell (Love, Beauty, Art).

*Inspire Fear, radiating an aura of fear similar to the fear spell (Death).

These are only a few of the granted powers that might be available to a character. As with allowed weapons, much depends on the culture of the region and the tales and legends surrounding the Power and its priests.

Ethos

All priests must live by certain tenets and beliefs. These guide the priests' behavior. Clerics generally try to avoid shedding blood and try to aid their community. A war deity may order its priests to be at the forefront of battles and to actively crusade against all enemies. A harvest deity may want its priests to be active in the fields. The ethos may also dictate what alignment the priest must be. The nature of the mythos helps define the strictures the priest must follow.

Priest Titles

Priests of differing mythoi often go by titles and names other than priest. A priest of nature, for example (especially one based on Western European tradition) could be called a druid (see below). Shamans and witch doctors are also possibilities. A little library research will turn up many more unique and colorful titles, a few of which are listed here:

Abbess, Abbot, Ayatollah, Bonze, Brother, Dom, Eye of the Law, Friar, Guru, Hajji, Imam, Mendicant, Metropolitan, Mullah, Pardoner, Patriarch, Prelate, Prior, Qadi, Rector, Vicar, and Yogi

Balancing It All

When creating a priest of a specific mythos, careful attention must be given to the balance of the character's different abilities. A priest strong in one area or having a wide range of choice must be appropriately weakened in another area so that he does not become too powerful compared to the other priests in the game. If a war deity allows a priest the use of all weapons and armor, the character should be limited in the spells allowed or powers granted. At the other extreme, a character who follows a deity of peace should have significant spells and granted powers to make up for his extremely limited or non-existent choice of weapons. A druid, for example, has more granted powers than a normal cleric to compensate for his limited armor and spell selection.

Druid

Ability Requirements: Wisdom 12

Charisma 15

Prime Requisites: Wisdom, Charisma

Races Allowed: Human, Half-elf

Historically, druids lived among the Germanic tribes of Western Europe and Britain during the days of the Roman Empire. They acted as advisors to chieftains and held great influence over the tribesmen. Central to their thinking was the belief that the earth was the mother and source of all life. They revered many natural things -- the sun, moon, and certain trees -- as deities. Druids in the AD&D game, however, are only loosely patterned after these historical figures. They are not required to behave like or follow the beliefs of historical druids.

The druid is an example of a priest designed for a specific mythos. His powers and beliefs are different from those of the cleric. The druid is a priest of nature and guardian of the wilderness, be it forest, plains, or jungle.

Requirements

A druid must be human or half-elven. He must have a Wisdom score of at least 12 and a Charisma score of 15 or more. Both of these abilities are prime requisites.

Weapons Allowed

Unlike the cleric, the druid is allowed to use only "natural" armors -- padded, hide, or leather armor and wooden shields, including those with magical enhancements. All other armors are forbidden to him. His weapons are limited to club, sickle, dart, spear, dagger, scimitar, sling, and staff.

Spells Allowed

Druids do not have the same range of spells as clerics. They have major access to the following spheres: all, animal, elemental, healing, plant, and weather. They have minor access to the divination sphere. Druids can use all magical items normally allowed priests, except for those that are written (books and scrolls) and armor and weapons not normally allowed for druids.

Granted Powers

A druid makes most saving throws as a priest, but he gains a bonus of +2 to all saving throws vs. fire or electrical attacks.

All druids can speak a secret language in addition to any other tongues they know. (If the optional proficiency rules are used, this language does not use a proficiency slot.) The vocabulary of this druidic language is limited to dealing with nature and natural events. Druids jealously guard this language; it is the one infallible method they have of recognizing each other.

Additional powers are granted as the druid reaches higher levels:

He can identify plants, animals, and pure water with perfect accuracy after he reaches 3rd level.

He can pass through overgrown areas (thick thorn bushes, tangled vines, briar patches, etc.) without leaving a trail and at his normal movement rate after he reaches 3rd level.

