This section is intended for novice role-players. If you have played role-playing games before, don't be surprised if what you read here sounds familiar.

Games come in a wide assortment of types: board games, card games, word games, picture games, miniatures games. Even within these categories are subcategories. Board games, for example, can be divided into path games, real estate games, military simulation games, abstract strategy games, mystery games, and a host of others.

Still, in all this mass of games, role-playing games are unique. They form a category all their own that doesn't overlap any other category.

For that reason, role-playing games are hard to describe. Comparisons don't work because there isn't anything similar to compare them to. At least, not without stretching your imagination well beyond its normal, everyday extension.

But then, stretching your imagination is what role-playing is all about. So let's try an analogy.

Imagine that you are playing a simple board game, called Snakes and Ladders. Your goal is to get from the bottom to the top of the board before all the other players. Along the way are traps that can send you sliding back toward your starting position. There are also ladders that can let you jump ahead, closer to the finish space. So far, it's pretty simple and pretty standard.

Now let's change a few things. Instead of a flat, featureless board with a path winding from side to side, let's have a maze. You are standing at the entrance, and you know that there's an exit somewhere, but you don't know where. You have to find it.

Instead of snakes and ladders, we'll put in hidden doors and secret passages. Don't roll a die to see how far you move; you can move as far as you want. Move down the corridor to the intersection. You can turn right, or left, or go straight ahead, or go back the way you came. Or, as long as you're here, you can look for a hidden door. If you find one, it will open into another stretch of corridor. That corridor might take you straight to the exit or lead you into a blind alley. The only way to find out is to step in and start walking.

Of course, given enough time, eventually you'll find the exit. To keep the game interesting, let's put some other things in the maze with you. Nasty things. Things like vampire bats and hobgoblins and zombies and ogres. Of course, we'll give you a sword and a shield, so if you meet one of these things you can defend yourself. You do know how to use a sword, don't you?

And there are other players in the maze as well. They have swords and shields, too. How do you suppose another player would react if you chance to meet? He might attack, but he also might offer to team up. After all, even an ogre might think twice about attacking two people carrying sharp swords and stout shields.

Finally, let's put the board somewhere you can't see it. Let's give it to one of the players and make that player the referee. Instead of looking at the board, you listen to the referee as he describes what you can see from your position on the board. You tell the referee what you want to do and he moves your piece accordingly. As the referee describes your surroundings, try to picture them mentally. Close your eyes and construct the walls of the maze around yourself. Imagine the hobgoblin as the referee describes it whooping and gamboling down the corridor toward you. Now imagine how you would react in that situation and tell the referee what you are going to do about it.

We have just constructed a simple role-playing game. It is not a sophisticated game, but it has the essential element that makes a role-playing game: The player is placed in the midst of an unknown or dangerous situation created by a referee and must work his way through it.

This is the heart of role-playing. The player adopts the role of a character and then guides that character through an adventure. The player makes decisions, interacts with other characters and players, and, essentially, "pretends" to be his character during the course of the game. That doesn't mean that the player must jump up and down, dash around, and act like his character. It means that whenever the character is called on to do something or make a decision, the player pretends that he is in that situation and chooses an appropriate course of action.

Physically, the players and referee (the DM) should be seated comfortably around a table with the referee at the head. Players need plenty of room for papers, pencils, dice, rule books, drinks, and snacks. The referee needs extra space for his maps, dice, rule books, and assorted notes.

The Goal

Another major difference between role-playing games and other games is the ultimate goal. Everyone assumes that a game must have a beginning and an end and that the end comes when someone wins. That doesn't apply to role-playing because no one "wins" in a role-playing game. The point of playing is not to win but to have fun and to socialize.

An adventure usually has a goal of some sort: protect the villagers from the monsters; rescue the lost princess; explore the ancient ruins. Typically, this goal can be attained in a reasonable playing time: four to eight hours is standard. This might require the players to get together for one, two, or even three playing sessions to reach their goal and complete the adventure.

But the game doesn't end when an adventure is finished. The same characters can go on to new adventures. Such a series of adventures is called a campaign.