He can learn the languages of woodland creatures. These include centaurs, dryads, elves, fauns, gnomes, dragons, giants, lizard men, manticores, nixies, pixies, sprites, and treants. The druid can add one language at 3rd level and one more every time he advances a level above 3rd. (If the optional proficiency rules are used, it is the druid's choice whether or not to spend a proficiency slot on one or more of these languages.)

He is immune to charm spells cast by woodland creatures (dryads, nixies, etc.) after he reaches 7th level.

He gains the ability to shapechange into a reptile, bird, or mammal up to three times per day after he reaches 7th level. Each animal form (reptile, bird, or mammal) can be used only once per day. The size can vary from that of a bullfrog or small bird to as large as a black bear. Upon assuming a new form, the druid heals 10-60% (1d6 × 10%) of all damage he has suffered (round fractions down). The druid can only assume the form of a normal (real world) animal in its normal proportions, but by doing so he takes on all of that creature's characteristics -- its movement rate and abilities, its Armor Class, number of attacks, and damage per attack.

Thus, a druid could change into a wren to fly across a river, transform into a black bear on the opposite side and attack the orcs gathered there, and finally change into a snake to escape into the bushes before more orcs arrive.

The druid's clothing and one item held in each hand also become part of the new body; these reappear when the druid resumes his normal shape. The items cannot be used while the druid is in animal form.

A druid cannot turn undead.

Ethos

As protectors of nature, druids are aloof from the complications of the temporal world. Their greatest concern is for the continuation of the orderly and proper cycles of nature--birth, growth, death, and rebirth. Druids tend to view all things as cyclic and thus, the battles of good and evil are only the rising and falling tides of time. Only when the cycle and balance are disrupted does the druid become concerned. Given this view of things, the druid must be neutral in alignment.

Druids are charged with protecting wilderness--in particular trees, wild plants, wild animals, and crops. By association, they are also responsible for their followers and their animals. Druids recognize that all creatures (including humans) need food, shelter, and protection from harm. Hunting, farming, and cutting lumber for homes are logical and necessary parts of the natural cycle. However, druids do not tolerate unnecessary destruction or exploitation of nature for profit. Druids often prefer subtle and devious methods of revenge against those who defile nature. It is well known that druids are both very unforgiving and very patient.

Mistletoe is an important holy symbol to druids and it is a necessary part of some spells (those requiring a holy symbol). To be fully effective, the mistletoe must be gathered by the light of the full moon using a golden or silver sickle specially made for the purpose. Mistletoe gathered by other means halves the effectiveness of a given spell, if it causes damage or has an area of effect, and grants the target a +2 bonus to his saving throw if a saving throw is applicable.

Druids as a class do not dwell permanently in castles, cities, or towns. All druids prefer to live in sacred groves, where they build small sod, log, or stone cottages.

Druid Organization

Druids have a worldwide structure. At their upper levels (12th and above), only a few druids can hold each level.

Druids, Archdruids, and the Great Druid

At 12th level, the druid character acquires the official title of "druid" (all druid characters below 12th level are officially known as "initiates"). There can be only nine 12th-level druids in any geographic region (as defined by oceans, seas, and mountain ranges; a continent may consist of three or four such regions). A character cannot reach 12th level unless he takes his place as one of the nine druids. This is possible only if there are currently fewer than nine druids in the region, or if the character defeats one of the nine druids in magical or hand-to-hand combat, thereby assuming the defeated druid's position. If such combat is not mortal, the loser drops experience points so that he has exactly 200,000 remaining--just enough to be 11th level.

The precise details of each combat are worked out between the two combatants in advance. The combat can be magical, non-magical, or a mixture of both. It can be fought to the death, until only one character is unconscious, until a predetermined number of hit points is lost, or even until the first blow is landed, although in this case both players would have to be supremely confident of their abilities. Whatever can be agreed upon between the characters is legitimate, so long as there is some element of skill and risk.

When a character becomes a 12th-level druid, he gains three underlings. Their level depends on the character's position among the nine druids. The druid with the most experience points is served by three initiates of 9th level; the second-most experienced druid is served by three initiates of 8th level; and so on, until the least experienced druid is served by three 1st-level initiates.