Remember, the point of an adventure is not to win but to have fun while working toward a common goal. But the length of any particular adventure need not impose an artificial limit on the length of the game. The AD&D game embraces more than enough adventure to keep a group of characters occupied for years.

Required Materials

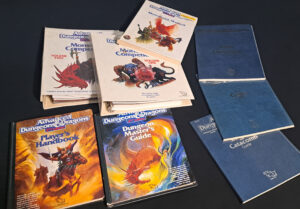

Aside from a copy of this book, very little is needed to play the AD&D game.

You will need some sort of character record. TSR publishes character record sheets that are quite handy and easy to use, but any sheet of paper will do. Blank paper, lined paper, or even graph paper can be used. A double-sized sheet of paper (11 × 17 inches), folded in half, is excellent. Keep your character record in pencil, because it will change frequently during the game. A good eraser is also a must.

A full set of polyhedral dice is necessary. A full set consists of 4-, 6-, 8-, 10-, 12-, and 20-sided dice. A few extra 6- and 10-sided dice are a good idea. Polyhedral dice should be available wherever you got this book.

Throughout these rules, the various dice are referred to by a code that is in the form: # of dice, followed by "d," followed by a numeral for the type of dice. In other words, if you are to roll one 6-sided die, you would see "roll 1d6." Five 12-sided dice are referred to as "5d12." (If you don't have five 12-sided dice, just roll one five times and add the results.)

When the rules say to roll "percentile dice" or "d100," you need to generate a random number from 1 to 100. One way to do this is to roll two 10-sided dice of different colors. Before you roll, designate one die as the tens place and the other as the ones place. Rolling them together enables you to generate a number from 1 to 100 (a result of "0" on both dice is read as "00" or "100"). For example, if the blue die (representing the tens place) rolls an "8" and the red die (ones place) rolls a "5," the result is 85. Another, more expensive, way to generate a number from 1 to 100 is to buy one of the dice that actually have numbers from 1 to 100 on them.

At least one player should have a few sheets of graph paper for mapping the group's progress. Assorted pieces of scratch paper are handy for making quick notes, for passing secret messages to other players or the DM, or for keeping track of odd bits of information that you don't want cluttering up your character record.

Miniature figures are handy for keeping track of where everyone is in a confusing situation like a battle. These can be as elaborate or simple as you like. Some players use miniature lead or pewter figures painted to resemble their characters. Plastic soldiers, chess pieces, boardgame pawns, dice, or bits of paper can work just as well.

An Example of Play

To further clarify what really goes on during an AD&D game, read the following example. This is typical of the sort of action that occurs during a playing session.

Shortly before this example begins, three player characters fought a skirmish with a wererat (a creature similar to a werewolf but which becomes an enormous rat instead of a wolf). The wererat was wounded and fled down a tunnel. The characters are in pursuit. The group includes two fighters and a cleric. Fighter 1 is the group's leader.

DM: You've been following this tunnel for about 120 yards. The water on the floor is ankle deep and very cold. Now and then you feel something brush against your foot. The smell of decay is getting stronger. The tunnel is gradually filling with a cold mist.

Fighter 1: I don't like this at all. Can we see anything up ahead that looks like a doorway, or a branch in the tunnel?

DM: Within the range of your torchlight, the tunnel is more or less straight. You don't see any branches or doorways.

Cleric: The wererat we hit had to come this way. There's nowhere else to go.

Fighter 1: Unless we missed a hidden door along the way. I hate this place; it gives me the creeps.

Fighter 2: We have to track down that wererat. I say we keep going.

Fighter 1: OK. We keep moving down the tunnel. But keep your eyes open for anything that might be a door.

DM: Another 30 or 35 yards down the tunnel, you find a stone block on the floor.

Fighter 1: A block? I take a closer look.

DM: It's a cut block, about 12 by 16 inches, and 18 inches or so high. It looks like a different kind of rock than the rest of the tunnel.

Fighter 2: Where is it? Is it in the center of the tunnel or off to the side?

DM: It's right up against the side.

Fighter 1: Can I move it?

DM (checking the character's Strength score): Yeah, you can push it around without too much trouble.

Fighter 1: Hmmm. This is obviously a marker of some sort. I want to check this area for secret doors. Spread out and examine the walls.

DM (rolls several dice behind his rule book, where players can't see the results): Nobody finds anything unusual along the walls.

Fighter 1: It has to be here somewhere. What about the ceiling?

DM: You can't reach the ceiling. It's about a foot beyond your reach.

Cleric: Of course! That block isn't a marker, it's a step. I climb up on the block and start prodding the ceiling.

DM (rolling a few more dice): You poke around for 20 seconds or so, then suddenly part of the tunnel roof shifts. You've found a panel that lifts away.

Fighter 1: Open it very carefully.

Cleric: I pop it up a few inches and push it aside slowly. Can I see anything?

DM: Your head is still below the level of the opening, but you see some dim light from one side.

Fighter 1: We boost him up so he can get a better look.

DM: OK, your friends boost you up into the room . . .

Fighter 1: No, no! We boost him just high enough to get his head through the opening.

DM: OK, you boost him up a foot. The two of you are each holding one of his legs. Cleric, you see another tunnel, pretty much like the one you were in, but it only goes off in one direction. Thee's a doorway about 10 yards away with a soft light inside. A line of muddy pawprints leads from the hole you're in to the doorway.

Cleric: Fine. I want the fighters to go first.

DM: As they're lowering you back to the block, everyone hears some grunts, splashing, and clanking weapons coming from further down the lower tunnel. They seem to be closing fast.

Cleric: Up! Up! Push me back up through the hole! I grab the ledge and haul myself up. I'll help pull the next guy up.

(All three characters scramble up through the hole.)

DM: What about the panel?

Fighter 1: We push it back into place.

DM: It slides back into its slot with a nice, loud "clunk." The grunting from below gets a lot louder.

Fighter 1: Great, they heard it. Cleric, get over here and stand on this panel. We're going to check out that doorway.

DM: Cleric, you hear some shouting and shuffling around below you, then there's a thump and the panel you're standing on lurches.

Cleric: They're trying to batter it open!

DM (to the fighters): When you peer around the doorway, you see a small, dirty room with a small cot, a table, and a couple of stools. On the cot is a wererat curled up into a ball. Its back is toward you. There's another door in the far wall and a small gong in the corner.

Fighter 1: Is the wererat moving?

DM: Not a bit. Cleric, the panel just thumped again. You can see a little crack in it now.

Cleric: Do something quick, you guys. When this panel starts coming apart, I'm getting off it.

Fighter 1: OK already! I step into the room and prod the wererat with my shield. What happens?

DM: Nothing. You see blood on the cot.

Fighter 1: Is this the same wererat we fought before?

DM: Who knows? All wererats look the same to you. Cleric, the panel thumps again. That crack is looking really big.

Cleric: That's it. I get off the panel, I'm moving into the room with everybody else.

DM: There's a tremendous smash and you hear chunks of rock banging around out in the corridor, followed by lots of snarling and squeaking. You see flashes of torchlight and wererat shadows through the doorway.

Fighter 1: All right, the other fighter and I move up to block the doorway. That's the narrowest area, they can only come through it one or two at a time. Cleric, you stay in the room and be ready with your spells.

Fighter 2: At last, a decent, stand-up fight!

DM: As the first wererat appears in the doorway with a spear in his paws, you hear a slam behind you.

Cleric: I spin around. What is it?

DM: The door in the back of the room is broken off its hinges. Standing in the doorway, holding a mace in each paw, is the biggest, ugliest wererat you've ever seen. A couple more pairs of red eyes are shining through the darkness behind him. He's licking his chops in a way that you find very unsettling.

Cleric: Aaaaarrrgh! I scream the name of my deity at the top of my lungs and then flip over the cot with the dead wererat on it so the body lands in front of him. I've got to have some help here, guys.

Fighter 1 (to fighter 2): Help him, I'll handle this end of the room. (To DM:) I'm attacking the wererat in the first doorway.

DM: While fighter 2 is switching positions, the big wererat looks at the body on the floor and his jaw drops. He looks back up and says, "That's Ignatz. He was my brother. You killed my brother." Then he raises both maces and leaps at you.

At this point a ferocious melee breaks out. The DM uses the combat rules to play out the battle. If the characters survive, they can continue on whatever course they choose.